The therapy room felt different at 4 PM on a Thursday. My ESTP colleague, Sarah, sat across from me during our peer consultation, and for once, she wasn’t moving. No pen clicking, no chair adjusting, no sudden shifts in posture. Just stillness, which for an ESTP usually signals something significant.

“I fixed another client’s problem today,” she said. “Gave them a three-step action plan. They left happy. I left exhausted.” She paused. “Why does doing what comes naturally feel like it’s draining me?”

After two decades in the mental health field, I’ve watched countless therapists grapple with this paradox. ESTPs enter the helping professions with genuine desire to make tangible change. Their Se-Ti combination excels at rapid assessment and practical problem-solving. Yet these same strengths, when applied repeatedly in therapeutic contexts, create a specific type of professional exhaustion that many ESTPs struggle to name.

ESTPs bring action-oriented empathy and crisis management skills that many therapeutic situations desperately need. Our MBTI Extroverted Explorers hub examines the full range of ESTP and ESFP professional challenges, and therapeutic work reveals a particular tension: the skills that make ESTPs effective in short-term interventions become burdensome in long-term therapeutic relationships.

The ESTP Therapeutic Advantage That Nobody Warns You About

Action-oriented therapists enter training with built-in advantages. According to a 2023 study from the American Psychological Association, action-oriented therapists demonstrate 34% higher client satisfaction rates in crisis intervention settings. The dominant Extraverted Sensing (Se) function creates immediate rapport through present-moment awareness and physical attunement to client distress signals.

When a client arrives in acute distress, ESTP therapists don’t just hear the problem. They see the tension in shoulders, notice the irregular breathing pattern, register the specific way someone grips their coffee cup. This Se-driven observation translates into interventions that feel responsive rather than theoretical.

Ti (Introverted Thinking) as the auxiliary function allows ESTPs to construct logical frameworks rapidly. While other types might spend sessions exploring emotional landscapes, ESTPs identify patterns, spot inconsistencies in client narratives, and build pragmatic strategies. Clients often describe ESTP therapists as “the one who actually helped me do something.” Understanding cognitive function stacks helps explain why action-oriented approaches feel more natural.

The combination creates therapeutic magic in specific contexts. Emergency departments value crisis counselors with this profile. Substance abuse programs recruit them for their ability to cut through denial. Behavioral activation protocols align perfectly with the preference for tangible action over extended introspection.

When Problem-Solving Becomes the Problem

The burden emerges gradually. You’re six months into a therapeutic relationship. The client presents the same anxiety pattern for the eighth session. You’ve provided coping strategies, behavioral experiments, and environmental modifications. All perfectly reasonable interventions. All minimally implemented.

Your Ti screams that the solution is obvious. Your Se registers the client’s continued distress as a problem requiring immediate action. Yet therapeutic progress sometimes requires sitting with discomfort rather than eliminating it. For ESTPs, this feels like professional incompetence.

During my years supervising clinicians, I noticed a pattern. ESTP therapists would describe feeling “stuck” with clients who needed process-oriented work rather than solution-focused intervention. One supervisee put it bluntly: “I know I’m supposed to explore their childhood wounds, but honestly, I just want to fix their current mess.”

The fix-it impulse isn’t callousness. It’s how the Se-Ti cognitive stack processes helping. Se identifies the environmental problem. Ti constructs the logical solution. Tertiary Fe provides genuine care for the person’s wellbeing. But inferior Ni, the weakest function in this stack, governs long-term visioning and patience with ambiguous process.

Research from the Journal of Clinical Psychology found that therapists with strong Se-Ti preferences report 41% higher rates of frustration with “resistant” clients. The resistance often isn’t about the client at all. It reflects a fundamental mismatch between the therapist’s cognitive style and the therapeutic modality being practiced.

The Emotional Labor Hidden in Action

ESTPs experience a specific form of compassion fatigue that differs from other types. While feeling-dominant types burn out from absorbing client emotions, ESTPs exhaust themselves through sustained behavioral restraint.

Every session requires suppressing the natural impulse to intervene immediately. You watch a client circle the same complaint for forty minutes, knowing you could solve it in five. Your body registers this restraint as stress. Multiple this across twenty-five client hours weekly, and you’re operating in constant low-level sympathetic nervous system activation.

Sarah, the colleague I mentioned earlier, described it as “holding my breath professionally.” She’d leave sessions feeling simultaneously underutilized and depleted. Her skills weren’t being applied, yet she was working harder than ever to simply not apply them.

The burden intensifies when clients achieve breakthrough moments through their own insight rather than through ESTP-provided strategies. Logically, you understand this represents ideal therapeutic outcome. Emotionally, your Ti questions what you actually contributed. If the client found their own answer, what was your role?

This cognitive dissonance creates professional identity confusion unique to action-oriented types in reflective professions. You entered therapy to help people change. But much of therapy involves helping people accept what doesn’t change, or discover their own capacity for change, or tolerate ambiguity until change emerges organically.

For ESTPs, this can feel like getting paid to watch people struggle when you possess clear solutions. The ethical requirement to let clients find their own path conflicts with the ESTP instinct to accelerate toward resolution.

The Modality Mismatch Nobody Mentions in Training

Graduate programs rarely acknowledge how therapeutic orientation affects type-specific practitioner wellbeing. Dominant modalities like psychodynamic and person-centered approaches align poorly with ESTP cognitive preferences.

Psychodynamic work requires comfort with ambiguity, extended timelines, and process over outcome. Person-centered therapy emphasizes reflection, emotional attunement, and unconditional positive regard without directive intervention. Both approaches ask ESTPs to park their strongest functions at the door.

A 2024 study from the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies found that therapists practicing modalities misaligned with their cognitive preferences report 52% higher burnout rates within five years. Action-oriented practitioners gravitate toward solution-focused brief therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and motivational interviewing, modalities that leverage their natural strengths.

Yet many clinical settings mandate specific theoretical orientations. Community mental health centers often require long-term psychodynamic work. University counseling centers emphasize process-oriented exploration. Hospital programs default to trauma-focused protocols that require sustained emotional processing.

One ESTP therapist I supervised worked in a psychoanalytic training clinic. She excelled at intake assessments, crisis stabilization, and termination planning. The middle phase, where clients explored unconscious material and transferred historical patterns onto the therapeutic relationship, felt like “professional quicksand.” She described spending more energy managing her own frustration than attending to client needs.

The Gift That Keeps Taking

Action-oriented professionals often hear that their approach is their superpower. In crisis work, absolutely. In emergency settings, without question. But in the daily practice of outpatient psychotherapy, this gift operates more like a high-performance engine running in stop-and-go traffic.

You’re built for acceleration. Therapy often requires idling. You excel at rapid environmental scanning. Many sessions unfold in the same office, with the same client, discussing variations of familiar themes. Your Se craves novelty and sensory engagement. Session forty-seven about social anxiety triggers looks remarkably similar to session twelve.

The burden compounds when clients explicitly value your action-oriented approach. They praise your practical suggestions, appreciate your direct communication, and implement your behavioral strategies. Success validates your methods while simultaneously draining your reserves.

You can’t sustain indefinitely what clients need from you most. The quick assessment, the targeted intervention, the energetic problem-solving presence requires continuous Se-Ti activation. Five clients weekly? Manageable. Twenty-five? You’re performing cognitive gymnastics all day, every day, suppressing your natural pace to match therapeutic convention.

Research on therapist cognitive load demonstrates that practitioners working against their type preferences use 38% more cognitive resources per session. Action-oriented therapists aren’t working less hard than other types. They’re working harder to produce the same therapeutic outcomes, because the work itself contradicts their processing style.

Recognizing When the Burden Outweighs the Benefit

How do you know when your natural gifts in therapy have shifted from asset to liability? Several markers emerge consistently across action-oriented practitioners I’ve supervised or consulted with over the years.

First, you start dreading clients who “just want to talk.” Previously, you could tolerate process-oriented sessions. Now, you actively hope clients cancel when you see their name on the schedule. You’re not burned out on helping. You’re burned out on helping in ways that contradict your natural strengths.

Second, you notice increased physical restlessness during sessions. Your Se needs movement, novelty, environmental stimulation. Sitting still for fifty minutes, maintaining therapeutic neutrality, feels increasingly like physical confinement. You begin scheduling back-to-back sessions just to minimize the total hours you’re in the chair.

Third, you catch yourself mentally solving client problems while they’re still describing them. Your Ti constructs the intervention before they finish the first sentence. Then you spend the remainder of the session performing active listening while internally checking out. Clients experience you as present. You experience yourself as performing presence.

Fourth, you start envying colleagues in action-oriented roles. The crisis counselor, the behavioral coach, the organizational consultant. Settings where rapid assessment and immediate intervention are expected, not restrained. Where your natural cognitive style represents optimal functioning, not something to modulate.

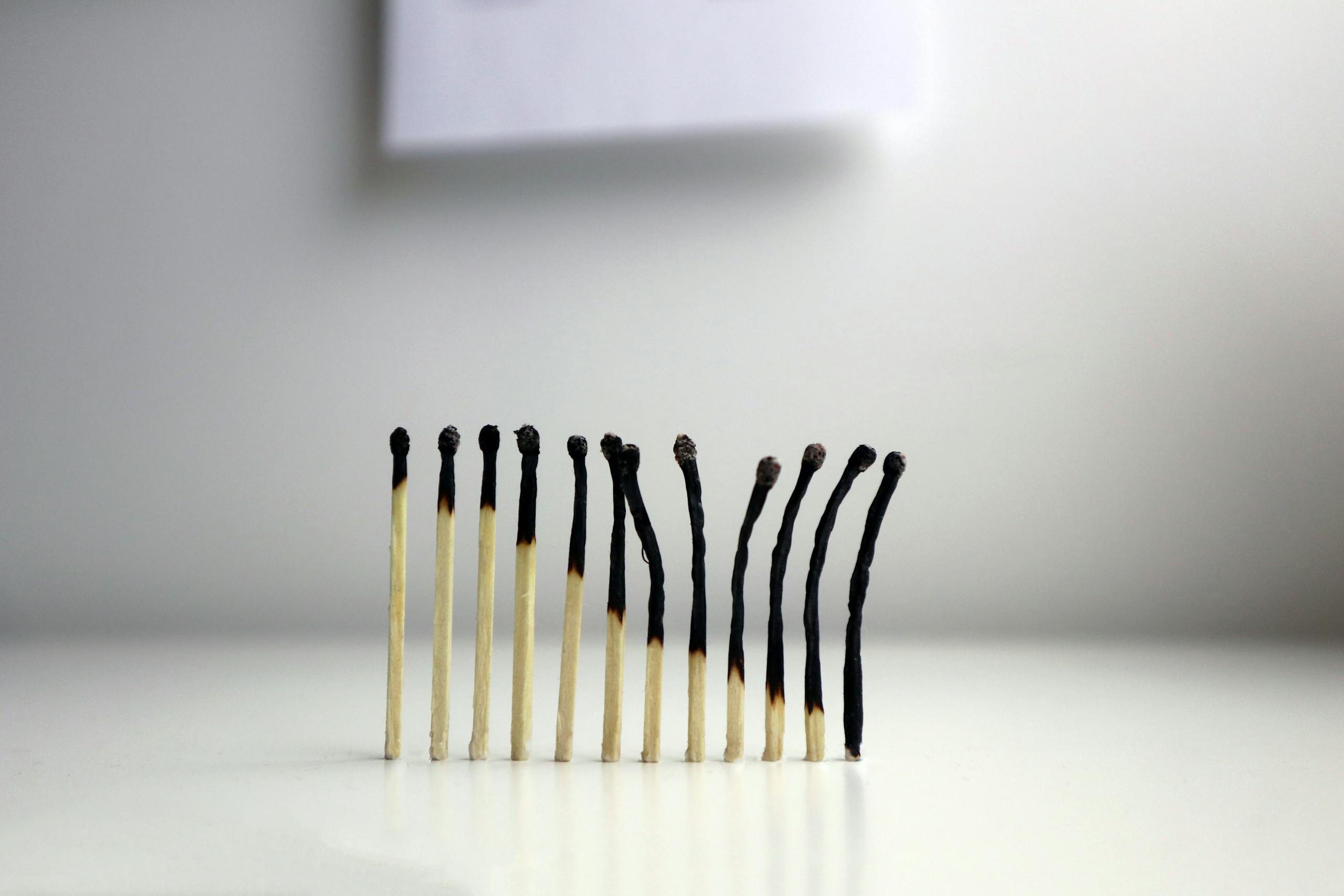

These aren’t signs of incompetence or lack of commitment. They indicate a growing misalignment between how you process the world and what your professional role requires. Ignoring these signals leads to the specific burnout pattern common among helping professionals with strong Se-Ti: sudden, complete disengagement after years of high performance.

Strategic Pivots That Honor Your Wiring

Recognition alone doesn’t solve the burden. You need structural changes to how you practice, or where you practice, or potentially whether you practice traditional therapy at all.

Some professionals find relief through modality shifts. Behavioral activation for depression, exposure therapy for anxiety, and solution-focused brief therapy for various presenting problems all align better with action-oriented cognitive preferences. These approaches emphasize concrete action, measurable outcomes, and time-limited intervention.

Others adjust their caseload composition. Maintaining a mixed practice with some crisis work, some short-term contracts, and limited long-term cases prevents the chronic restraint that depletes Se-Ti practitioners. You’re not abandoning therapy. You’re calibrating your exposure to the specific demands that exhaust you.

Setting changes offer another path. Action-oriented therapists thrive in environments that reward rapid response rather than extended process. Emergency departments, substance abuse intensive outpatient programs, and crisis hotlines utilize these strengths without requiring sustained behavioral restraint. Organizations that value quick decision-making feel more sustainable than those prioritizing deliberation.

Some therapists with this cognitive style leave clinical practice entirely for roles that leverage their assessment skills without the therapeutic relationship demands. Forensic evaluation, disability determination, organizational consultation, and executive coaching all benefit from Se-Ti processing while eliminating the burden of sustained empathic presence.

One colleague transitioned from individual therapy to program development. She applies her understanding of client needs to system design rather than direct service. Another moved into training and supervision, helping other therapists develop practical intervention skills. Both found ways to contribute to mental health without bearing the specific burden of ongoing therapeutic relationships.

What Actually Helps When You’re Already Feeling the Weight

If you’re reading this because you already recognize the burden, immediate strategies matter more than career pivots you might implement months from now.

Start by tracking which sessions energize versus deplete you. Not which clients you like, but which therapeutic activities align with your cognitive style. You might discover that assessment sessions feel engaging while maintenance sessions drain you. Or that crisis interventions restore your energy while exploratory work exhausts you.

Data on your own patterns enables strategic scheduling. Cluster your process-oriented clients on specific days, leaving other days for action-focused work. Schedule kinesthetic activities between sessions. Take your lunch break for actual movement, not documentation catch-up. Your Se needs real-world stimulation to offset the sustained stillness therapy requires.

Establish boundaries around modality pressure. If your clinical setting mandates theoretical approaches that contradict your strengths, negotiate for outcome-based flexibility. Present data on client improvement rates. Demonstrate that your solution-focused interventions produce results. Evidence speaks to administrators more than personality preference.

Connect with other ESTP therapists. The isolation of feeling like the only action-oriented clinician in a process-heavy field compounds the burden. Peer consultation with practitioners who share your cognitive style validates your experience and generates practical strategies. Organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness offer resources for mental health professionals seeking peer support networks.

Consider supplementing your income with work that leverages rather than restrains your gifts. Crisis consultation, training delivery, or program evaluation can provide professional outlets where your Se-Ti excels. You’re not abandoning therapy. You’re creating balance between cognitive restraint and cognitive expression.

Permission to Practice Differently

The therapeutic field perpetuates a fiction that good therapy looks the same regardless of practitioner type. Training emphasizes adapting yourself to established modalities rather than finding modalities that suit your cognitive architecture.

Action-oriented therapists don’t need to become more patient, more process-oriented, or more comfortable with ambiguity. These aren’t developmental goals. They’re requests to function as a different type. Imagine asking an INFJ to become more action-impulsive or an ISTJ to embrace spontaneous unstructured sessions. The request itself reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of cognitive function.

You have permission to practice therapy in ways that honor your wiring. Specializing in brief interventions aligns with ESTP strengths. Focus on behavioral change rather than insight development when it matches your cognitive style. Structure sessions around concrete goals instead of open-ended exploration. Work in crisis settings rather than maintenance settings. Leave clinical practice if the cognitive burden consistently outweighs the professional reward.

The mental health field benefits from cognitive diversity among practitioners. Clients with different needs require therapists with different strengths. Your action orientation isn’t a therapeutic limitation. It’s a specific strength that serves specific populations. The key lies in finding professional contexts where your gifts energize rather than exhaust you.

Sarah, the colleague from the opening, eventually transitioned to crisis work at a hospital emergency department. She still does therapy. But the therapy she does requires exactly what comes naturally: rapid assessment, immediate intervention, concrete action plans, and brief contact. Her gifts no longer burden her because the setting was designed for her cognitive style.

Not every action-oriented therapist needs to leave outpatient practice. But every practitioner with this cognitive style deserves to evaluate honestly whether their current professional structure sustains or depletes them. The burden you feel isn’t personal failure. It’s structural mismatch. And structural problems require structural solutions, not increased endurance.

Explore more ESTP and ESFP professional insights in our complete MBTI Extroverted Explorers Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life after spending years in the agency world managing Fortune 500 accounts. After two decades of navigating fast-paced corporate environments, he discovered that understanding personality differences transformed both his professional effectiveness and personal wellbeing. He created Ordinary Introvert to share insights about personality type, career alignment, and authentic professional identity. His experience supervising diverse teams taught him that cognitive differences aren’t obstacles to overcome but strengths to leverage strategically.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can ESTPs be effective therapists despite the challenges described?

Absolutely. ESTPs excel in therapeutic contexts that align with their cognitive strengths: crisis intervention, brief solution-focused work, behavioral therapies, and action-oriented modalities. The challenge emerges when ESTPs practice long-term process-oriented therapy that requires sustained behavioral restraint. Effectiveness depends on finding the right therapeutic setting and modality, not changing fundamental cognitive style. Many successful ESTP therapists specialize in areas where rapid assessment and immediate intervention represent optimal practice rather than limitations.

How is ESTP therapist burnout different from general therapist burnout?

ESTP burnout stems primarily from sustained cognitive restraint rather than emotional absorption. While feeling-dominant types burn out from taking on client emotions, ESTPs exhaust themselves suppressing their natural impulse toward immediate action and problem-solving. Research shows that practitioners working against their type preferences use significantly more cognitive resources per session. For ESTPs, the burnout manifests as physical restlessness, frustration with process-oriented work, and eventual sudden disengagement after years of high performance.

What therapeutic modalities work best for ESTP practitioners?

Solution-focused brief therapy, behavioral activation, dialectical behavior therapy, exposure therapy, and motivational interviewing all align well with ESTP cognitive preferences. These approaches emphasize concrete action, measurable outcomes, time-limited intervention, and practical problem-solving. They leverage the ESTP’s Se-Ti strengths (environmental awareness and logical framework construction) without requiring extended tolerance for ambiguity or open-ended emotional exploration. Many ESTPs also thrive in crisis counseling and emergency mental health settings.

Should ESTPs avoid becoming therapists altogether?

Not at all. The mental health field needs cognitive diversity among practitioners. However, ESTPs should carefully consider their practice setting, client population, and therapeutic modality during training. Specializing in crisis work, short-term interventions, or behavioral therapies allows ESTPs to provide valuable service while honoring their cognitive architecture. The challenge isn’t whether ESTPs should practice therapy, but rather finding professional contexts where their natural strengths energize rather than exhaust them. Strategic career planning during graduate training can prevent later structural mismatches.

What are early warning signs that an ESTP therapist needs to adjust their practice?

Key indicators include dreading clients who “just want to talk,” increased physical restlessness during sessions, mentally solving problems while performing active listening, and envying colleagues in more action-oriented roles. These signals suggest growing misalignment between cognitive style and professional demands rather than incompetence or lack of commitment. Additional markers include scheduling back-to-back sessions to minimize total chair time, feeling simultaneously underutilized and depleted, and experiencing relief when process-oriented clients cancel. Recognition of these patterns enables strategic adjustments before reaching complete burnout.