Three hours into the quarterly board meeting, I could feel the mask beginning to crack. I’d spent the morning being the version of myself everyone expected: engaged, articulate, asking the sharp questions that moved discussions forward. But somewhere between the budget review and the strategic planning session, my brain started moving through molasses. Words that usually came easily now required mining. The confident executive voice I’d carefully constructed over two decades was running out of fuel.

What nobody in that room understood was that I’d be completely useless for the rest of the day. Maybe longer.

If you’ve ever left a meeting feeling like you’ve run a marathon despite sitting in a chair for hours, you’re experiencing something psychologists are just beginning to quantify. Research published in Scientific American suggests that up to 90 percent of people fall somewhere in the middle of the introversion-extroversion spectrum, often displaying characteristics of both personality types depending on the situation. This middle ground, called ambiversion, helps explain why many introverts can perform brilliantly in social situations but pay a steep price afterward.

The Performance Trap Nobody Talks About

During my years running a creative agency, I learned to be whoever the room needed me to be. Client presentations demanded charisma. Team meetings required inspirational energy. Pitch sessions needed calculated confidence. I got good at it, too. So good that colleagues would often express surprise when I’d turn down after-work drinks or disappear during lunch breaks.

The truth? Every high-energy meeting was a conscious performance. Not fake, exactly, but deliberate. I was drawing from a finite reserve that needed careful management.

Psychology research from Simply Psychology explains that ambiverts can exhibit both introverted and extroverted traits, but this flexibility comes with a cost. When you can turn on extroverted behavior when needed, it’s tempting to keep doing it even as your internal battery depletes to dangerous levels.

What makes this particularly challenging is that the performance often works. Clients loved my energy. Colleagues appreciated my engagement. Nobody saw the crash coming because nobody saw me during the crash. I made sure of that.

The Science Behind the Crash

Your brain doesn’t care how well you performed in that meeting. It only knows that social interaction requires significant cognitive resources, and those resources are now depleted.

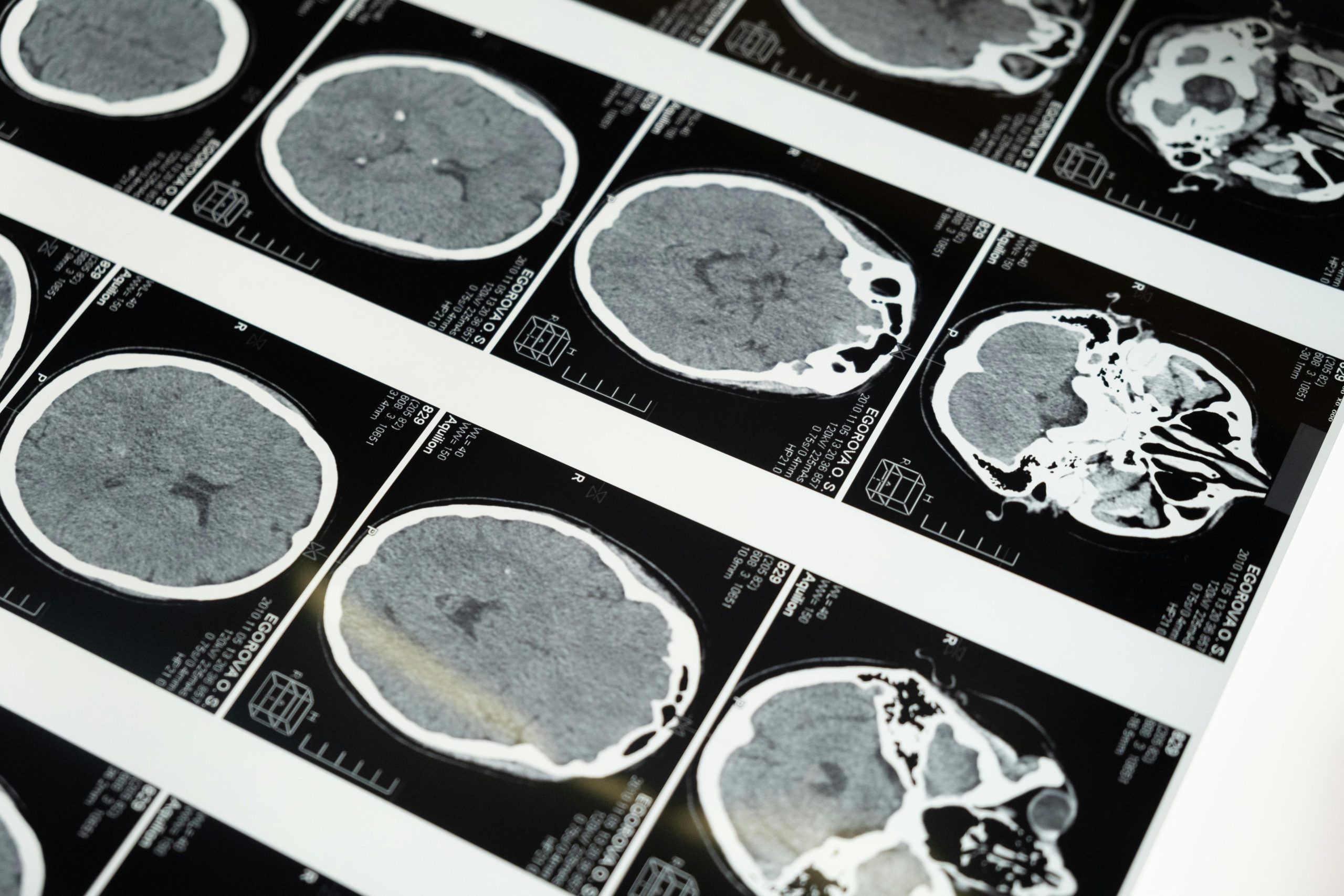

Neuroscience research on social batteries reveals that during social engagement, the anterior cingulate cortex maintains heightened activity. This brain region responsible for social monitoring creates elevated nervous system arousal. For introverts, this arousal triggers increased cortisol production and accelerated depletion of dopamine and norepinephrine, neurotransmitters crucial for sustained attention.

Translation? Your body treats extended social interaction like a stressor, even when the interaction itself is positive.

I noticed this in my own patterns. After particularly intense client meetings, I’d feel physically fatigued despite minimal physical activity. My decision-making suffered. Tasks that normally took 20 minutes would stretch to an hour. The mental fog wasn’t laziness or lack of motivation. It was neurological reality.

Research from Psych Central indicates that social interactions extending over three hours can lead to post-socializing fatigue, with introverts experiencing this threshold more quickly than extroverts. When you’re performing extroverted behavior while wired for introversion, you’re essentially running your nervous system in overdrive.

Many introverts describe this experience using battery metaphors. Your social battery drains, and unlike extroverts who recharge through continued interaction, you need genuine solitude to restore capacity. Trying to push through only depletes reserves further, leading to what some call an “introvert hangover” that can last for days.

Meeting Culture Makes It Worse

Modern workplace culture has made this pattern more challenging. Back-to-back video calls became normalized during the pandemic and never quite went away. Calendar gaps disappeared. The concept of transition time between meetings became almost quaint.

A study published in the PMC journal explored meeting recovery and found that people need time to transition between meetings and other work. This recovery period isn’t optional or a sign of weakness. It’s necessary for cognitive shifting and task switching. Without it, meeting fatigue compounds throughout the day.

When I look back at my most difficult professional periods, they all shared one characteristic: meeting density. Weeks where my calendar looked like a game of Tetris, with every block filled and no breathing room. During those times, I’d become short-tempered, make careless errors, and struggle with basic decisions. Not because the work was harder, but because I never had time to recover from the performance required in each meeting.

The research confirms what many introverts instinctively know: meeting quality matters as much as meeting quantity. Relevant, well-structured meetings with clear outcomes create less fatigue than unfocused discussions that meander without purpose. But even good meetings drain energy when stacked without recovery time.

If you find yourself dreading your calendar, canceling personal plans to recover from work weeks, or feeling exhausted despite accomplishing little tangible work, meeting fatigue is likely a factor. Just like introverts often struggle with phone calls for similar energy-drain reasons, meetings create sustained cognitive load that compounds over time.

The Hidden Cost of Code-Switching

What makes the meeting crash particularly insidious is that the performance itself often feels necessary. You’re not being dishonest by being energetic in meetings. You’re meeting professional expectations. But there’s a difference between authentic enthusiasm and sustained performance, and your nervous system knows it.

Psychology Today research on why socializing drains introverts explains that this drain relates to dopamine reward systems. Extroverts have more active dopamine systems, meaning social interaction genuinely energizes them. Introverts process dopamine differently, finding excessive stimulation overwhelming rather than rewarding.

When you force extroverted behavior, you’re working against your natural wiring. It’s like trying to write with your non-dominant hand. You can do it, and with practice you might get pretty good at it, but it requires constant conscious effort that your dominant hand wouldn’t need.

During my agency years, I developed what I later recognized as a professional persona. This version of me was confident, quick-witted, comfortable commanding a room. It wasn’t fake, but it was amplified. I was taking genuine parts of my personality and turning up the volume. The problem? You can’t sustain amplification indefinitely. Eventually, the signal distorts, or the equipment overheats.

The crash after meetings isn’t just physical tiredness. It’s the cognitive and emotional cost of sustained performance. Your brain has been monitoring itself, adjusting your tone, managing your energy level, reading social cues, formulating responses, and maintaining the performance simultaneously. That’s exhausting work, even when you’re good at it.

Recovery Looks Different for Everyone

Once you understand the pattern, you can start managing it more intentionally. Recovery isn’t one-size-fits-all, but certain principles hold across different situations.

First, accept that recovery is necessary, not optional. Trying to power through post-meeting fatigue is like trying to drive on empty. You might make it a few more miles, but you’re gambling with consequences. In my case, pushing through recovery time meant making poor decisions, damaging relationships with curt responses, and ultimately taking longer to restore function than if I’d just rested initially.

Second, build recovery time into your schedule proactively. One tactic that worked for me was blocking 30 minutes after any meeting longer than an hour. On my calendar, these showed as “Focus Time” or “Admin Work,” which was technically accurate since I used them to process meeting outcomes. But really, these blocks were recovery periods where I’d close my office door, put on headphones, and let my nervous system downshift.

Third, recognize that recovery needs vary by meeting type. All-day workshops with multiple people drain differently than one-on-one strategic sessions. Virtual meetings create different fatigue than in-person interactions. A study on meeting fatigue and stress found that 60 percent of people spending more than 15 hours weekly in meetings reported severe stress levels, with back-to-back scheduling particularly problematic.

Pay attention to your own patterns. Which meeting types leave you most drained? I discovered that client presentations exhausted me more than internal team meetings, even when the team meetings lasted longer. Knowing this helped me schedule recovery time more effectively.

Fourth, consider geographic factors in your recovery strategy. Just as some introverts find small college town living more conducive to managing social energy than big cities, your physical environment affects recovery capacity. My office door became sacred space. Open office plans, unfortunately, made recovery nearly impossible.

Redefining Professional Success

Perhaps the most important shift is reconsidering what professional competence looks like. For years, I measured my success by how well I could match extroverted standards. Charismatic presentations. Energetic team leadership. Constant availability. Looking back, these were arbitrary metrics that served someone else’s definition of effectiveness.

The quality of my strategic thinking didn’t improve because I could sustain high energy in eight consecutive meetings. My creative problem-solving actually suffered when I prioritized performance over restoration. The work that genuinely moved the agency forward happened during the quiet periods I initially felt guilty about needing.

Finding ways to contribute value without constantly performing became a turning point. Written updates instead of verbal reports. Pre-reads that made meetings shorter and more focused. Strategic use of presence versus constant availability. These weren’t compromises. They were optimizations based on understanding how my brain actually works.

Some of the most effective professionals I’ve encountered understand this intuitively. They structure their days around energy management, not just time management. They communicate their needs clearly: “I’ll be heads-down this afternoon” or “I need 15 minutes between calls to process notes.” This isn’t weakness. It’s self-awareness translated into sustainable performance.

Whether you’re handling financial decisions that require deep focus or engaging with complex political issues, preserving cognitive resources matters more than maintaining constant social availability.

Building Systems That Work With Your Wiring

Once you accept that meeting performance and post-meeting crashes are part of your reality, you can start building sustainable systems rather than fighting your nature.

Calendar management becomes strategic rather than reactive. Block recovery time first, then add meetings. Treat these blocks as seriously as client commitments. When someone wants to schedule during your recovery period, you’re genuinely unavailable, just as if you had another meeting.

Meeting preparation shifts focus. Instead of psyching yourself up for performance, consider how to achieve meeting objectives while minimizing energy expenditure. Can you circulate pre-reading that reduces verbal explanation? Can someone else lead certain agenda items? Can you propose a written update instead?

Post-meeting protocol matters. Rather than immediately diving into the next task, spend five minutes in transition. Close your eyes. Take deep breaths. Let your nervous system recognize the performance is over. This brief pause can significantly reduce overall recovery time.

Communication becomes clearer. Instead of mysterious blocked calendar time, be direct: “I have back-to-back meetings this morning and need recovery time this afternoon.” Most people respect clarity more than vague unavailability.

Environment matters too. If possible, create physical spaces that support recovery. My office became optimized for restoration: dim lighting, comfortable chair, door that actually closed. Just like students returning to school need strategies for managing classroom energy, professionals need workplace environments that support cognitive recovery.

The Long View

Meeting fatigue and post-performance crashes aren’t problems to solve. They’re realities to manage. The question isn’t how to stop crashing after meetings but how to structure your work life so the crashes don’t derail everything else.

Looking back at my agency years, I wish I’d understood this earlier. I spent a decade thinking something was wrong with me because I couldn’t sustain the energy levels I saw in extroverted colleagues. The truth? They weren’t sustaining anything. They were genuinely energized by what exhausted me, just as I found deep satisfaction in solitary strategic work that would bore them senseless.

Different wiring, different needs, different optimal conditions. Not better or worse, just different.

Whether you work in tech environments or other fields, this understanding can transform your relationship with professional demands. You stop fighting yourself and start working with your natural patterns. The performance still happens when needed, but it’s strategic rather than constant. The crashes still occur, but they’re planned for rather than crisis-managed.

The irony? Once I stopped trying to be constantly “on,” my actual impact increased. Strategic presence beats exhausted omnipresence. Deep work during recovery periods often produces better results than forcing productivity while depleted. Colleagues learned they could trust my judgment more during focused conversations than scattered participation in every discussion.

Your nervous system has been trying to tell you something with these post-meeting crashes. Maybe it’s time to listen.

Explore more General Introvert Life resources in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an extroverted introvert?

An extroverted introvert, or ambivert, is someone who can display both introverted and extroverted traits depending on the situation. Research suggests up to 90 percent of people fall in this middle ground on the personality spectrum. These individuals can perform well in social settings and meetings but require significant recovery time afterward, unlike true extroverts who gain energy from social interaction.

Why do I crash after meetings even when they go well?

Meeting fatigue occurs because social interaction requires sustained cognitive resources. Your anterior cingulate cortex maintains heightened activity during meetings, triggering cortisol production and depleting neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine. This neurological process creates genuine exhaustion regardless of meeting quality or outcomes.

How long does it take to recover from meeting fatigue?

Recovery time varies by individual and meeting intensity. Research indicates that social interactions over three hours can lead to post-socializing fatigue lasting several hours to days. Most people need 30-60 minutes of quiet transition time after intense meetings, with longer recovery periods needed after multiple back-to-back meetings or all-day events.

Is performing in meetings unhealthy for introverts?

Occasional performance isn’t harmful, but sustained code-switching without adequate recovery leads to burnout. When you consistently force extroverted behavior while wired for introversion, you’re running your nervous system in overdrive. The key is balancing necessary professional performance with sufficient recovery periods rather than maintaining constant high energy.

How can I reduce meeting fatigue at work?

Block recovery time in your calendar after meetings lasting over an hour. Avoid back-to-back scheduling when possible. Advocate for meeting agendas and pre-reads to reduce verbal processing demands. Create quiet spaces for recovery and be clear about your availability. Structure your days around energy management, not just time management.