The creative director’s email landed in my inbox at 3:47 PM, requesting an “urgent” presentation to the full executive team. My stomach dropped. Twenty years in advertising and marketing had taught me plenty about visual communication, brand strategy, and creative excellence. What those years hadn’t fixed was the cold sweat that formed whenever I faced a room full of people expecting me to perform.

I used to think something was fundamentally broken in me. How could someone who spent decades leading creative teams at agencies working with Fortune 500 brands still feel their throat tighten before client pitches? The answer, I eventually discovered, wasn’t that I was broken. I was a socially-anxious creative building success on my own terms, and there are far more of us than anyone talks about.

Graphic design attracts people who think in images, who communicate through visual language rather than spoken words. For many of us, the appeal of design work lies partly in its solitary nature. You, your computer, and the blank canvas of possibility. But the industry itself often demands something different: client presentations, team collaborations, networking events, and the constant pressure to sell yourself alongside your work.

If that tension feels familiar, you’re in exactly the right place. This isn’t advice from someone who conquered social anxiety through sheer willpower. It’s a practical guide from someone still navigating these waters, sharing what actually works for building a thriving design career while honoring the reality of anxious tendencies.

Why Graphic Design Attracts Socially-Anxious Minds

The relationship between creativity and anxiety isn’t accidental. A 2011 Swedish study led by psychiatry consultant Simon Kyaga found that anxiety appears more frequently among creative professionals than in the general population. Photographers, writers, and graphic designers all showed elevated rates compared to other fields. The researchers suggested that the same imaginative capacity that fuels creative work also enables vivid visualization of worst-case scenarios.

This connection makes sense when you consider what design work actually requires. Graphic designers spend hours considering how audiences will perceive their work. They anticipate reactions, imagine problems, and mentally test solutions before pixels ever hit the screen. That same anticipatory thinking, applied to social situations, becomes anxiety. The skill that makes you good at predicting how a logo will be received is the same skill that has you rehearsing conversations for days beforehand.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, graphic designers earn a median annual wage of $61,300, with about 20,000 openings projected each year through 2034. The field offers genuine career stability for those who build their skills, particularly as digital design continues expanding. More importantly for anxious creatives, much of this work can be structured to minimize the social demands that drain our energy.

The question isn’t whether anxious people can succeed in graphic design. Clearly, many do. The question is how to structure that success in ways that don’t require performing as someone you’re not.

The Unique Advantages Anxious Designers Bring to the Table

I spent years treating my anxiety as a liability, something to hide from clients and colleagues. It took burning out twice before I recognized that some of my most valued professional qualities emerged directly from anxious tendencies.

Anxious perfectionists catch errors others miss. We triple-check color specifications, verify file formats, and notice when kerning looks slightly off. Clients may never know why our work feels more polished than competitors’, but that obsessive attention to detail shows in the final product. The same hyper-vigilance that exhausts us socially becomes an asset when applied to design quality.

We also tend toward deeper preparation. An anxious designer walking into a client meeting has usually researched the company, reviewed competitors, and prepared for questions that might arise. This thoroughness isn’t just anxiety management; it’s professional excellence that builds client trust. As one design industry publication noted, the self-critical nature inherent in anxiety can encourage rigorous thinking and higher quality outputs.

Perhaps most valuably, anxious introverts often develop exceptional written communication skills. When speaking feels overwhelming, writing becomes our primary voice. Email, project briefs, and detailed documentation become strengths rather than compromises. Many clients actually prefer working with designers who communicate clearly in writing over those who promise everything in meetings but deliver confusing results.

Building Your Career Path: Agency vs. Freelance vs. In-House

Every career path in design carries different social demands. Understanding these differences lets you make strategic choices rather than stumbling into environments that amplify anxiety.

Agency work typically involves the highest social pressure. Constant client presentations, team brainstorms, and the performance culture that permeates many creative agencies can overwhelm anxious designers quickly. I watched talented colleagues flame out in agency environments not because their work suffered, but because the performative aspects depleted them completely. That said, some smaller boutique agencies offer more protected creative roles where design quality matters more than presentation skills.

In-house positions often provide more predictability. You work with the same colleagues, understand the brand deeply, and face fewer high-stakes presentation situations. The trade-off is less variety in projects and sometimes feeling isolated as the only designer. For anxious creatives who thrive with routine and familiar relationships, in-house work can offer sustainable careers without constant social negotiation.

Freelancing presents a paradox for socially-anxious designers. On one hand, you control your environment completely. Work from home, choose clients carefully, communicate primarily through email. On the other hand, you must handle all client acquisition, negotiation, and relationship management yourself. The reality is that freelancing requires developing specific skills around client communication, but these can be systematized in ways that reduce anxiety significantly.

As Rasmussen University notes, graphic design ranks among the top creative careers for introverts because designers can complete most work independently while collaborating in small, controlled settings. The key is choosing and shaping your work situation rather than accepting whatever environment you land in.

Client Communication Strategies That Actually Work

The worst advice I ever received was to “just push through” social discomfort with clients. Pushing through might work for occasional challenges, but it’s not sustainable for ongoing professional relationships. Better to develop systems that reduce anxiety while maintaining professional effectiveness.

Start with communication channel management. Most client interactions don’t actually require real-time conversation. Project updates, revisions, and feedback can flow through email or project management tools. When I transitioned from agency work to consulting, I began explicitly stating my communication preferences to clients: “I find I do my best work when I can respond thoughtfully to feedback in writing. Let’s use email for ongoing communication and save video calls for kickoff and major milestone reviews.”

Surprisingly, most clients respect this. They’re busy too. They appreciate not having their calendars cluttered with calls when an email would suffice. The clients who insist on constant synchronous communication often aren’t ideal fits anyway; they typically struggle with boundaries in other areas too.

For the meetings that do happen, preparation becomes your anxiety anchor. Create detailed agendas. Write out key points you want to communicate. Have your screen ready to share so you can direct attention to the work rather than yourself. I keep a “meeting prep” template that I complete before any client call, including anticipated questions and my planned responses. This might sound over-prepared, but it transforms meetings from unpredictable social performances into structured conversations where I know my part.

Consider positioning yourself as a specialist rather than a generalist. Specialists get hired for expertise, not personality. When clients seek you out for specific skills, whether that’s brand identity systems, publication design, or digital interface work, the relationship centers on your capabilities rather than your social presentation. UX design work presents particular challenges around client interaction, but even that field can be navigated with the right communication systems.

Building a Portfolio That Sells Without Selling

For anxious creatives, the portfolio becomes even more critical. A strong portfolio speaks for you, reducing the need for verbal self-promotion that drains our energy. The goal is creating materials that do the persuading so you don’t have to.

Every project in your portfolio should tell a complete story: the problem, your approach, the solution, and ideally the results. Written case studies eliminate the need to explain your process repeatedly. When potential clients can understand your thinking through your portfolio, initial conversations become less about convincing and more about clarifying fit.

Include process documentation alongside finished work. Sketches, iterations, and decision points show how you think, not just what you produce. This depth appeals to clients who value thoughtfulness, exactly the kind of clients anxious designers typically work best with. Clients who hire based on flashy presentations often want flashy working relationships; clients who appreciate documented process usually prefer substantive collaboration.

Your portfolio website should work as a qualifying tool. Be explicit about your working style, communication preferences, and ideal project types. Clients who self-select based on this information arrive already aligned with how you operate. Those who wouldn’t be good fits move on before you’ve invested any energy.

If you’re wondering whether design can actually provide sustainable income, the answer depends heavily on positioning. Designers who compete primarily on price face a race to the bottom. Those who position on expertise, process quality, and specific value propositions can command rates that make sustainable careers possible.

Managing the Emotional Labor of Creative Work

Design work involves inherent emotional vulnerability. You create something, show it to others, and wait for judgment. Even after twenty years, that moment before client feedback arrives still activates my anxiety. The difference now is that I’ve built systems for managing it.

Separating your identity from your work sounds like standard creative advice, but for anxious designers it requires specific practices. I keep a “feedback file” where I document client responses to my work over time. When criticism hits hard, I can reference this file to remember that one piece of negative feedback doesn’t represent the pattern of my career. This concrete record counterbalances the anxious mind’s tendency to catastrophize.

Build recovery time into your schedule. After high-stakes presentations or difficult feedback conversations, don’t immediately jump into the next project. Anxious nervous systems need longer to return to baseline. What might take a colleague thirty minutes to shake off could occupy your brain for the rest of the day. Schedule accordingly.

Grand Canyon University’s research on creative careers notes that introverts bring exceptional focus and thoughtfulness to design work, but this comes with the need for more solitary processing time. Honor that need rather than fighting it. Your best work emerges when you’re not depleted, and anxious designers deplete faster in social contexts.

Consider building a support network of other anxious creatives. Online communities allow connection without the pressure of in-person networking. Finding peers who understand the specific challenges of socially-anxious creative work provides both practical advice and the reassurance that you’re not alone in this. Many careers can accommodate social anxiety effectively, and connecting with others who’ve built sustainable paths offers invaluable perspective.

Remote Work: The Anxious Designer’s Best Friend

The shift toward remote work has been transformative for socially-anxious designers. Controlling your environment eliminates many anxiety triggers that office settings constantly activate. No surprise drop-ins at your desk. No forced small talk in the break room. No performance pressure in open floor plans designed for extrovert collaboration.

Remote graphic design work has expanded dramatically, with positions available across time zones and industries. LinkedIn research on remote design success emphasizes that thriving in distributed work requires strong written communication, self-discipline, and clear boundary setting. These are skills anxious designers often develop naturally as survival mechanisms.

Structuring remote work to manage anxiety means being intentional about when and how you interact. Batch communication into specific times rather than responding constantly. Use asynchronous video tools like Loom for updates that don’t require live interaction. Create clear boundaries around “meeting days” versus “heads-down work days” so you know when social energy will be required.

Your home workspace matters significantly. Anxious minds benefit from order and predictability. A dedicated workspace, even a small one, signals to your brain that it’s time to work. Comfortable lighting, minimal clutter, and personal touches that make you feel grounded all contribute to reducing baseline anxiety while you design.

According to Coursera’s analysis of careers for introverts, graphic design ranks highly precisely because the work itself is independent even when the role sits within a larger organization. Remote positions amplify this independence, allowing anxious designers to contribute excellent work without the social overhead of traditional office environments.

Practical Tools and Systems for Daily Management

Beyond career strategy, day-to-day anxiety management makes sustainable design careers possible. These aren’t therapeutic interventions; they’re practical systems that reduce friction between anxious tendencies and professional demands.

Email templates save enormous mental energy. Create templates for common communications: project kickoffs, requesting feedback, responding to revisions, handling scope creep. When anxiety makes every email feel high-stakes, templates remove the paralysis of starting from scratch. Customize as needed, but begin with the structure already built.

Calendar blocking protects your energy. Schedule not just meetings but focused work time, email processing, and recovery periods. Anxious brains function better with predictability. Knowing that you have protected creative time tomorrow makes today’s client call feel more manageable.

Project management tools externalize the mental load that anxious minds constantly carry. When every deadline, requirement, and communication lives in a system rather than your head, you free up cognitive space for actual creative work. Tools like Notion, Asana, or even structured folders reduce the background anxiety of forgetting something important.

Monster’s career research confirms that graphic design offers clear project structures with defined goals and objectives. This structure provides a sense of certainty that anxious minds crave. Leverage that inherent structure by adding your own systems on top. The more predictable your workflow, the less anxiety activation throughout your workday.

When to Push Through vs. When to Restructure

Not every anxious situation requires restructuring. Some growth happens by doing hard things. The question is distinguishing between productive discomfort and unsustainable strain.

Productive discomfort feels challenging but possible. You might dread a presentation, but you can prepare adequately and recover afterward. The anxiety is proportionate to the actual stakes, and you can function effectively despite feeling uncomfortable. This kind of discomfort often leads to skill development and expanded capacity over time.

Unsustainable strain looks different. Anticipatory anxiety lasting days or weeks. Physical symptoms that interfere with sleep or concentration. Avoidance behaviors that limit your career growth or income. When anxiety reaches this level, pushing through isn’t building resilience; it’s depleting reserves you need for actually doing your work.

The distinction matters because blanket advice to “face your fears” ignores the reality of anxiety disorders versus ordinary nervousness. If your anxiety significantly impairs functioning, professional support through therapy or medication can be transformative. Cognitive behavioral therapy in particular has strong evidence for anxiety management, and many therapists now offer video sessions that don’t require leaving your controlled environment.

I wasted years treating severe anxiety as a character flaw to overcome through willpower. Getting actual treatment didn’t eliminate my anxious tendencies, but it reduced them to manageable levels. The energy I was spending on constant anxiety management became available for creative work instead.

Building Long-Term Success on Your Own Terms

Success in graphic design doesn’t require transforming into an extroverted self-promoter. It requires building a career structure that plays to your actual strengths while managing around your challenges. This is true for everyone, but anxious designers often need to be more intentional about the building.

Start by defining what success actually means for you. For some, it’s creative freedom and project variety. For others, it’s income stability and predictable work. For many anxious designers, it’s simply sustainable work that doesn’t require constant recovery from social exhaustion. Get clear on your actual priorities rather than inherited assumptions about what design careers should look like.

Build relationships slowly and deeply rather than broadly. Anxious designers often struggle with networking but excel at maintaining close professional relationships. Focus your limited social energy on key clients, collaborators, and referral sources rather than spreading thin across industry events you dread.

Invest in skills that multiply your value without multiplying social demands. Technical capabilities, specialized software knowledge, and niche expertise all increase what you can offer clients without requiring more face time. Clients pay premium rates for deep expertise, and expertise-based positioning reduces the need for relationship-based selling that depletes anxious designers.

Document your systems so you can replicate what works. When you find a client communication approach that reduces anxiety, write it down. When a project structure helps you work more effectively, template it. Over time, you build a personal playbook for anxious design success that becomes easier to implement.

Moving Forward with What You Have

The design industry needs anxious creatives. We bring depth, thoroughness, and sensitivity that enriches the work. The challenge isn’t fixing ourselves to fit industry expectations; it’s shaping our careers to leverage our genuine strengths.

This doesn’t happen overnight. Building a sustainable design career as a socially-anxious creative takes time, experimentation, and willingness to structure things differently than industry norms might suggest. But it’s absolutely possible. The evidence exists in every introverted, anxious designer quietly building excellent work and sustainable careers on their own terms.

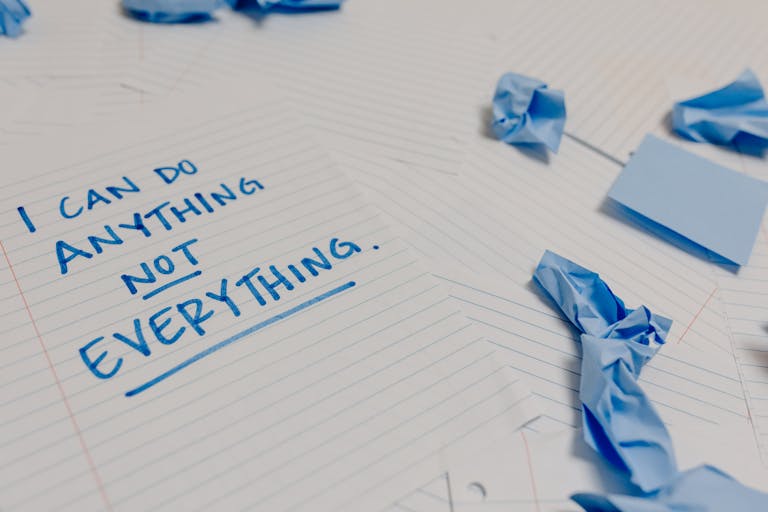

Your anxiety isn’t a barrier to design success. It’s information about what you need to thrive. Listen to it. Build around it. Use the same problem-solving creativity you apply to design work for designing your career itself. The result might not look like anyone else’s path, and that’s exactly the point.

The blank canvas that awaits your next design is the same canvas that awaits your next career decision. Both require creativity, intentionality, and willingness to iterate. You already have the skills. Now apply them to building a creative life that actually fits who you are.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you have a successful graphic design career with social anxiety?

Yes, absolutely. Graphic design work is primarily independent and visual, which plays to many anxious creatives’ strengths. Success requires strategic choices about work environments, client communication systems, and career positioning, but many designers build thriving careers while managing social anxiety.

Is freelance or in-house design better for anxious designers?

Both paths can work depending on individual preferences. Freelancing offers complete environmental control but requires handling all client interactions yourself. In-house positions provide stability and familiar relationships but less control over your schedule and workspace. Many anxious designers find success in both; the key is choosing intentionally rather than defaulting to whatever opportunity appears.

How do you handle client presentations when you have anxiety?

Thorough preparation is essential. Create detailed agendas, write out key points, and practice beforehand. Use screen sharing to direct attention to the work rather than yourself. Limit unnecessary meetings by establishing email as the primary communication channel for ongoing updates. When presentations are unavoidable, schedule recovery time afterward.

What graphic design specializations work best for introverts with anxiety?

Specializations with less client interaction include production design, template creation, and technical documentation design. Brand identity work can be structured with limited meetings. Digital product design for established companies often involves smaller teams and clearer processes. The key is choosing niches where expertise matters more than presentation skills.

Should I tell clients about my social anxiety?

This is a personal decision with no universal answer. Some designers find that explaining their preference for written communication helps set expectations. Others prefer framing it as a working style preference without mentioning anxiety specifically. Focus on what you need to do your best work rather than disclosure for its own sake. Clients generally care more about results than process, so emphasize your quality work and professional communication systems.

Explore more Alternative Work Models and Entrepreneurship resources in our complete Alternative Work Models and Entrepreneurship Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.