Three hours before a networking dinner, my inbox pinged with the reminder. I’d said yes three weeks ago when declining felt impossible. Now I sat at my desk, exhausted from back-to-back client meetings, drafting yet another excuse about why I couldn’t make it.

The truth? I didn’t have a good reason. I was just tired. But “I’m tired” felt inadequate, almost rude. So I crafted a story about a last-minute work crisis, sent the email, and felt worse than if I’d just gone to the dinner.

That pattern repeated for years across my advertising career. Accepting drinks with colleagues who weren’t really friends felt obligatory. Industry events that drained me still got a yes. Weekend brunches when I desperately needed quiet? Another acceptance. Each yes came with an elaborate justification whenever I eventually had to cancel.

Declining invitations creates anxiety for most people, but especially for those of us who value connection despite our need for solitude. Our General Introvert Life hub explores these social navigation challenges, and learning to say no without explanation stands as one of the most valuable skills you can develop.

Research from Julian Givi and Colleen Kirk, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, reveals something surprising: we dramatically overestimate how upset people will be when we decline their invitations. In studies involving over 2,000 participants, including real couples extending and declining invitations to each other, invitees consistently predicted the inviter would feel much more angry and disappointed than they actually did.

The Psychological Weight of Saying No

Something shifts when someone extends an invitation. Suddenly you’re not just making a choice about your evening, you’re managing their potential disappointment, protecting the relationship, and justifying your preferences.

Psychologist Nicole LePera identifies our conditioning to explain ourselves as a core issue. According to LePera, we’ve been taught that saying no requires justification, creating a cycle where the explanation becomes the point of pushback rather than the decision itself.

During my agency years, I watched this dynamic play out constantly. Team members would decline project invitations with elaborate explanations about their workload, family commitments, or scheduling conflicts. The more detailed the explanation, the more questions they faced. “Can’t you just do this part?” “What if we moved the deadline?” “Couldn’t someone else handle your other commitment?”

Those who simply said “I won’t be able to take this on” faced far less negotiation. The certainty of the statement, absent justification, signaled a firm boundary rather than an opening for discussion.

Why We Feel Compelled to Explain

Psychiatrist Murray Bowen’s concept of “differentiation of self” describes the ability to maintain your sense of identity while staying connected to others. Strong differentiation means you can set boundaries without letting others’ emotional reactions dictate your decisions.

Most of us operate with lower differentiation than we’d like to admit. When someone asks us to attend their party, join their committee, or meet for coffee, their emotional investment in our answer becomes our responsibility to manage. We assume declining will damage the relationship, so we either say yes or craft elaborate explanations to soften the blow.

Research challenges this assumption. Givi’s studies found that inviters understand invitees don’t decline lightly. They consider the thought process behind the decision, not just the outcome. People in the position of being declined had better insight and were less likely to believe the other person felt angry or disappointed.

Your elaborate explanation doesn’t protect the relationship as much as you think. Often, it creates more friction by opening doors for negotiation or making the decliner feel you lack confidence in your own boundaries.

The Power of “I Don’t” Over “I Can’t”

Language shapes how both you and others perceive your boundaries. A study on self-control found that participants who used “I don’t” instead of “I can’t” when refusing temptations showed significantly enhanced psychological empowerment. Sixty-four percent of those using “I don’t” chose healthy options compared to just 39% using “I can’t.”

“I can’t attend your party” suggests external obstacles you could theoretically overcome. “I don’t attend evening events on weekdays” communicates a personal policy, a boundary that’s part of your values rather than a temporary constraint.

Leading a team at my agency, I watched employees struggle with this distinction constantly. “I can’t take on this project” invited questions about capacity, priorities, and urgency. “I don’t accept projects without a two-week lead time” ended the conversation. Same boundary, vastly different reception.

People respect stated policies more than circumstantial obstacles. Your “I don’t” signals commitment to your values and makes pushing back feel like challenging your identity rather than solving a logistics problem.

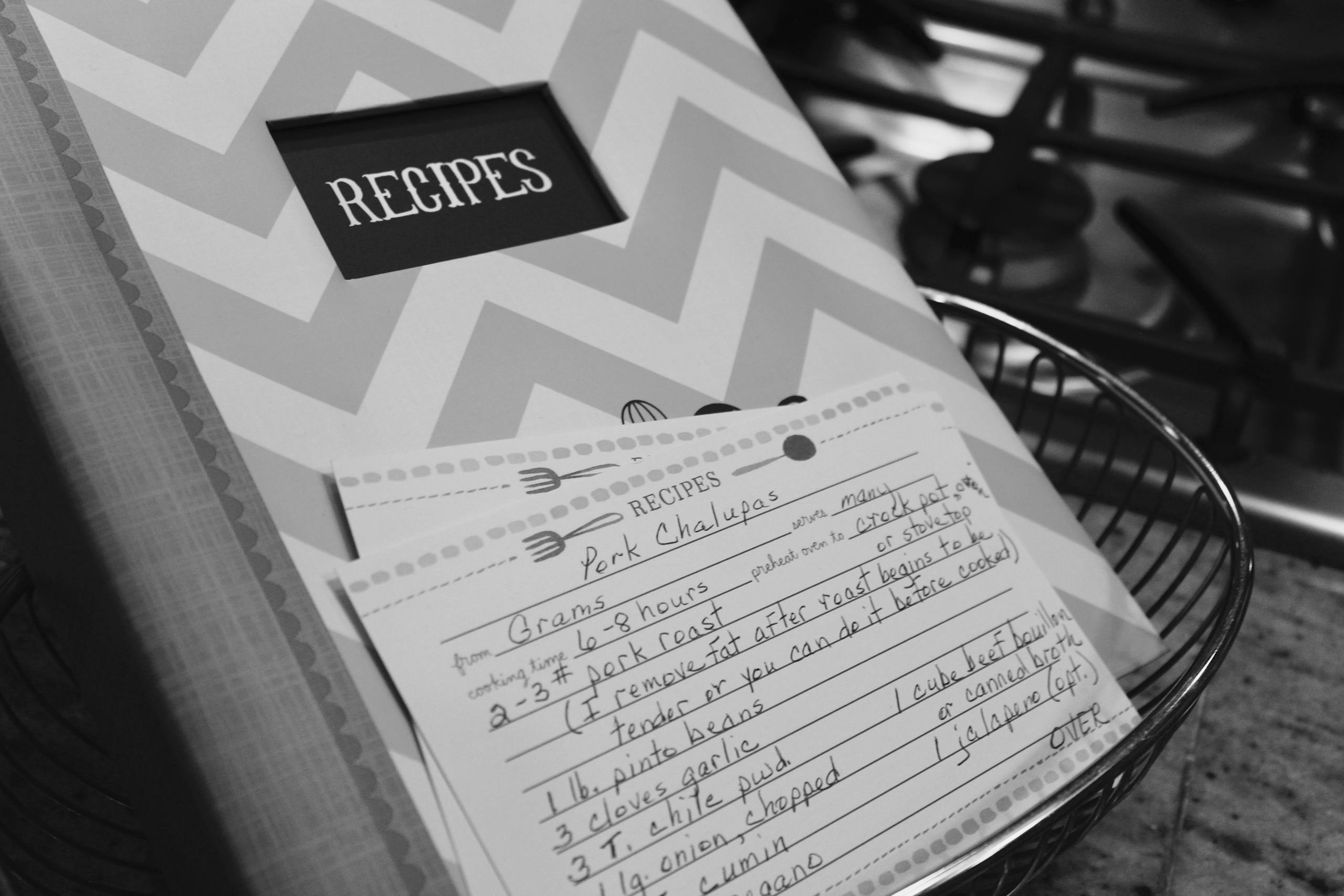

Scripts for Declining Without Explanation

Effective boundary-setting communication follows a simple structure: acknowledge the invitation, state your decision clearly, and close the conversation. Clear communication without lengthy justification protects your time while demonstrating respect for the other person.

Start with gratitude: “Thank you for thinking of me” or “I appreciate the invitation.” This acknowledgment validates their gesture without obligating you to attend.

State your boundary: “I won’t be able to make it” or “I’m not available that evening.” Keep this portion direct and brief. Avoid tentative language like “I don’t think I can” which suggests room for negotiation.

Close graciously: “I hope you have a wonderful time” or “Thanks again for including me.” This redirects focus back to their event rather than your absence.

Complete script: “Thank you for the invitation to your dinner party. I won’t be able to attend, but I hope you have a wonderful evening.”

Notice what’s missing: no excuse about scheduling conflicts, no mention of other commitments, no apology for declining. You’re not being rude, you’re being clear about your boundaries while respecting theirs enough to decline honestly rather than inventing obstacles.

For professional contexts where relationship maintenance matters more, consider these variations that maintain boundaries without explanation:

- “I appreciate you thinking of me for this committee. My current commitments won’t allow me to give it the attention it deserves.”

- “Thank you for the networking event invite. I’m being selective about evening commitments right now and won’t be able to attend.”

- “I’m grateful you included me in the wedding party invitation. I need to decline, but I’m excited to celebrate your marriage.”

Each acknowledges the invitation’s importance without detailing why you’re unavailable. The boundaries feel firm because they reference your values (giving proper attention, being selective, managing commitments) rather than temporary obstacles.

When Relationships Require More Context

Some relationships warrant slightly more information without crossing into over-explanation territory. Close friendships, family connections, and important professional relationships benefit from context that demonstrates care without justifying your decision.

My closest friend invited me to her daughter’s birthday party during a particularly intense work sprint. Declining with just “I can’t make it” would have felt cold given our relationship depth. Instead: “I need to miss Emma’s party this year, work’s been overwhelming and I’m not in a good headspace for big social events right now. Can we do something special with Emma next week, just us?”

Notice the difference between context and excuse. Context explains your current state (“work’s overwhelming, not in good headspace”) without implying those circumstances are the only reason you’re declining. An excuse would be “I have this huge deadline and my boss needs this project and I really wish I could come but…” which invites problem-solving.

Context also demonstrates care by offering an alternative that meets both people’s needs. You’re not shutting down connection, you’re protecting your capacity to show up authentically when you do connect.

Similar to managing the guilt of canceling plans, declining invitations becomes easier when you remember that authentic relationships accommodate both presence and absence.

Managing Pushback and Questions

Some people will accept your declination immediately. Others will push for explanations, try to solve your perceived obstacles, or question your decision. Prepared responses prevent you from caving to pressure or inventing elaborate excuses in the moment.

If they ask “Why can’t you come?” respond with: “I’m not able to make it work with my current commitments.” This references your overall situation without listing specific conflicts they might try to rearrange.

If they offer solutions (“What if we moved it to next week?” “Can you come for just an hour?”), acknowledge their flexibility while maintaining your boundary: “I appreciate you trying to accommodate me. I need to decline either way, but thank you for being flexible.”

For persistent questioners who won’t accept your first refusal, the broken record technique works remarkably well. Simply repeat your boundary using the same or similar language: “I understand you’d like me there, and I’m not able to attend.” Repeat as many times as necessary without adding new information or engaging in debate.

Managing a team taught me that people respect consistency more than they respect elaborate reasoning. Employees who held firm boundaries got less pushback than those who negotiated every exception. The same applies to personal invitations, your consistency signals that your boundaries are real, not suggestions open to revision.

Different Boundaries for Different Relationships

Not every relationship requires the same communication approach. Understanding which boundaries suit which contexts prevents both over-explanation with casual acquaintances and under-communication with close relationships.

Casual acquaintances and coworkers: Brief, polite declinations without explanation. “Thank you for the invitation. I won’t be able to attend.” These relationships don’t require context, and offering too much information can feel oddly intimate for the connection level.

Close friends and family: Slightly more context that demonstrates care. “I need to pass on the reunion this year, I’m focusing on recharging this month. Let’s plan something smaller together soon.” Balance honesty with boundaries, offering alternatives when you want to maintain connection.

Professional relationships: Clear boundaries with brief reasoning that maintains respect. “I appreciate the invitation to join the board. My current commitments require all my available bandwidth, so I need to decline.” Professional contexts benefit from acknowledging the opportunity’s value while maintaining your decision.

Manipulative or guilt-inducing inviters: Firm boundaries with zero explanation. “I won’t be attending.” Period. People who use guilt, manipulation, or pressure to override your boundaries don’t deserve access to your reasoning. Protecting your energy from boundary violators requires recognizing when explanation becomes ammunition for further manipulation.

New relationships where you’re establishing patterns: Clear, consistent boundaries that teach others how you operate. “I don’t do evening social events on weeknights” sets expectations early, preventing future awkwardness when you decline similar invitations.

The Guilt Factor and How to Handle It

Guilt accompanies most boundary-setting, especially when you’re new to declining without explanation. That discomfort doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong, it means you’re breaking old patterns and challenging conditioning that taught you to prioritize others’ comfort over your own needs.

After years of managing client relationships in advertising, I learned that guilt often signals growth rather than mistakes. Each time I set a firm boundary with a client, declining after-hours calls, refusing to present work before it was ready, saying no to scope creep, I felt guilty. That guilt gradually transformed into confidence as I watched relationships improve rather than deteriorate.

Clients who respected boundaries became better clients. Those who didn’t revealed themselves as poor fits for our agency. The guilt was my nervous system adjusting to prioritizing sustainable practices over people-pleasing.

Research on boundary communication emphasizes that “I don’t” statements signal control and commitment to personal values, making it harder for others to push back. When you frame your declination as a policy rather than a circumstance, guilt diminishes because you’re honoring your values rather than arbitrarily rejecting someone.

Practical strategies for managing guilt include remembering that you’re modeling healthy boundaries for others, recognizing that temporary discomfort prevents long-term resentment, and understanding that people who truly care about you want you to protect your wellbeing rather than deplete yourself attending events out of obligation.

For those wondering about the balance between setting boundaries and maintaining relationships, consider that relationships strengthened by guilt and obligation are relationships built on shaky foundations. Authentic connections can withstand honest declinations.

Building Your Declination Practice

Declining invitations without explanation becomes easier with practice, but starting requires intentional effort. Begin with low-stakes situations where relationship consequences feel minimal.

Practice scenarios might include declining a coworker’s lunch invitation when you need alone time to recharge, saying no to a casual acquaintance’s party, or skipping an optional work social event. These situations offer practice grounds for your boundary-setting language without risking important relationships.

Notice your impulse to explain or justify. When you catch yourself about to launch into reasons, pause and return to your simple script: “Thank you for asking. I won’t be able to join you.” Sit with the discomfort of not explaining. Watch how most people accept your decision and move on.

Track your experiences to reinforce learning. After each declined invitation, note the person’s reaction, your guilt level, and the outcome. Most often, you’ll discover that your feared negative consequences don’t materialize. People accept your no, relationships continue, and you’ve protected your energy for commitments that genuinely matter to you.

Graduate to higher-stakes situations as your confidence builds. Declining a close friend’s invitation, saying no to family events, or turning down professional opportunities all become manageable once you’ve proven to yourself that boundaries don’t destroy relationships, they strengthen them by ensuring you show up authentically when you do choose to participate.

What Happens After You Start Saying No

Establishing boundaries creates ripple effects throughout your social ecosystem. Some changes feel uncomfortable at first. Others bring immediate relief. All contribute to your wellbeing and relationship authenticity.

Some people will respect your boundaries immediately and appreciate your honesty. These relationships typically deepen because you’ve removed the pretense of obligation-based attendance. Your presence becomes meaningful rather than assumed.

Others will test your boundaries, pushing for explanations or trying to negotiate your decisions. Consistent application of your boundaries teaches people how to interact with you. Each time you hold firm without justifying, you reinforce that your boundaries are real and non-negotiable.

A small percentage may react negatively, expressing hurt or anger at your declinations. These reactions reveal more about their expectations than your behavior. Relationships built on your constant availability and accommodation aren’t sustainable anyway. Some connections will naturally fade as you establish healthier patterns, and that’s acceptable growth rather than relationship failure.

Most significantly, you’ll discover more energy for commitments you genuinely value. Declining the invitations that drain you creates capacity for the people and activities that energize you. Your social calendar becomes intentional rather than reactive, filled with choices that align with your values rather than obligations you couldn’t refuse.

The transition period feels awkward. You’re retraining both yourself and others to operate with clearer boundaries. Push through that discomfort. The freedom of declining invitations without explanation or guilt is worth the temporary awkwardness of establishing new patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it rude to decline an invitation without giving a reason?

Declining without detailed explanation is not rude when done with grace and appreciation. Givi and Kirk’s 2024 study found that people overestimate how upset others will be when they decline invitations. A simple “Thank you for the invitation, but I won’t be able to attend” respects both parties, you honor their gesture while maintaining your boundaries. Rudeness comes from how you communicate, not from declining itself. Gratitude, clarity, and kindness in your response demonstrates respect without requiring justification.

What if someone keeps asking why I can’t come?

Persistent questioning requires consistent boundaries. Use the broken record technique: repeat your declination using similar language without adding new information. “I appreciate your interest, but I’m not able to attend” repeated calmly as many times as necessary. Avoid the temptation to invent reasons or over-explain, as this opens doors for problem-solving and negotiation. People who respect your boundaries will accept your first answer. Those who don’t are revealing that they prioritize their preferences over your autonomy.

How do I decline invitations from close friends or family without damaging relationships?

Close relationships can accommodate slightly more context while maintaining boundaries. Share your current state without justifying your decision: “I’m overwhelmed with work right now and need quiet weekends to recharge. I won’t make it to the party, but let’s plan coffee next month.” Offer alternatives when you genuinely want to maintain connection. The key difference is context (explaining your state) versus excuse (implying circumstances are the only barrier). Strong relationships handle honest declinations better than resentful attendance.

What’s the difference between “I can’t” and “I don’t” when declining?

“I can’t” suggests external obstacles that could theoretically be overcome, inviting negotiation and problem-solving. “I don’t” communicates a personal policy or value-based decision that signals firmer boundaries. A self-control study found that “I don’t” statements enhance psychological empowerment and reduce pushback because they frame your decision as a commitment to your values rather than a temporary constraint. “I don’t attend evening events on weekdays” carries more weight than “I can’t make it tonight” because it references how you operate rather than what’s blocking you right now.

Will people stop inviting me if I decline too often?

Some people may invite you less frequently, and that’s a natural consequence of establishing boundaries. However, quality relationships persist through honest declinations. People who truly value your company will continue extending invitations because they want you there when you can genuinely show up. Those who stop inviting you after a few declined invitations likely valued your obligatory presence more than your authentic participation. What matters is receiving invitations that align with your capacity and interests from people who respect your boundaries, not maximizing your total invitation count.

Explore more boundary-setting resources in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.