Something remarkable happens inside certain brains when they encounter the world. A subtle shift in someone’s expression, a faint noise in the background, the emotional undercurrent of a conversation. Where many people filter these inputs automatically, others process them deeply, thoroughly, almost involuntarily. For years, I assumed this heightened awareness was simply a quirk of personality, perhaps even a weakness that needed managing. Discovering the neuroscience behind high sensitivity changed everything I thought I knew about how my own mind worked.

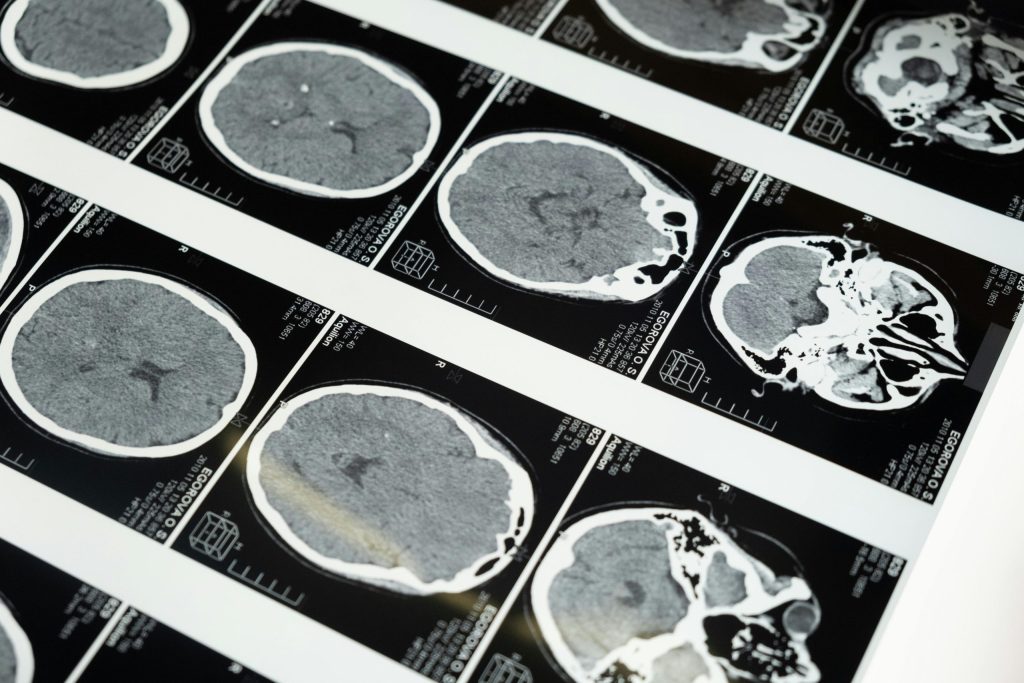

If you identify as a highly sensitive person, your brain genuinely operates differently from those around you. Functional MRI studies have revealed measurable differences in how HSP brains respond to emotional and sensory stimuli. These findings validate what sensitive individuals have sensed intuitively: their experience of the world is neurologically distinct, not imagined or exaggerated.

What Brain Science Reveals About High Sensitivity

The scientific knowledge of sensory processing sensitivity has advanced dramatically since psychologists Elaine and Arthur Aron first identified the trait in the 1990s. Initial research relied primarily on self-report questionnaires, but modern neuroimaging technology has enabled researchers to observe the HSP brain in action. According to a groundbreaking 2014 fMRI study by Acevedo and colleagues at UC Santa Barbara, individuals scoring high on sensitivity measures showed distinctive patterns of neural activation when viewing emotional images.

During my agency leadership years, I frequently noticed how certain team members seemed to pick up on client moods before anyone else did. They would mention something felt off in a meeting, and days later, we would learn about underlying concerns that had been present all along. At the time, I attributed this to intuition or experience. Now I understand there is actual brain architecture supporting these perceptions.

The research has identified several key brain regions that show enhanced activity in highly sensitive individuals. The anterior insula, cingulate cortex, and areas associated with mirror neuron activity all demonstrate heightened responsiveness. These regions govern awareness, empathy, and the processing of social and emotional information. When a highly sensitive person reports feeling deeply affected by others’ emotions, their brain is literally working harder to process that emotional data.

The Insula and Emotional Awareness

Among the most significant findings in HSP brain research is the prominent role of the insula, particularly the anterior insula. This curved structure tucked within the brain’s lateral sulcus acts as an integration center for internal and external sensory information. Research published in Scientific Reports (2022) demonstrated that sensory processing sensitivity correlates with enhanced insula activation during touch perception, suggesting the HSP brain processes physical sensations with greater depth and emotional coloring.

The insula plays a crucial role in interoception, our awareness of internal bodily states like heartbeat, breathing, and gut feelings. Highly sensitive people commonly report strong gut reactions and physical responses to emotional situations. This heightened interoceptive awareness appears to have a neurological basis in enhanced insula function. Where others might need obvious cues to recognize their emotional states, sensitive individuals receive continuous, detailed feedback from their bodies.

Working with creative teams throughout my career, I observed how some individuals could sense project momentum shifting before any metrics reflected the change. One art director I worked with could tell when a campaign concept was resonating with clients simply from the energy in early review meetings. Her insula, I now realize, was processing subtle environmental signals that others missed entirely.

Mirror Neurons and Deep Empathy

The mirror neuron system represents another crucial component of the highly sensitive brain. Mirror neurons fire when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing the same action. They form part of the neural basis for empathy, allowing us to internally simulate what others experience. In highly sensitive individuals, these systems appear to engage more readily and intensely.

Research examining HSP brain responses to images of loved ones and strangers found enhanced activation in regions associated with the mirror neuron system. This activation was particularly pronounced when viewing happy expressions, suggesting that sensitive brains are especially attuned to positive emotional states in others. The implications extend beyond simple emotion recognition into genuine emotional resonance.

This deep empathic capacity can feel overwhelming in demanding social situations. During high-stakes client presentations in my advertising career, I would absorb the anxiety and expectations in the room so completely that separating my own feelings from the ambient emotional climate became nearly impossible. Recognizing the neural mechanisms behind this experience helped me develop more effective strategies for managing my energy in intense professional environments.

The Genetic Architecture of Sensitivity

Brain differences in highly sensitive people are not learned behaviors or purely environmental adaptations. Substantial evidence points to genetic underpinnings for the trait. Research by Homberg and colleagues has linked sensory processing sensitivity to variations in genes regulating serotonin and dopamine, two neurotransmitters central to mood, reward, and information processing.

The serotonin transporter gene variant known as 5-HTTLPR has received particular attention. Individuals carrying the short allele of this gene tend to show greater environmental sensitivity, responding more strongly to stressors and to supportive conditions alike. Dopamine-related genes, particularly variants affecting the D4 receptor, have each been associated with heightened sensitivity traits. These genetic factors influence how the brain develops and how neural circuits process incoming information.

The heritability of sensitivity means that if you identify as highly sensitive, you likely have family members who share the trait. Looking back at my own family history, I can identify relatives who demonstrated classic sensitivity patterns, though they never had language for these experiences. My grandmother would become physically ill when family conflict arose, and my father needed substantial alone time to function well. The genetic thread runs clearly through generations.

Differential Susceptibility: Sensitivity as Amplification

One of the most important developments in sensitivity research is the concept of differential susceptibility. Rather than viewing sensitivity as a vulnerability that increases risk for negative outcomes, this framework recognizes sensitivity as amplification. Highly sensitive individuals respond more intensely to all environmental influences, including positive ones. Ellis and colleagues’ evolutionary neurodevelopmental theory proposes that sensitivity represents an adaptive strategy present across many species.

In supportive, nurturing environments, highly sensitive individuals often thrive beyond their less sensitive peers. They absorb lessons more deeply, respond more fully to encouragement, and develop more nuanced social skills. In adverse conditions, sensitivity can magnify harmful effects. This bidirectional susceptibility explains why some sensitive children flourish remarkably while others struggle despite similar baseline traits.

Grasping differential susceptibility reframed how I thought about my own professional development. Early in my career, I worked under a mentor who provided consistent, constructive feedback and genuine support. I flourished in ways that surprised even me. Later, in a more chaotic, critical environment, my performance suffered disproportionately. The environments had changed, not my fundamental capabilities. My sensitivity amplified whatever context I found myself in.

Depth of Processing: The HSP Cognitive Style

Brain imaging research consistently shows that highly sensitive people engage in deeper cognitive processing of incoming information. This depth manifests in the prefrontal cortex and areas associated with attention, planning, and self-reflection. Where less sensitive individuals might process stimuli quickly and move on, the HSP brain lingers, comparing new information against existing knowledge, considering implications, and generating more elaborate mental representations.

Elaine Aron’s 2012 review in Personality and Social Psychology Review synthesized evidence showing that depth of processing represents a core feature of sensory processing sensitivity. This processing style influences everything from decision making to creative thinking to social relationships. Sensitive individuals naturally consider multiple perspectives and potential outcomes, which can appear as indecisiveness but actually reflects thorough analysis.

Throughout my marketing career, this depth of processing proved invaluable for strategic planning. When reviewing campaign concepts, I could quickly identify potential problems or opportunities that others missed on first review. Client presentations required extra preparation because I would anticipate questions and objections that more spontaneous colleagues never considered. The same cognitive style that created challenges in fast-paced brainstorming sessions became a significant advantage in strategic development.

The Pause to Check Response

A distinctive behavioral pattern in highly sensitive individuals is what researchers call the pause to check response. Before entering novel situations, sensitive people tend to hang back, observe, and gather information. This behavior reflects underlying neural processes that prioritize thorough assessment over rapid action. Brain regions involved in executive function and risk assessment show enhanced engagement during these observational periods.

This tendency can be misinterpreted as shyness, social anxiety, or lack of confidence. In reality, the pause to check serves an important adaptive function. By gathering information before acting, sensitive individuals frequently make better initial decisions and avoid errors that more impulsive peers might make. The strategy proved advantageous in our evolutionary past and continues to offer benefits in modern contexts requiring careful judgment.

Managing Fortune 500 client accounts taught me to leverage this instinct instead of fighting against it. New client relationships always involved an observation period where I would absorb communication styles, organizational dynamics, and unspoken expectations. Colleagues who jumped in immediately sometimes made faster initial progress, but my more measured approach built stronger long-term relationships built on genuine awareness of client needs and preferences.

Distinguishing HSP From Clinical Conditions

Brain research has been crucial in distinguishing sensory processing sensitivity from clinical conditions that share superficial similarities. Conditions like autism spectrum disorder, PTSD, and schizophrenia can all involve heightened sensitivity to stimuli, leading to potential confusion. Neuroimaging studies reveal fundamentally different patterns of brain activation, particularly in regions governing empathy and social cognition.

Highly sensitive individuals show enhanced activation in empathy-related brain regions, contrasting sharply with the reduced social cognition observed in autism spectrum disorder. Similarly, while PTSD involves hypervigilance and sensory reactivity, the underlying neural mechanisms differ substantially from those observed in trait sensitivity. Recognizing these distinctions helps researchers and clinicians alike provide appropriate support without pathologizing a normal variation in human temperament.

The question of whether HSP should be classified as neurodivergent remains actively debated. What seems clear is that sensitivity represents a normal trait found across species, associated with both costs and benefits depending on environmental context. Viewing it as a disorder to be treated misses the scientific evidence as well as the lived experiences of sensitive individuals who thrive when properly supported.

Practical Applications of HSP Brain Science

Grasping the neuroscience of sensitivity offers practical insights for managing daily life. Knowledge that your brain processes sensory and emotional information more deeply explains why overstimulation occurs and suggests environmental modifications that can help. Creating low-stimulation spaces, scheduling recovery time after intense social interactions, and choosing work environments that match your processing style all become easier to justify when backed by brain research.

For leaders and managers, awareness of sensitivity as a neurological trait can transform team dynamics. Sensitive team members may need quieter workspaces, advance notice of changes, and more processing time for decisions. They also bring enhanced perceptiveness, deeper thinking, and stronger empathy that benefit team performance when properly supported. Distinguishing the scientific understanding from popular oversimplifications helps create genuinely supportive workplace cultures.

The differential susceptibility framework suggests that investing in positive environments for sensitive individuals yields outsized returns. Therapy, coaching, and supportive relationships may be particularly effective for highly sensitive people precisely because their brains absorb beneficial influences more thoroughly. This insight has significant implications for treatment approaches, educational strategies, and workplace design.

The Future of Sensitivity Research

Neuroscience research on sensory processing sensitivity continues to expand, with new studies examining neural connectivity patterns, developmental trajectories, and interactions between genetic and environmental factors. Advances in imaging technology allow increasingly precise mapping of brain function, promising deeper insight into how sensitive brains develop and operate throughout the lifespan.

Emerging research explores how sensitivity interacts with specific life experiences, cultural contexts, and support systems. Questions about whether sensitivity can be modified through intervention, how best to support sensitive children’s development, and what workplace accommodations prove most effective for sensitive adults all represent active areas of investigation. The scientific foundation established over the past three decades provides solid ground for this ongoing work.

For those of us living with highly sensitive brains, the accumulating research validates experiences we have always known were real. Our nervous systems genuinely process information differently. The depth we feel, the awareness we carry, the empathy that sometimes overwhelms us, all have measurable neurological correlates. Far from being weaknesses requiring correction, these brain differences represent a distinct way of engaging with the world that has persisted throughout human evolution for good reason.

Explore more HSP science and support resources in our complete HSP & Highly Sensitive Person Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.

Frequently Asked Questions

What brain regions are most active in highly sensitive people?

Research using fMRI technology has identified several brain regions that show enhanced activation in highly sensitive individuals. The anterior insula, which processes interoceptive awareness and emotional states, shows particularly strong activity. The cingulate cortex, prefrontal regions involved in attention and planning, and areas associated with mirror neuron function also demonstrate heightened responsiveness. These regions work together to support the deep processing, empathy, and environmental awareness characteristic of high sensitivity.

Is high sensitivity genetic or learned?

High sensitivity has a substantial genetic component. Research has linked the trait to variations in genes regulating serotonin and dopamine neurotransmitter systems. The 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter gene variant and dopamine D4 receptor gene variations have both been associated with heightened sensitivity. Twin studies confirm significant heritability, meaning sensitivity tends to run in families. Environmental factors can influence how the trait manifests, but the underlying predisposition appears to be largely innate.

How does the HSP brain differ from autism?

High sensitivity and autism spectrum disorder can appear similar on the surface due to shared features like sensory reactivity, but brain research reveals fundamental differences. Highly sensitive individuals show enhanced activation in empathy and social cognition regions, particularly when viewing emotional expressions. Autism spectrum disorder involves reduced function in these same regions. The underlying neurology is essentially opposite, with HSPs showing heightened social processing while ASD involves differences in social cognition circuits.

What is differential susceptibility in HSP research?

Differential susceptibility is a framework that views sensitivity as amplification rather than vulnerability. Highly sensitive individuals respond more intensely to all environmental influences, both negative and positive. In adverse conditions, sensitivity may increase risk for problems. In supportive environments, sensitive individuals often thrive beyond their less sensitive peers. This bidirectional susceptibility represents an evolutionary strategy that persists because it offers advantages in certain contexts.

Can brain-based interventions help highly sensitive people?

The differential susceptibility framework suggests that highly sensitive people may respond particularly well to positive interventions. Their brains appear to absorb beneficial influences more deeply, making therapy, supportive relationships, and skill-building programs potentially more effective. Environmental modifications that reduce overstimulation can help sensitive brains function optimally. Understanding the neurological basis of sensitivity helps clinicians and coaches tailor approaches that work with rather than against how the HSP brain operates.