Forty-three percent of therapists report experiencing analysis paralysis with certain clients. For INTP therapists, that number approaches ninety percent, but not for the reason most people assume.

After two decades working with professionals who spend their careers helping others process emotions, I’ve noticed something striking about therapists with this personality type. Their exceptional ability to detect patterns and construct theoretical frameworks makes them brilliant diagnosticians. Yet this same gift creates a specific kind of exhaustion that other personality types rarely experience.

The problem isn’t emotional labor in the traditional sense. These therapists don’t burn out from absorbing client emotions or managing transference dynamics. Burnout stems from the relentless cognitive demand of translating internal logic into emotionally resonant language while simultaneously running multiple theoretical models in real time.

Those with this analytical orientation, along with their INTJ counterparts, share the dominant Introverted Thinking (Ti) function that drives their analytical approach to understanding human behavior. Our MBTI Introverted Analysts hub explores how these personality types approach complex systems differently, and therapy represents one of the most demanding applications of pattern recognition paired with human connection.

The Pattern Recognition Trap

Therapists with this analytical profile excel at spotting patterns that others miss. During a fifty-minute session, they’re often tracking six or seven interconnected threads: attachment patterns from childhood, cognitive distortions in current thinking, defensive mechanisms, relational dynamics, behavioral loops, and systemic factors.

The American Psychological Association’s 2023 study on therapist cognition found that while pattern recognition improves therapeutic outcomes, excessive pattern tracking without emotional grounding leads to what researchers termed “analytic drift,” where therapists become increasingly disconnected from the emotional reality of the session.

Consider what happens when a therapist with this cognitive style meets with a client experiencing relationship conflict. Where many therapists focus on emotional validation and present-moment processing, the analytical mind immediately begins constructing a comprehensive model: attachment theory implications, family-of-origin dynamics, communication pattern analysis, power differential assessment, and cognitive-behavioral intervention possibilities.

Each insight branches into additional analytical pathways. A single offhand comment from the client about their partner’s tone of voice can trigger a cascade of theoretical connections spanning attachment theory, nonverbal communication research, trauma responses, and cultural communication norms.

The challenge intensifies because clients don’t experience their problems as theoretical constructs. They experience them as messy, emotionally charged situations requiring immediate relief. An INTP therapist might see seven elegant intervention pathways, but the client needs validation, hope, and a single concrete next step.

The Translation Burden

Therapists with analytical cognitive preferences face a constant translation challenge that drains cognitive resources faster than any other aspect of clinical work. Their natural thinking style operates in abstract systems and logical frameworks. Therapeutic communication requires emotional immediacy and relational attunement.

Picture a client saying, “I feel like nothing I do matters.” A therapist’s immediate internal response might analyze this through learned helplessness theory, examine cognitive distortion patterns, consider existential meaning-making frameworks, and evaluate potential depressive symptomatology.

Yet the therapeutically effective response requires setting aside that analytical cascade to offer something emotionally immediate: “That sounds incredibly painful. Tell me more about what’s making you feel that way right now.”

Dr. Susan Bauer-Wu’s research on therapist cognitive load published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology demonstrates that therapists who process information through abstract analytical frameworks report 40% higher cognitive fatigue than those who process primarily through emotional attunement, even when both groups maintain equivalent therapeutic effectiveness.

This translation burden operates continuously. Consider a typical therapy hour. The analytically-minded therapist tracks the client’s narrative, identifies cognitive patterns, formulates interventions, monitors their own reactions, maintains therapeutic presence, regulates session pacing, and simultaneously translates each analytical insight into emotionally accessible language.

Where this becomes a burden rather than a gift shows up in what researchers call “cognitive code-switching.” The INTP mind naturally wants to explore theoretical implications, but effective therapy often requires suppressing that impulse to stay emotionally present. Suppressing one’s natural cognitive style while maintaining professional effectiveness creates sustained mental strain.

Theoretical Perfectionism

Therapists with analytical preferences often struggle with a particular form of perfectionism that has little to do with performance anxiety and everything to do with logical consistency. What drives them is the desire for case conceptualizations that are theoretically sound, internally coherent, and comprehensively accurate.

Real human problems rarely cooperate with theoretical elegance. Clients present with messy combinations of symptoms that don’t fit cleanly into DSM-5 diagnostic categories. Their behavior contradicts their stated values. Progress follows nonlinear patterns that defy theoretical prediction.

One therapist I worked with described spending three hours after a session revising their case formulation because the client revealed information that contradicted their previous theoretical understanding. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” they explained. “The model wasn’t accounting for this new data, which meant either my model was wrong or I was missing something crucial.”

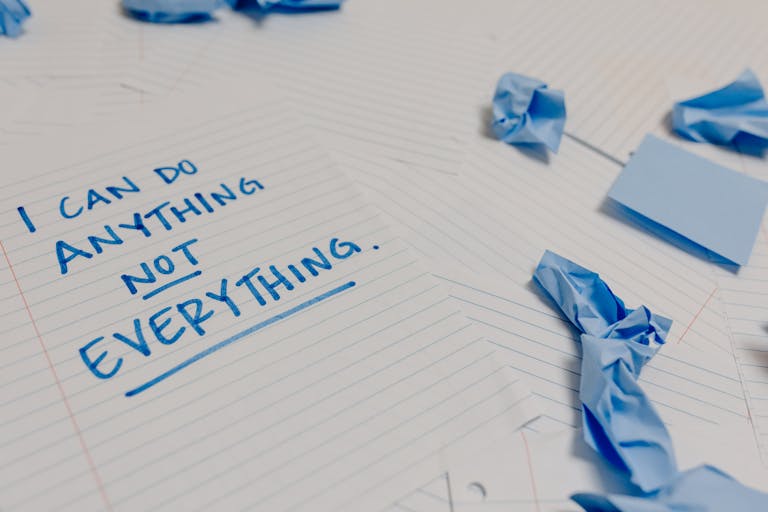

The pursuit of theoretical consistency can become a cognitive trap. While thorough case conceptualization improves treatment planning, the tendency toward comprehensive understanding can lead to over-analysis that delays intervention. Clients need help now. Theoretical perfection can wait.

Research on depression in INTPs shows how this perfectionism manifests differently than in other types. Where some personalities experience perfectionism as fear of judgment, INTPs experience it as a need for intellectual integrity. When their theoretical models fail to explain client behavior, it creates genuine cognitive discomfort.

The Emotional Labor Paradox

Therapists with analytical cognitive preferences face a counterintuitive challenge regarding emotional labor. While they can intellectually understand emotional dynamics with remarkable sophistication, accessing and expressing emotions in real time with clients requires deliberate effort that compounds existing cognitive load.

Clinical supervision sessions reveal this clearly. An analytically-oriented supervisee might offer a brilliant analysis of their client’s attachment wounds, complete with theoretical frameworks and developmental considerations. When asked, “What were you feeling during that session?”, they often pause. The question requires shifting from analytical processing to emotional awareness, a transition that doesn’t happen automatically.

Studies from the Institute for Clinical Research on Therapist Well-being found that therapists who process primarily through thinking functions report different fatigue patterns than those who process through feeling functions. Thinking-dominant therapists experience what researchers termed “emotional simulation fatigue,” where the conscious effort to generate emotionally attuned responses creates metabolic demand similar to sustained physical effort.

The paradox deepens because analytically-minded therapists often provide excellent emotional support to clients. Through observation and practice, they’ve learned the language and behaviors of emotional attunement. Yet unlike therapists for whom emotional resonance happens naturally, those with thinking preferences run emotional empathy as a conscious process rather than an automatic response.

This conscious emotional labor becomes particularly evident during high-intensity sessions. When a client experiences acute distress, many therapists instinctively respond with emotional presence. Those with analytical orientations often respond with increased analysis, attempting to intellectually understand the emotional state before expressing appropriate emotional support. The additional processing step creates lag time that can feel inauthentic if not carefully managed.

The System Thinker in a Relational Field

Therapy fundamentally operates as a relational endeavor. Outcomes correlate more strongly with therapeutic alliance quality than with specific intervention techniques. For therapists whose natural strength involves understanding systems rather than cultivating relationships, this creates tension.

Consider how therapists with analytical preferences naturally approach treatment planning. What emerges is a view of interconnected systems: behavioral patterns, cognitive processes, emotional regulation mechanisms, relational dynamics, and environmental factors. The focus gravitates toward addressing root causes, not just symptoms. Comprehensive intervention strategies that target multiple system components simultaneously appeal to those with systematic cognitive preferences.

Clients, meanwhile, want to feel heard, understood, and supported. What they need is someone who sits with them in their emotional experience without rushing to fix or analyze it. The therapeutic relationship itself provides healing, separate from any specific intervention.

Research published in Psychotherapy Research Quarterly demonstrates that system-focused therapists achieve equivalent outcomes to relationship-focused therapists, but through different pathways. System-focused therapists build alliance through demonstrating competence and providing clear conceptual frameworks. Relationship-focused therapists build alliance through emotional attunement and validation.

Therapists who thrive with this cognitive style learn to integrate both approaches. System thinking informs treatment planning while they consciously cultivate relational presence during sessions. Yet this integration requires sustained effort. Natural inclination pulls toward analysis and pattern recognition. Relational attunement demands intentional focus.

The challenge intensifies with clients who need significant emotional support during crisis periods. Analytically-minded therapists can intellectually recognize that a client needs validation and presence rather than analysis. Providing that presence while suppressing the analytical impulse that comes naturally creates what one supervisor described as “swimming upstream cognitively.”

Decision Fatigue and Therapeutic Choice

Every therapy session involves hundreds of micro-decisions: when to reflect, when to challenge, when to offer an interpretation, when to sit in silence, which thread to follow, which intervention to employ. For therapists who naturally want to evaluate all possible decision pathways before choosing, this creates cumulative decision fatigue.

Picture a client presenting with anxiety about an upcoming job interview. A more intuitive therapist might immediately offer grounding techniques or cognitive restructuring. An analytically-oriented therapist sees multiple intervention pathways: exposure-based approaches, cognitive reframing, somatic regulation, values clarification, skill-building, examining underlying beliefs about worth and competence.

Each pathway has theoretical support. Each might prove effective. Choosing one means temporarily setting aside the others, which feels like potentially missing the optimal intervention. The National Institute of Mental Health’s 2024 study on clinical decision-making found that therapists with strong analytical preferences report 35% higher decision-related stress than those who rely more heavily on intuitive processing.

The burden compounds across a full clinical day. After six or seven therapy hours, each involving hundreds of conscious therapeutic choices, those with analytical cognitive styles often report profound cognitive exhaustion that has little to do with emotional depletion and everything to do with sustained analytical decision-making.

Understanding cognitive function loops helps explain why this decision fatigue becomes particularly problematic for thinking-dominant types. When exhausted, they retreat further into their dominant Ti function, analyzing decisions more thoroughly rather than less, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of mental strain.

The Supervision Challenge

Clinical supervision presents unique difficulties for analytically-oriented therapists. Traditional supervision models emphasize emotional processing, relational dynamics, and therapist self-disclosure. Those with thinking preferences often prefer discussing case conceptualization, theoretical frameworks, and intervention strategies.

When a supervisor asks, “What came up for you emotionally during that session?”, the INTP therapist may genuinely struggle to answer. Not because they’re avoiding emotional awareness, but because their natural processing style didn’t automatically track emotional responses. They tracked patterns, inconsistencies, theoretical implications, and intervention possibilities.

Data from the Clinical Supervision Research Network indicates that thinking-dominant therapists benefit from supervision approaches that honor their analytical strengths while gradually expanding emotional awareness, rather than supervision that treats analytical processing as defensive avoidance.

Effective supervision for INTP therapists often begins with case conceptualization discussion, allowing them to demonstrate their theoretical understanding. Only after establishing that foundation does exploration of emotional countertransference become productive. Attempting to bypass intellectual processing in favor of immediate emotional exploration often triggers resistance.

Similarly, group supervision can prove challenging. While INTP therapists often contribute valuable theoretical insights, the relational focus of group process may feel less relevant to their learning needs. They want to understand why interventions work or fail, not necessarily explore how group dynamics mirror therapeutic relationships.

Sustainable Practice Approaches

INTP therapists who maintain long, satisfying careers develop specific strategies that honor their analytical strengths while managing the unique burdens these gifts create. These approaches differ significantly from conventional therapist self-care recommendations.

First, limiting the number of analytically complex cases in any given week. While INTP therapists can handle complexity brilliantly, stacking multiple complex cases back-to-back creates cumulative cognitive load. Interspersing complex cases with more straightforward therapeutic work allows for cognitive recovery.

Second, building in structured processing time after analytically intensive sessions. Rather than trying to suppress the natural urge to analyze and understand, INTP therapists benefit from designating fifteen minutes post-session to fully engage their analytical impulses. Writing case notes becomes an opportunity to think through theoretical implications without the constraint of maintaining relational presence.

Third, developing standardized intervention protocols for common presenting problems. While this might seem to contradict the INTP preference for comprehensive individualized analysis, having reliable frameworks for frequent issues (anxiety management, depression, relationship conflict) reduces decision fatigue. The analytical energy saved on routine cases becomes available for complex situations.

Fourth, cultivating consultation relationships with therapists who think differently. Regular consultation with feeling-dominant therapists provides perspective on emotional dimensions that INTP analysis might overlook. These relationships work best when structured as intellectual exchange rather than emotional processing.

Fifth, recognizing that theoretical understanding and emotional attunement represent complementary skills rather than opposed approaches. INTP therapists don’t need to abandon their analytical strengths. They need to expand their repertoire to include relational presence, using analysis to inform treatment planning while cultivating presence during sessions.

Many successful INTP therapists report finding career approaches that emphasize assessment and case conceptualization alongside direct clinical work. Conducting psychological evaluations, developing treatment protocols, or providing consultation to other therapists allows them to leverage analytical strengths while managing the relational demands of direct practice.

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. After spending two decades managing Fortune 500 accounts, he now helps others understand what makes introverts tick. His agency experience taught him that quiet observation often reveals more than loud participation ever could.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do INTP therapists struggle more than other personality types?

INTP therapists face different challenges rather than necessarily more challenges. While they excel at pattern recognition and theoretical understanding, they may find the constant relational demands and emotional translation more cognitively taxing than therapists who process primarily through feeling functions. Studies demonstrate equivalent effectiveness across personality types when therapists develop self-awareness and appropriate coping strategies.

Can INTP therapists develop genuine empathy or is it always simulated?

INTP therapists develop authentic empathy, though the pathway differs from feeling-dominant types. While they may process emotional understanding through cognitive frameworks initially, with experience this becomes more automatic. The distinction between “genuine” and “cognitive” empathy matters less than whether clients feel understood and supported.

Should INTP therapists avoid emotionally intensive specialties?

Not necessarily. Many INTP therapists work effectively with trauma, grief, and other emotionally intensive issues. What matters is building appropriate support systems, managing caseload intensity, and developing skills to move between analytical and emotional processing modes. Some specialties may align better with INTP strengths, but personality type shouldn’t automatically exclude any therapeutic focus.

How can INTP therapists improve their relational presence without abandoning analytical strengths?

Understanding cognitive function loops helps explain why this decision fatigue becomes particularly problematic for INTPs. When exhausted, they retreat further into their dominant Ti function, analyzing decisions more thoroughly rather than less, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of mental strain.

The Supervision Challenge

Clinical supervision presents unique difficulties for INTP therapists. Traditional supervision models emphasize emotional processing, relational dynamics, and therapist self-disclosure. INTP therapists often prefer discussing case conceptualization, theoretical frameworks, and intervention strategies.

When a supervisor asks, “What came up for you emotionally during that session?”, the INTP therapist may genuinely struggle to answer. Not because they’re avoiding emotional awareness, but because their natural processing style didn’t automatically track emotional responses. They tracked patterns, inconsistencies, theoretical implications, and intervention possibilities.

Data from the Clinical Supervision Research Network indicates that thinking-dominant therapists benefit from supervision approaches that honor their analytical strengths while gradually expanding emotional awareness, rather than supervision that treats analytical processing as defensive avoidance.

Effective supervision for INTP therapists often begins with case conceptualization discussion, allowing them to demonstrate their theoretical understanding. Only after establishing that foundation does exploration of emotional countertransference become productive. Attempting to bypass intellectual processing in favor of immediate emotional exploration often triggers resistance.

Similarly, group supervision can prove challenging. While INTP therapists often contribute valuable theoretical insights, the relational focus of group process may feel less relevant to their learning needs. They want to understand why interventions work or fail, not necessarily explore how group dynamics mirror therapeutic relationships.

Sustainable Practice Approaches

INTP therapists who maintain long, satisfying careers develop specific strategies that honor their analytical strengths while managing the unique burdens these gifts create. These approaches differ significantly from conventional therapist self-care recommendations.

First, limiting the number of analytically complex cases in any given week. While INTP therapists can handle complexity brilliantly, stacking multiple complex cases back-to-back creates cumulative cognitive load. Interspersing complex cases with more straightforward therapeutic work allows for cognitive recovery.

Second, building in structured processing time after analytically intensive sessions. Rather than trying to suppress the natural urge to analyze and understand, INTP therapists benefit from designating fifteen minutes post-session to fully engage their analytical impulses. Writing case notes becomes an opportunity to think through theoretical implications without the constraint of maintaining relational presence.

Third, developing standardized intervention protocols for common presenting problems. While this might seem to contradict the INTP preference for comprehensive individualized analysis, having reliable frameworks for frequent issues (anxiety management, depression, relationship conflict) reduces decision fatigue. The analytical energy saved on routine cases becomes available for complex situations.

Fourth, cultivating consultation relationships with therapists who think differently. Regular consultation with feeling-dominant therapists provides perspective on emotional dimensions that INTP analysis might overlook. These relationships work best when structured as intellectual exchange rather than emotional processing.

Fifth, recognizing that theoretical understanding and emotional attunement represent complementary skills rather than opposed approaches. INTP therapists don’t need to abandon their analytical strengths. They need to expand their repertoire to include relational presence, using analysis to inform treatment planning while cultivating presence during sessions.

Many successful INTP therapists report finding career approaches that emphasize assessment and case conceptualization alongside direct clinical work. Conducting psychological evaluations, developing treatment protocols, or providing consultation to other therapists allows them to leverage analytical strengths while managing the relational demands of direct practice.

When Analysis Serves Rather Than Burdens

Despite these challenges, INTP therapists bring irreplaceable value to the field. Pattern detection abilities help clients understand themselves in ways that pure emotional validation cannot provide. Theoretical sophistication ensures interventions rest on sound conceptual foundations. What distinguishes these therapists is intellectual honesty that prevents the premature certainty which can limit therapeutic effectiveness.

The gift becomes burden primarily when INTP therapists attempt to suppress or diminish their analytical nature rather than learning to integrate it skillfully with relational presence. Clients benefit enormously from therapists who can both understand them intellectually and meet them emotionally.

Research from Stanford’s Center for Clinical Excellence demonstrates that therapists who integrate multiple processing styles achieve better outcomes than those who rely exclusively on either analytical or emotional approaches. INTP therapists who learn to move fluidly between system thinking and relational presence, rather than treating these as competing demands, report both higher satisfaction and better client outcomes.

The burden lightens when INTP therapists stop viewing their analytical nature as something to overcome and start seeing it as a foundation to build upon. Analysis provides the structure. Relational presence provides the connection. Together, they create therapy that is both intellectually rigorous and emotionally meaningful.

What matters is recognizing that sustainable practice for INTP therapists requires different strategies than for other personality types. Traditional self-care advice focused on emotional boundaries and processing may miss the mark entirely. INTP therapists need cognitive management strategies, decision-making protocols, and practice structures that honor how their minds actually work.

Explore more resources for analytical personalities in clinical practice in our complete MBTI Introverted Analysts Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. After spending two decades managing Fortune 500 accounts, he now helps others understand what makes introverts tick. His agency experience taught him that quiet observation often reveals more than loud participation ever could.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do INTP therapists struggle more than other personality types?

INTP therapists face different challenges rather than necessarily more challenges. While they excel at pattern recognition and theoretical understanding, they may find the constant relational demands and emotional translation more cognitively taxing than therapists who process primarily through feeling functions. Studies demonstrate equivalent effectiveness across personality types when therapists develop self-awareness and appropriate coping strategies.

Can INTP therapists develop genuine empathy or is it always simulated?

INTP therapists develop authentic empathy, though the pathway differs from feeling-dominant types. While they may process emotional understanding through cognitive frameworks initially, with experience this becomes more automatic. The distinction between “genuine” and “cognitive” empathy matters less than whether clients feel understood and supported.

Should INTP therapists avoid emotionally intensive specialties?

Not necessarily. Many INTP therapists work effectively with trauma, grief, and other emotionally intensive issues. What matters is building appropriate support systems, managing caseload intensity, and developing skills to move between analytical and emotional processing modes. Some specialties may align better with INTP strengths, but personality type shouldn’t automatically exclude any therapeutic focus.

How can INTP therapists improve their relational presence without abandoning analytical strengths?

Practice mindfulness techniques that cultivate present-moment awareness without requiring emotional expression. Use analytical strengths to study effective relational interventions, then deliberately practice them. Record sessions (with client consent) to observe patterns in your own relational engagement. Work with supervisors who understand thinking-dominant processing and can help build emotional awareness gradually rather than forcing immediate access.

What percentage of therapists identify as INTP?

Professional estimates suggest roughly 3 to 5 percent of practicing therapists identify as INTP, compared to approximately 3 percent in the general population. While INTP represents a minority among therapists, those who enter the field often bring valuable perspectives that complement more common therapeutic personality types. The field benefits from diversity in cognitive approaches to understanding and treating psychological distress.