The acceptance letter arrives in April. Move-in day shows up by August. Between those two dates, incoming students imagine dorm life as movie montages of late-night conversations, instant friendships, and the freedom to reinvent themselves. Few anticipate that college might be the first time they’re never alone.

Campus housing operates on a different frequency. Hallways buzz at midnight. Communal bathrooms never close. Doors stay propped open as unspoken invitations to interrupt. For students who recharge in solitude, this constant availability creates a challenge most orientation programs never mention: how to preserve yourself when privacy becomes a privilege.

After years of leading large marketing teams, I recognize the difference between necessary social interaction and what drains your reserves without adding value. Those back-to-back meetings I scheduled? They extracted energy from everyone, but some team members recovered during their commute home. Others needed three hours of silence just to reach baseline again. The distinction matters when you’re sharing 12×14 feet with someone who may never leave.

The Dorm Reality Nobody Discusses

Research from the University of Northern Iowa examined mental well-being among introverted college students. The study found that individuals who need internal processing time face particular challenges in environments designed for constant social engagement. Shared living spaces eliminate the natural buffer most people use to regulate their energy.

Consider the typical freshman housing arrangement. Most colleges assign double or triple occupancy rooms. You share a bathroom with 20-30 other students. Common areas feature perpetual foot traffic. Fire codes prohibit locks on bedroom doors beyond the standard key. The architecture assumes everyone benefits equally from proximity. Understanding how different personality types function in shared environments helps explain why some students adapt quickly as others struggle.

Your roommate might thrive on midnight conversations and spontaneous floor gatherings. You might need silence to process the day’s classes. Neither preference indicates a problem. The friction emerges when physical space can’t accommodate both needs simultaneously.

Roommate Dynamics and Energy Management

According to Harvard Summer School’s residential life guidelines, successful dorm living requires establishing boundaries within the first two weeks. This timeline makes sense for addressing logistical questions about cleaning schedules and guest policies. It misses the deeper challenge of explaining that you’re not antisocial when you need three hours alone after classes.

The conversation feels awkward because campus culture celebrates constant connection. Someone who closes their door sends a visible signal that contradicts the assumed enthusiasm for community. You risk being labeled unfriendly before anyone understands you’re simply managing your capacity.

Setting Boundaries Without Alienating Roommates

Start by acknowledging the difference between isolation and recharging. Isolation stems from avoidance or disconnection. Recharging is a deliberate choice to restore your baseline so you can engage meaningfully later. Frame your needs in terms of what enables you to show up as your best self.

Try these specific strategies:

Propose a shared calendar system. Mark your study blocks and solo time visually so your roommate sees patterns without interpreting them as rejection. When they know Thursday afternoons mean you need quiet, they can plan accordingly.

Explain your social capacity using concrete examples. Instead of saying “I need alone time,” describe how you operate: “I can handle about four hours of group activities before I need to reset. That’s just how I’m wired.”

Create visible signals that communicate your availability. A closed door with headphones means deep focus. An open door suggests you’re open to brief conversations. These visual cues prevent the need for repeated verbal explanations.

When Incompatibility Isn’t Personal

The JED Foundation’s mental health resources note that roommate conflicts often stem from mismatched living styles. Someone who sees the dorm as a base camp for social activities will clash with someone who treats it as a sanctuary. Neither approach is wrong. The space simply can’t accommodate both simultaneously.

During my agency years, I observed this pattern in office layouts. Open floor plans boosted collaboration for some employees. Others experienced performance drops from the constant stimulation. We solved it by creating designated quiet zones and flexible work schedules. Dorm life rarely offers that luxury.

If conversations and compromises fail, switching rooms isn’t defeat. It’s practical problem-solving. Most residential life offices facilitate changes after the first few weeks once patterns become clear. Advocate for your needs directly with your Resident Advisor before resentment builds.

Social Pressure and Campus Expectations

U.S. News research on introverted college students found that campus social structures favor those who gain energy from interaction. Orientation activities emphasize meeting everyone quickly. Student organizations reward visible participation. Even academic success increasingly depends on group projects and class discussions.

The underlying message suggests that thriving in college means filling every moment with connection. Missing floor dinners or skipping parties gets interpreted as missing out. This framing ignores that meaningful engagement looks different for different people.

Quality Over Quantity in Friendships

Studies from Frontiers in Psychology examining social engagement and self-esteem revealed that introverted students with meaningful social connections reported higher well-being than those with large but superficial networks. The research challenges the assumption that more social interaction automatically improves college experience.

Focus on depth instead of breadth. Three genuine friendships provide more support than thirty acquaintances you recognize in dining halls. Look for people who respect your need for downtime and whose company doesn’t drain your energy reserves.

Seek out smaller organizations that align with your interests. Club meetings with eight members allow for substantial conversation. Events with three hundred attendees force you into surface-level exchanges that may leave you depleted without building actual connection.

Declining Invitations Without Guilt

Campus culture treats saying no as social failure. Your floor plans a movie night every Friday. Your study group wants to meet Sunday mornings. The student organization schedules weekly happy hours. Accepting every invitation to prove you’re social enough leads directly to burnout.

Practice selective participation. Attend the events that genuinely interest you. Decline the ones that feel like obligations. Brief explanations work better than elaborate justifications: “Thanks for inviting me, but I have other plans tonight.”

Those other plans might be reading alone in your room. That counts as a valid choice. You’re not obligated to perform enthusiasm for activities that drain rather than energize you.

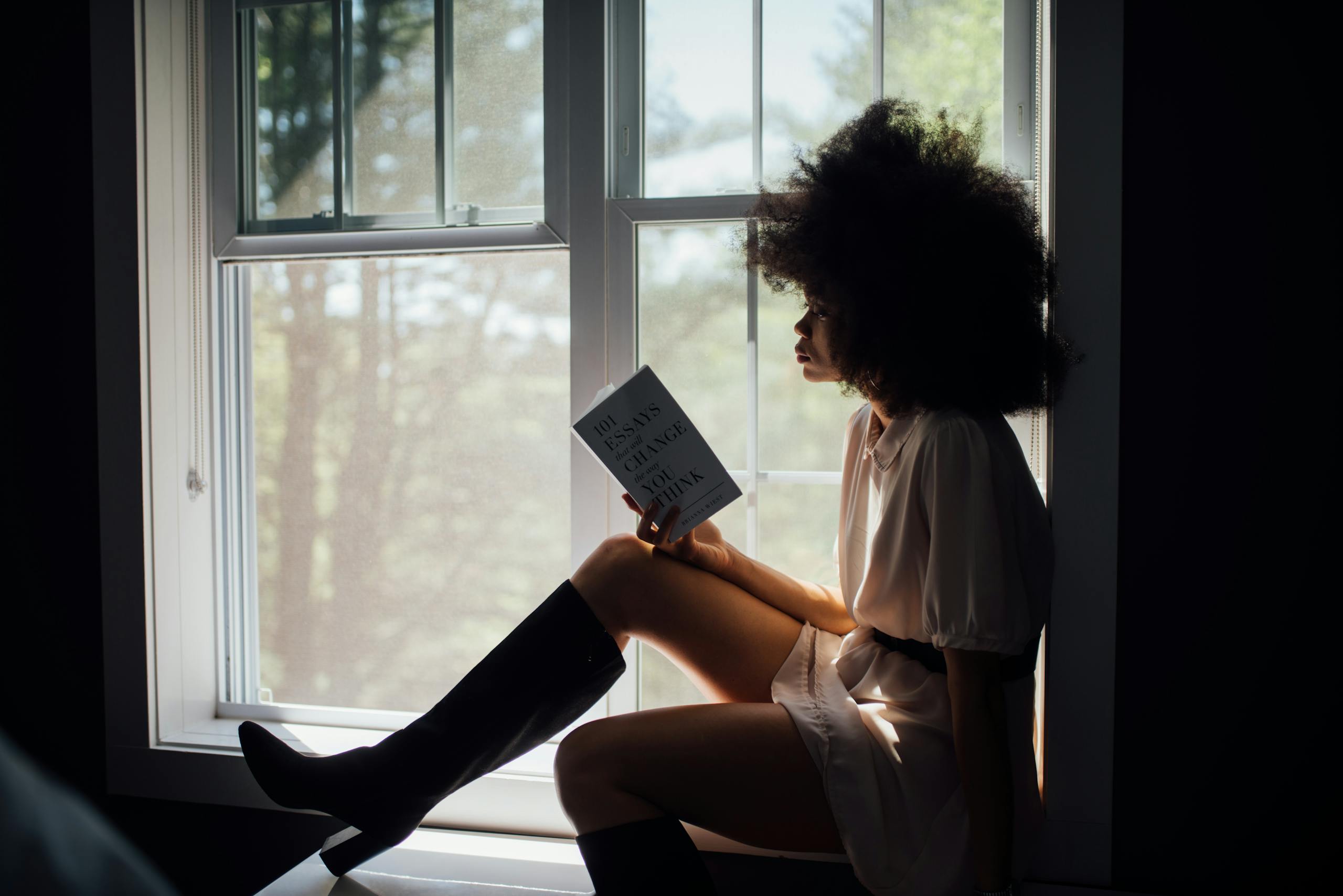

Finding Your Quiet Spaces on Campus

Every campus contains pockets of solitude if you know where to look. Upper floors of libraries stay emptier than main reading rooms. Academic buildings feature unused classrooms between class periods. Outdoor spaces offer benches tucked away from main pathways. Map these locations during your first few weeks.

According to Fastweb’s guide to freshman dorm life, students who establish retreat spaces report better adjustment to campus life. These locations become essential when your dorm room can’t provide the quiet you need.

Strategic Use of Campus Resources

Visit the library during non-peak hours. Early mornings and late afternoons see less traffic than evenings when everyone studies for exams. Graduate reading rooms may allow undergraduate access and typically stay quieter than freshman study areas.

Check if your campus maintains a meditation or reflection room. Many universities now offer these spaces specifically for students who need quiet. Some require reservations. Others operate on a drop-in basis.

Explore academic buildings outside your major. The engineering complex might house perfect study nooks if you’re studying literature. The arts building may offer peaceful corners if you’re in business school. Cross-discipline exploration reveals spaces other students overlook.

Balancing Academic Demands With Energy Limits

College academics reward certain behaviors that conflict with how many introverted students operate best. Participation grades incentivize frequent speaking regardless of whether comments add substance. Group projects assume everyone contributes equally in meetings. Office hours require initiating conversation with professors.

These structures aren’t inherently problematic. They create challenges when treated as the only path to success. My experience managing diverse teams taught me that valuable contributions come in many forms. The analyst who sent detailed written proposals often added more value than the person who dominated every brainstorming session.

Playing to Your Strengths Academically

Written assignments typically favor depth of analysis over speed of verbal response. Invest your energy in papers, projects, and exams where you can develop ideas thoroughly. Research from California State University found that introverted students often excel in written work and demonstrate stronger critical thinking in assignments that allow time for reflection. This advantage appears across fields, from literature to technical writing where thoughtful documentation outweighs meeting performance.

When participation counts toward your grade, focus on quality contributions instead of frequent ones. Prepare one or two substantive comments before class. Ask questions that advance the discussion. Professors notice students who add insight even if they don’t speak in every session.

For group projects, volunteer for roles that match your working style. Offer to handle research, writing, or analysis that you can complete independently. Let others take presentation responsibilities if public speaking drains you. Good teams distribute work according to strengths.

Office Hours as Strategic Advantage

Most students skip office hours despite professors encouraging attendance. This creates an opportunity. One-on-one conversations with professors allow for deeper academic discussion than classroom settings permit. You avoid competing for attention with more vocal classmates.

Prepare specific questions before attending. This structure makes conversations more productive and less awkward. Email ahead to schedule time if drop-in hours feel too chaotic. Many professors appreciate scheduled meetings since they can prepare more targeted guidance.

These individual interactions build relationships that lead to research opportunities, recommendation letters, and academic mentorship. The time investment pays dividends beyond any single course grade.

Creating Sanctuary in Shared Spaces

Your dorm room needs to function as both social space and private retreat. This dual purpose requires intentional design choices that most residence life guides overlook.

Physical Environment Modifications

Invest in quality noise-canceling headphones. This tool provides psychological privacy even when physical privacy isn’t available. Your roommate can have friends over as you create your own sound environment.

Use bed curtains or room dividers if your residence hall allows them. Visual privacy matters almost as much as acoustic privacy. Even a thin barrier signals when you need personal space.

Arrange your desk to face away from the door when possible. This positioning reduces the feeling of constant observation and creates a small psychological buffer.

Control lighting independently. String lights or desk lamps let you maintain softer illumination when overhead fluorescents feel too harsh. Environmental control contributes to feeling settled in your space.

Schedule Strategies for Alone Time

Track your roommate’s schedule during the first few weeks. Find patterns in their class times, work schedule, or regular activities. These gaps represent guaranteed solo time in your room.

Block these periods for activities that restore your energy. This might mean reading, napping, or simply existing without needing to interact. Protect this time as you would protect class schedules or work shifts.

Consider taking some classes at times your roommate doesn’t. Opposite schedules create natural separation that benefits everyone. You each gain time alone in your shared space without requiring difficult conversations about needing distance.

Mental Health and Knowing When to Seek Support

Adjustment challenges differ from ongoing mental health concerns. Feeling overwhelmed during the first month makes sense as you adapt to major life changes. Persistent feelings of isolation, anxiety, or depression require professional attention.

Research examining introversion and mental health found that personality type alone doesn’t predict psychological distress. Environmental factors, support systems, and stress management skills play larger roles. Campus counseling centers understand the distinction between adjustment difficulties and conditions requiring treatment.

Most colleges offer free or low-cost counseling services specifically for students. Initial appointments typically happen within a week or two. You’re not taking resources from someone who needs them more. These services exist precisely for students navigating challenging transitions.

Warning signs that suggest professional support would help include persistent sleep disruption beyond the first few weeks, inability to focus on coursework despite effort, avoiding all social contact including close friends, or recurring thoughts that college was a mistake.

Building Authentic Connections on Your Terms

Friendship in college doesn’t require attending every party or joining every group. The most meaningful connections often form in smaller contexts where depth of interaction matters more than breadth of exposure.

Look for structured activities with consistent membership. Weekly club meetings, academic study groups, or volunteer organizations create repeated contact with the same people. These settings allow relationships to develop gradually instead of forcing instant chemistry.

Shared interests provide natural conversation topics that bypass small talk. Discussing a book you both read or working together on a project removes the pressure of maintaining constant dialogue. The activity creates connection without requiring performance.

Quality friendships take time. Give yourself permission to build slowly instead of rushing to establish your social circle by October. The friends you make through genuine mutual interest will likely outlast the ones formed through proximity alone. Consider how even successful performers who struggle with constant public interaction prioritize authentic connections over widespread visibility.

Long-Term Strategies for Sustainable Success

Campus life doesn’t change to accommodate individual needs. You must actively create the conditions that let you thrive. This means treating energy management with the same seriousness you apply to time management.

Schedule recovery time as deliberately as you schedule classes. If Thursday includes four hours of group work, Friday afternoon needs to include solitude. This isn’t optional self-care. It’s maintenance that enables consistent performance.

Communicate your needs clearly without apologizing for them. You’re not asking permission to be yourself. You’re informing people how you operate so they can understand your choices. The right people will respect these boundaries. The ones who don’t probably weren’t compatible anyway. This direct communication skill serves you beyond college, from professional negotiations to personal relationships.

Recognize that freshman year represents adjustment, not permanent conditions. Most students gain housing flexibility as sophomores. You’ll have better understanding of campus resources. Your social circle will be more established. The initial overwhelm eventually gives way to sustainable rhythms.

Campus life challenges everyone differently. For students who recharge through solitude, dorm existence tests your ability to preserve yourself in spaces designed for constant connection. Success comes not from changing who you are but from building systems that protect what you need to function well. For comprehensive guidance on all aspects of introverted living, explore our complete resource library.

Explore more resources for navigating life as an introvert in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I explain to my roommate that I need alone time without offending them?

Frame your needs in terms of how you function best, not as a rejection of them. Explain that you need quiet time to recharge so you can be fully present during shared activities. Use concrete examples like “I need about two hours of solo time after classes to process the day.” This helps them understand your behavior as a personal requirement rather than a comment on the relationship.

Is it normal to feel overwhelmed by dorm life as an introvert?

Yes, many introverted students find the constant social availability of dorm life challenging. Research shows that individuals who recharge through solitude struggle more with shared living environments. The overwhelm you’re experiencing is a natural response to environmental conditions that don’t match your needs, not a sign that something is wrong with you or that you’re not “college material.”

What should I do if I can’t find quiet spaces on campus?

Explore campus buildings outside your usual areas, particularly upper floors of libraries, empty classrooms between class periods, and academic buildings in different departments. Visit at different times to identify less crowded periods. If your campus has a meditation room or wellness center, these often provide guaranteed quiet. Consider using noise-canceling headphones to create acoustic privacy even in busier environments.

How do I decline social invitations without damaging friendships?

Be honest but brief in your responses. Simple explanations like “Thanks for inviting me, but I need some downtime tonight” work better than elaborate justifications. Good friends will respect your boundaries. Occasionally suggest alternative one-on-one activities that feel more comfortable for you, which shows you value the friendship even when large group events drain you.

When should I consider switching roommates versus trying to make it work?

Try establishing clear boundaries and communication first. If repeated conversations fail to improve incompatible living styles, or if the situation negatively affects your academic performance or mental health, switching rooms becomes a practical solution. Most residential life offices facilitate changes after the first few weeks once patterns become clear. Prioritize your well-being over concerns about appearing difficult.