My inbox showed 23 unread messages at 7:42 AM on a Wednesday. Each one felt like a small cognitive claim on my attention. By the time I’d processed three of them, I’d already built complete mental models of what each person really meant beneath their words, tracked emotional subtexts they probably didn’t realize they were communicating, and noticed patterns in how their communication style had shifted since our last exchange.

That kind of processing happens automatically for me. It’s not something I choose to do.

After two decades of managing teams in high-pressure agency environments, I’ve come to see that the psychological differences between how my brain works and how my extroverted colleagues process the same information aren’t just about energy or social preference. The actual cognitive architecture operates on different principles. Where some people process stimuli quickly and move on, my brain constructs layered interpretive frameworks that continue running in the background long after the initial interaction ends.

The psychology of introversion extends far beyond simple definitions about recharging alone versus recharging with others. Your brain’s approach to information processing, emotional regulation, memory formation, and psychological resilience follows distinct patterns that show up in neuroscience research, cognitive psychology studies, and lived experience. Our General Introvert Life hub explores these patterns across different life contexts, and the psychological mechanics underneath them reveal something essential about how your mind actually works.

The Cognitive Processing Architecture

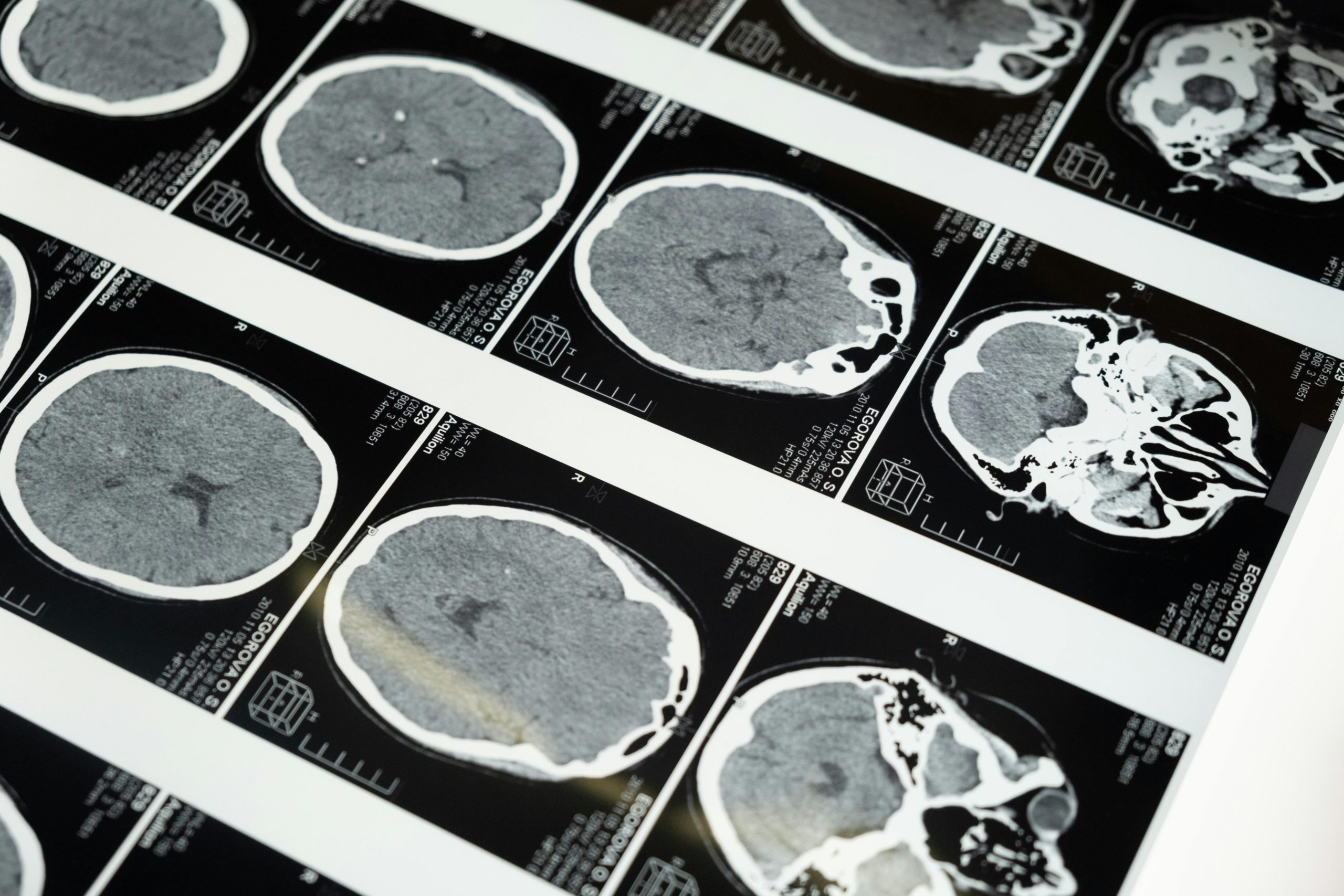

Neuroscientist Dr. Marti Olsen Laney’s research on brain pathways found that information travels through longer, more complex neural routes for individuals wired toward depth compared to extroverted processing patterns. The pathway involves the frontal lobe and anterior thalamus, regions associated with planning, problem-solving, and internal processing. It’s a different optimization strategy rather than a design flaw.

Think about how you respond to a complex question in a meeting. While others might offer immediate reactions, your brain automatically engages a multi-stage processing sequence. First comes perception, then internal analysis that draws on past experiences and theoretical frameworks, followed by emotional calibration, and finally verbal formulation. By the time you’re ready to speak, the conversation has often moved forward.

Slower processing speed doesn’t indicate lower intelligence. A 2012 study from the University of Pennsylvania revealed that individuals who showed activation in brain regions associated with internal mental processing demonstrated higher working memory capacity. The deliberate pace allows for more thorough analysis, better pattern recognition, and stronger logical consistency.

During one particularly intense client presentation, my team needed to pivot our entire strategy based on unexpected competitor moves. Everyone looked to me for direction. Instead of jumping to the obvious tactical response, I took fifteen seconds of silence that felt like fifteen minutes. That pause allowed me to process not just the surface problem but three layers of strategic implications my faster-processing colleagues had missed.

Emotional Depth and Psychological Sensitivity

Psychologist Elaine Aron’s research on sensory processing sensitivity found that approximately 70% of highly sensitive individuals identify as having this personality trait. The overlap isn’t coincidental. The psychological wiring processes emotional information with significantly more nuance and depth than average.

You don’t just feel emotions. You analyze them, track their origins, notice subtle variations in intensity, and observe how they interact with cognitive processes. Where someone else might experience anger as a simple reaction, you’re simultaneously aware of the anger, the trigger that caused it, the physical sensations accompanying it, the thoughts generating around it, and the behavioral impulses emerging from it.

A 2015 study in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience found that individuals with tendencies toward internal processing show greater activation in brain regions associated with empathy and self-awareness when viewing emotional images. The psychological makeup naturally attunes to emotional subtlety that others might overlook entirely.

One team member once told me she appreciated how I could sense when something was wrong before she’d articulated it herself. I’d noticed a slight shift in her communication cadence, a barely perceptible change in word choice, and an uncharacteristic brevity in her responses. These weren’t deliberate observations. My brain processes this information automatically, constructing psychological profiles of the people around me whether I want it to or not.

The Internal Workspace Model

Cognitive psychologists describe working memory as the mental space where active thinking occurs. For individuals wired for depth, this workspace operates more like a detailed simulation environment than a quick-access bulletin board. You’re not just holding information temporarily. You’re running complex scenarios, testing hypotheses, and building conceptual frameworks.

Research from Stanford University’s psychology department found that people who favor internal processing demonstrate enhanced ability to maintain and manipulate information in working memory compared to those who process externally through immediate verbalization. Your psychological architecture treats your internal workspace as the primary thinking environment rather than a temporary staging area.

Consider how you prepare for important conversations. You’re not just planning what to say. You’re mentally rehearsing different response pathways, anticipating emotional reactions, calibrating tone and phrasing, and running through potential outcomes. Internal preparation consumes significant cognitive resources but produces more thoughtful, coherent communication when you do speak.

After years of client negotiations, I learned to embrace rather than fight this internal preparation tendency. Where my extroverted colleagues could improvise brilliantly in real-time, I developed frameworks and mental models ahead of time that allowed me to access deep analysis without the appearance of hesitation. The psychological preparation became a strategic advantage rather than a limitation.

Memory Formation and Psychological Patterns

Your brain doesn’t just store memories differently. It encodes them with more contextual detail, emotional nuance, and associative connections. Psychological research on memory consolidation shows that individuals who process information deeply rather than superficially demonstrate superior long-term retention and more elaborate memory structures.

You remember not just what happened but how it felt, what you were thinking, what the environment was like, and how the experience connected to other experiences. A simple business lunch becomes a richly encoded memory that includes the conversation content, the emotional subtext, your internal reactions, the other person’s behavioral patterns, and observations about the setting itself.

Elaborate encoding explains why seemingly minor events can trigger powerful memories. A colleague using a particular phrase might activate an entire network of associated memories because your brain encoded not just the words but the psychological context surrounding them.

During performance reviews, I could often recall specific moments from months earlier with precise detail while my team members struggled to remember the same interactions. My psychological wiring automatically created detailed memory records that persisted long after the events themselves had passed. Understanding this pattern helped me realize I wasn’t being overly analytical. My brain simply processes and stores information at a different level of granularity.

Psychological Resilience Through Internal Resources

Research from the American Psychological Association indicates that individuals who demonstrate strong internal locus of control and capacity for self-reflection show enhanced psychological resilience during stress. Your natural tendency toward internal processing builds psychological resources that become protective factors during difficult periods.

You’re not dependent on external validation or constant social reinforcement to maintain psychological equilibrium. Your internal workspace provides a stable foundation that continues functioning even when external circumstances become chaotic. The ability to process experiences internally, extract meaning from difficult situations, and maintain psychological coherence without constant external input creates a different kind of resilience.

When my agency faced a major client loss that sent the extroverted team members into panic mode, I found myself processing the situation through internal analysis rather than external processing. I examined what went wrong, identified systemic issues rather than individual blame, and developed strategic responses. The psychological capacity for internal processing turned a crisis into a learning opportunity that strengthened rather than weakened the team.

The psychological patterns that define how your brain works aren’t flaws to correct. They’re sophisticated cognitive strategies optimized for depth, nuance, and internal coherence. Slower processing allows for more thorough analysis. Emotional sensitivity enables richer understanding. The internal workspace supports complex thinking. Detailed memory encoding preserves valuable information. Psychological resilience operates through internal rather than external resources.

Understanding the actual psychology underneath these patterns changes how you interact with the world. Instead of trying to process faster, you can leverage the advantages of thorough analysis. Rather than suppressing emotional depth, you can recognize it as enhanced sensitivity rather than oversensitivity. Your internal preparation becomes strategic planning rather than hesitation. Your detailed memories become valuable organizational knowledge rather than overthinking.

The psychology of how your mind works reveals something essential about who you are. You’re not a broken extrovert who needs fixing. You’re operating on a different psychological architecture that produces distinct cognitive strengths. The research validates what you’ve probably known intuitively: your brain works differently, and that difference creates genuine advantages when you stop trying to force it into patterns designed for different psychological wiring.

After twenty years of working with diverse personality types, I’ve seen how understanding these psychological mechanics transforms professional effectiveness. When you recognize that your deeper processing isn’t a disadvantage but a different optimization strategy, you can build work approaches that leverage rather than fight your natural psychological patterns. The teams I’ve managed most successfully were those where I stopped apologizing for my processing style and started using it as the strategic asset it actually is.

Your psychology isn’t a problem to solve. It’s a sophisticated system to understand and apply. The cognitive architecture, emotional depth, internal workspace capacity, memory patterns, and psychological resilience that characterize how your brain works create a distinct way of engaging with the world. Research continues revealing the neurological and cognitive foundations underneath these patterns, validating what lived experience has already taught: different doesn’t mean deficient.

The question isn’t whether your psychological wiring matches someone else’s. The question is whether you’ve learned to work with the architecture you have rather than against it. Understanding the actual psychology of how your mind processes information, regulates emotion, forms memories, and builds resilience provides the foundation for that shift. Your brain works the way it does for specific cognitive reasons. Those reasons create both challenges and advantages. Recognizing which is which makes all the difference.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes the psychology of introversion different from extroversion?

The primary psychological differences involve neural pathway length, processing depth, emotional sensitivity, and internal versus external orientation. Neurological studies demonstrate that information travels through longer, more complex brain pathways for those wired for depth, engaging regions associated with planning, internal processing, and detailed analysis rather than immediate external response. These patterns create fundamentally different cognitive strategies rather than simply different social preferences.

Can psychological wiring change over time?

Core psychological architecture remains relatively stable throughout life, though behavioral adaptation and coping strategies can develop significantly. Neuroplasticity allows for some modification of processing patterns, particularly in response to sustained environmental demands or deliberate practice. That said, the underlying cognitive preferences and neural pathway characteristics tend to persist even as surface behaviors become more flexible.

How does psychology explain why some situations feel more draining than others?

Cognitive load theory explains that different activities consume mental resources at different rates. For individuals wired for internal processing, situations requiring constant external engagement, rapid-fire social interaction, or superficial rather than deep processing create higher cognitive load. The psychological energy depletion comes from operating against natural processing preferences rather than from the social interaction itself.

Does psychological sensitivity mean emotional instability?

Psychological sensitivity refers to enhanced emotional awareness and nuanced processing rather than emotional instability. Research distinguishes between emotional reactivity and emotional depth. Enhanced sensitivity to emotional information actually supports better emotional regulation through increased awareness and more sophisticated processing capabilities. The psychological pattern involves processing more emotional data rather than being overwhelmed by emotions.

How can understanding psychology improve daily functioning?

Psychological self-awareness allows for better environmental design, more effective communication strategies, and reduced internal conflict. When you understand that your slower verbal processing reflects deeper analysis rather than poor communication skills, you can build preparation time into important conversations. Recognizing detailed memory encoding helps you leverage this advantage for organizational knowledge rather than viewing it as overthinking. Understanding your psychological architecture enables strategic alignment rather than constant adaptation to incompatible patterns.

Explore more psychological insights and practical applications in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.