You know that sinking feeling when a professor announces participation will count for 30% of your grade? For quiet students, this moment transforms learning into performance anxiety.

During my years leading creative teams in advertising, I watched similar dynamics play out in conference rooms. The loudest voices dominated brainstorming sessions while the reflective thinkers sat silent, their ideas fully formed but never spoken. I learned something crucial: the best campaign concepts often came from those who spoke last, not most. When I finally asked these quieter team members to submit written proposals before meetings, the quality of our work improved dramatically.

Research from a 2023 study published in Educational Research confirms that verbal participation depends heavily on classroom organization. Traditional “initiate-response-evaluate” models favor quick verbal responses over thoughtful contribution, putting reflective learners at a systematic disadvantage.

Being quiet in class doesn’t equal disengagement. It signals a different processing style that modern education systematically undervalues. Many students discover effective strategies for classroom success once they understand their natural learning preferences.

Why Participation Grades Create Invisible Barriers

The participation grade system operates on a flawed assumption: verbal contribution equals intellectual engagement. Educational research from 2020 involving quiet college students revealed that participants exerted considerable mental effort managing their physical classroom environment to maintain focus. These students made deliberate choices about seating and movement to maximize learning, not to avoid participation.

Think about how traditional grading works. Students who speak frequently earn full credit regardless of insight quality. Those who process internally before contributing get penalized for quantity, not rewarded for depth. One student interviewed in research at the University of Oregon explained the frustration perfectly: “I watch other students who speak often and I am frustrated by the knowledge that they are being rewarded for the quantity of their participation.”

In my agency experience managing Fortune 500 accounts, I saw this pattern repeat in client presentations. Junior team members who delivered polished, thoughtful analysis received less credit than those who jumped into every discussion. Once I started evaluating contribution quality over frequency, team dynamics shifted. The quiet strategists found their voice.

This isn’t about coddling shy students. It’s about recognizing that students weigh multiple factors when deciding to participate, including classroom safety, instructor warmth, question complexity, and available thinking time. Even students who identified as “painfully quiet” could name classroom conditions where they’d feel safe contributing.

The Processing Speed Problem

Class discussions move fast. Ideas fly back and forth, topics shift, and the conversation evolves. For reflective processors, this pace creates an impossible situation.

The University of Oregon research captured this perfectly: “During a typical class discussion, I feel as though the conversation is going by at such a rapid pace that I am unable to formulate an idea quickly enough to interject it into the conversation. As I am formulating my idea and thinking it through, the topic of the discussion has changed.” This challenge becomes particularly acute during the transition to college-level coursework where discussion-based learning intensifies.

This describes a cognitive style difference, not a deficit. Reflective thinkers integrate new information with existing knowledge before speaking. They test ideas internally, consider counterarguments, and refine conclusions. This process produces higher-quality insights but requires time that fast-paced discussions don’t allow.

When professors tell these students their written work exceeds their verbal contributions, they’re not discovering hidden talent. They’re seeing what happens when processing time matches cognitive style. The student hasn’t magically become smarter in writing. They’ve had time to think.

One of my best creative directors worked exactly this way. In real-time brainstorming sessions, she contributed little. Give her 24 hours to reflect, and she’d return with the most innovative solutions. I learned to send discussion topics ahead of meetings and follow up afterwards for written input. Our campaign quality soared.

What Teachers Frequently Misunderstand About Quiet Students

A 2025 study using Q methodology identified four distinct teacher profiles regarding classroom silence. Results showed teachers recognize silence as essential for learning, but interpretations and applications vary dramatically.

Many teachers assume silence signals disinterest or lack of preparation. Research tells a different story. Students use silence strategically to gain thinking time, avoid embarrassment, and process complex information. A 2020 study on silent students found that high-achieving quiet students used silence to consolidate their position as exceptionally capable, speaking only when they had something substantial to contribute.

The problem isn’t student silence. It’s the narrow definition of participation that excludes non-verbal engagement.

Consider what research on teacher immediacy and student silence reveals: instructor warmth, body language, and gestures significantly affect student willingness to participate. Students who perceive teachers as immediate show more amenable educational practices and experience better learning outcomes. The classroom environment matters more than individual personality traits.

The Misconception of Uninvolvement

Educational researcher Smith and colleagues asserted in 2005 that “Silent students are uninvolved students who are certainly not contributing to the learning of others and may not be contributing to their own learning.” This statement represents a fundamental misunderstanding of cognitive engagement.

Quiet students aren’t uninvolved. They respond to learning environments differently. Research from 2022 published in Faculty Focus found that in reading-based competitive learning environments, those with quieter tendencies outperformed more vocal peers. Assignment type matters as much as personality type.

In my advertising career, I managed teams building campaigns worth millions. The loudest voices in planning meetings weren’t always the most valuable contributors. Some of my most brilliant strategists preferred email exchanges to conference room debates. They’d send detailed analyses that transformed our approach. Should I have graded them down for not speaking up during meetings? That would have been management malpractice.

How Classroom Design Favors Vocal Participation

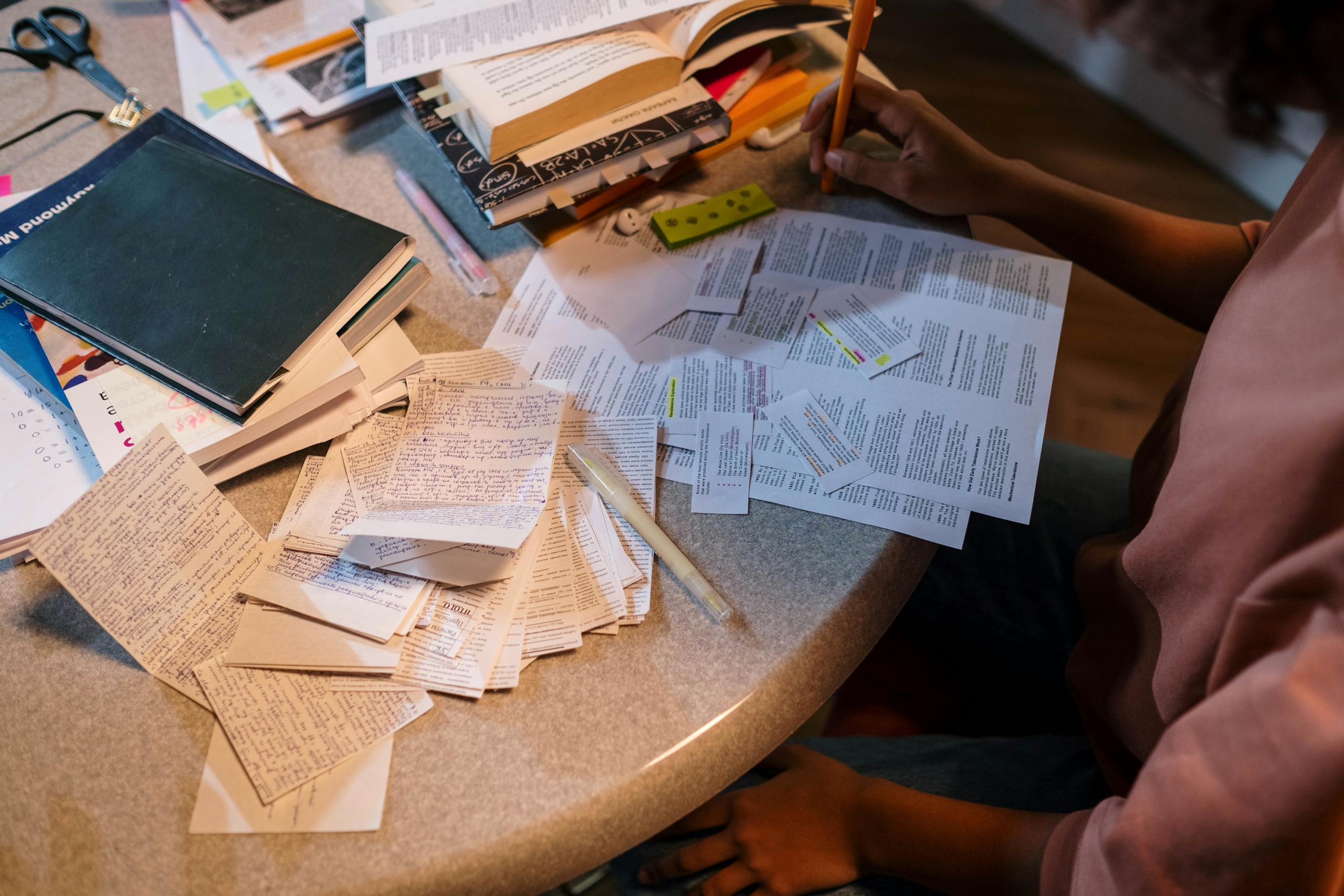

Most classrooms are engineered for extroverted learning. Constant stimulus, rapid activity changes, open discussions, and collaborative work dominate modern pedagogy. These techniques serve one learning style exceptionally well. They systematically disadvantage another.

The physical environment matters too. Quiet students make deliberate choices about classroom positioning to maintain focus and minimize unwanted interaction. Contrary to assumptions, they don’t always hide in back rows. They select seats that optimize concentration based on proximity to doors, types of seating, and distance from others.

Excessive classroom noise creates particular challenges. Students expend significant mental energy coping with environmental distractions that more stimulus-tolerant peers ignore. This cognitive load reduces available resources for actual learning. Similar dynamics play out in shared living spaces where quiet students must constantly manage sensory input.

The Group Work Dilemma

Group work has become pedagogical gospel in modern education. Collaboration mirrors professional environments, encourages peer learning, and develops communication skills. These benefits are real. So are the challenges for reflective learners.

Research on problem-based learning found that quiet tendencies didn’t exclude students from contributing to groups. Their contributions were simply non-vocal. Moments of quiet served multiple purposes: self-reflection time, space for others to contribute, and opportunities for feedback. Other students recognized and valued these contributions.

Well-designed group work includes individual reflection periods. Students choose roles matching their strengths. The structure balances discussion with contemplation. These accommodations benefit all learners, not just quiet ones. As educational systems evolve, there’s growing recognition that learning environments must adapt to serve diverse cognitive styles effectively.

Strategies That Actually Work

Effective teaching for quiet students doesn’t mean eliminating discussion or verbal participation. It means expanding what counts as meaningful contribution.

Providing Questions in Advance

Sending discussion questions beforehand transforms participation dynamics. Reflective processors get time to formulate responses, test ideas, and prepare contributions. This simple adjustment levels the playing field without disadvantaging anyone.

One professor I know emails discussion topics 48 hours before class. Students can submit written thoughts or simply prepare mentally. Classroom conversation quality improved dramatically. Quiet students contributed more frequently and substantively. Vocal students benefited from competing with more thoughtful responses.

Think-Pair-Share Structure

This technique provides reflection time within the class period itself. Students first write individual responses. They pair up to discuss. Finally, pairs share with the larger group.

The structure accommodates different processing speeds. Written reflection gives quiet students time to organize thoughts. Pair discussions feel less intimidating than whole-class participation. Sharing happens through a partner, reducing individual performance pressure.

Digital Participation Options

Online discussion boards, document comments, and digital response systems create participation channels that don’t require real-time verbal performance. Students contribute asynchronously, giving themselves time to think and refine ideas.

These aren’t shortcuts or accommodations. They’re legitimate forms of intellectual engagement that produce higher-quality contributions from reflective thinkers.

Redefining Participation Metrics

The most important shift involves how instructors measure engagement. Participation shouldn’t mean “times you spoke in class.” It should include:

Written responses that demonstrate critical thinking. Thoughtful questions asked via email or office hours. Quality of occasional verbal contributions over quantity. Evidence of engagement with assignments that synthesize class discussions. Non-verbal participation including active listening, note-taking, and reflective observation.

During client presentations, I evaluated team members on insight quality, not speaking frequency. Some people contributed breakthrough thinking in pre-meeting emails. Others asked the one question that reframed our entire approach. Both deserved equal credit for participation.

What Quiet Students Can Do Now

Waiting for education systems to change isn’t a strategy. You need tools that work in current classroom environments.

Communicate Your Learning Style

Talk to professors during office hours about your processing style. Explain that you contribute better with thinking time. Many instructors will accommodate if they understand the request.

This isn’t asking for special treatment. You’re helping teachers understand how to get your best work. Most educators want all students to succeed. They need information about what helps different learners thrive.

Use Written Channels Strategically

Email professors thoughtful questions or observations about course material. Submit optional reflection papers. Contribute substantively to online discussion boards. These actions demonstrate engagement using channels that match your processing style.

One student I advised sent weekly synthesis emails to her professor, connecting class discussions to assigned readings. The instructor incorporated her insights into subsequent lectures and gave full participation credit. Her written contributions enriched everyone’s learning. This approach proves especially effective for adult learners returning to education who bring professional experience to academic environments.

Prepare Strategic Contributions

You don’t need to speak frequently. Plan one or two substantial contributions per class session. Quality beats quantity every time.

Review discussion questions beforehand if available. Prepare a thoughtful observation or question. You’ll feel more confident speaking when you’ve had time to think. Your contribution will carry more weight than multiple off-the-cuff comments.

Find Your Classroom Position

Choose seats that optimize your concentration. This might mean sitting near the front to minimize distractions, or near the door if you need occasional breaks. Position matters for managing energy and maintaining focus.

Experiment with different locations until you find what works. Your goal is maximizing learning, not hiding. These same spatial awareness skills prove valuable beyond traditional classrooms, helping students handle unfamiliar educational environments with confidence.

Build Confidence Gradually

Start with smaller risks. Ask questions in small group settings before attempting whole-class participation. Contribute to pair discussions. Gradually expand your comfort zone.

This isn’t about becoming someone else. It’s about finding ways to share your thinking that feel authentic. Your goal isn’t matching extroverted behavior. It’s finding your own path to meaningful contribution.

The Bigger Picture: Rethinking Educational Success

Participation-focused classrooms reveal assumptions about intelligence, engagement, and success that deserve examination. Quick verbal response shouldn’t define intellectual capability. Vocal frequency isn’t synonymous with deep understanding.

The strongest teams I built in advertising included both vocal brainstormers and quiet strategists. The loudest person in the room never determined our best work. That came from combining different thinking styles, respecting varied processing speeds, and creating space for multiple forms of contribution.

Education should mirror this reality. Classrooms need verbal discussion. They also need reflection time, written exchange, and recognition that silence can signal deep thinking rather than disengagement.

Quiet students aren’t failing to participate correctly. The system is failing to recognize legitimate forms of intellectual engagement. The solution isn’t teaching quiet students to act more extroverted. It’s expanding educational definitions of what meaningful participation looks like.

Your quiet nature in the classroom might actually be your greatest academic strength. The ability to reflect deeply, process thoroughly, and contribute thoughtfully creates lasting value that quick responses rarely match. Find professors who recognize this. Communicate your needs clearly. Use channels that work with your processing style.

Success in participation-focused classrooms doesn’t require personality transformation. It requires strategic adaptation, clear communication, and confidence that thoughtful silence sometimes precedes the most valuable contributions.

Explore more quiet student resources in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is someone who embraced his true nature later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate each personality types about the power of understanding how different cognitive styles can reveal new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I improve my participation grade without forcing myself to speak more?

Talk to your professor about alternative participation methods. Offer to submit written reflections, contribute to online discussions, or ask thoughtful questions via email. Many instructors will count these as participation once they understand your processing style. Focus on quality over quantity in verbal contributions, preparing one substantial comment per class instead of multiple casual remarks.

Is being quiet in class actually holding me back academically?

Not necessarily. Research shows quiet students typically excel in areas requiring deep thinking, written analysis, and careful problem-solving. The issue isn’t your quietness but how participation gets measured. If your written work and exam performance demonstrate recognizing, you’re learning effectively. The challenge lies in showing professors that non-verbal engagement counts as participation.

What should I do when professors call on me unexpectedly?

It’s acceptable to ask for a moment to think. Try responses like “Let me consider that for a second” or “Can I come back to that after hearing a few other perspectives?” Professors who understand learning differences will respect this request. You can also prepare general responses to common question types, giving yourself frameworks to work from when caught off guard.

How can I handle group projects when everyone else dominates the conversation?

Volunteer for roles that play to your strengths like researcher, writer, or editor. Contribute substantive work outside group meetings by way of shared documents or detailed emails. Schedule separate meetings with individual group members for deeper conversations. Most importantly, recognize that your careful analysis and thorough preparation regularly exceed the value of dominating discussions.

Should I tell professors I’m introverted to explain my quiet nature?

Frame it as explaining your learning style instead of labeling yourself. Describe how you process information and contribute best. Say you value thinking time before responding, prefer written channels for complex ideas, or need questions in advance to prepare thoughtful responses. This focuses on productive strategies instead of fixed personality traits.