Your body holds stories your mind has forgotten. The tightness in your chest during meetings, the way your shoulders climb toward your ears when someone raises their voice, the churning in your stomach before social events. For years, I dismissed these signals as random physical reactions, something to power through with enough willpower.

Working in advertising meant constant pressure to perform extroverted behaviors even when my nervous system was screaming for quiet. I remember sitting in pitch presentations, my jaw clenched so tight I’d develop headaches that lasted for days. The tension would spread down my neck, across my shoulders, settling into my back. No amount of cognitive reframing or positive self-talk could touch it.

That disconnect between mind and body became my normal. I could intellectually understand stress management strategies while my body remained locked in a defensive state. The breakthrough came when I discovered somatic therapy and learned that my physical symptoms weren’t separate from my mental health, they were central to it.

What Somatic Therapy Actually Is

Somatic therapy works with the premise that traumatic experiences and chronic stress create changes in how your nervous system functions. Unlike traditional talk therapy that focuses primarily on thoughts and memories, somatic approaches direct attention to internal physical sensations, what you feel in your muscles, organs, and tissues.

The approach emerged from the work of Peter Levine, who developed Somatic Experiencing in the 1970s. His theory centers on how animals in the wild naturally discharge stress after threatening encounters, while humans often suppress these instinctive responses. That suppression becomes stored tension, anxiety, and physical symptoms that persist long after the initial threat has passed.

Research demonstrates significant effectiveness for somatic therapy in treating PTSD, with one randomized controlled trial showing strong intervention effects for both trauma symptoms and depression. What makes this particularly relevant for introverts is the method’s emphasis on gradual, internal processing rather than intense emotional exposure.

The therapy involves three primary types of bodily awareness. Interoception means sensing internal body states, hunger, heartbeat, muscle tension. Proprioception involves understanding where your body exists in space. Kinesthetic awareness tracks how your body moves. During my agency years, I had virtually no connection to any of these. I existed almost entirely in my head, analyzing, planning, strategizing.

Why Introverts Benefit From Body-Based Approaches

Introverts process information deeply, filtering experiences through layers of internal reflection. This strength becomes a vulnerability when dealing with trauma or chronic stress. We can get caught in loops of cognitive analysis, trying to think our way out of states that exist below conscious awareness in our nervous systems.

Managing creative teams taught me that some behaviors that appear like introversion are actually trauma responses. The constant need for control, hypervigilance about others’ moods, difficulty trusting colleagues, these weren’t personality traits but nervous system adaptations to past experiences.

Somatic therapy offers a pathway that honors introverted processing styles. Instead of requiring extensive verbal articulation of traumatic memories, it guides attention to present-moment physical sensations. This allows for healing without forcing the kind of rapid-fire emotional disclosure that can feel overwhelming for introverts.

Your natural inclination toward self-reflection becomes an asset in somatic work. The therapy requires patient observation of subtle internal shifts, exactly the kind of detailed awareness introverts excel at developing. When a therapist asks what you notice in your body right now, your capacity for nuanced self-observation provides rich material for the work.

The controlled pace suits introverted nervous systems particularly well. Somatic practices emphasize present moment awareness and mindfulness, gradually building tolerance for physical sensations rather than pushing through discomfort. This respects the introverted need for processing time and internal integration.

Understanding the Nervous System Response

Polyvagal theory explains how feelings of safety emerge from inside the body, not from external circumstances. The vagus nerve, which runs from your brainstem through most of your organs, plays a central role in how you experience safety, connection, and threat.

When your nervous system detects danger, real or perceived, it responds through three hierarchical states. Social engagement allows connection and calm. Mobilization activates fight or flight responses. Immobilization triggers shutdown and dissociation. During my most intense agency periods, I lived almost exclusively in mobilization, my body primed for threat even during routine tasks.

Chronic stress retunes your autonomic nervous system to remain locked in defensive states. Your body continues responding to neutral situations as if they’re dangerous. Someone asking a simple question in a meeting triggers the same physical cascade as an actual threat. The rational mind knows there’s no danger, but the body hasn’t gotten that message.

For introverts, this gets complicated by social expectations that conflict with our nervous system needs. We need quiet, solo time to regulate and restore. Our culture often interprets this as antisocial or problematic, adding shame on top of the existing dysregulation. You learn to push through your body’s signals, creating deeper disconnection.

Somatic therapy helps rebuild the connection between your conscious awareness and your autonomic state. Instead of overriding your body’s messages, you learn to listen to them. This doesn’t mean indulging every impulse for avoidance, but rather understanding what your nervous system is communicating about safety and threat.

Core Techniques and How They Work

Resource development forms the foundation. Before approaching difficult material, you identify what helps you feel safe and grounded. This might be imagining a peaceful place, remembering a supportive relationship, or focusing on a part of your body that feels comfortable. Having established resources allows your nervous system to know it has anchors when working with challenging sensations.

Pendulation means oscillating between activation and calm. A therapist might guide you to notice tension in your shoulders, then shift attention to your feet on the ground. Back to the tension, then to your breathing. This gentle rhythm trains your nervous system to move between states rather than getting stuck in either extreme.

When leading strategy meetings, I’d practice this without realizing it was a technique. If anxiety started building, I’d focus on the texture of my notebook, the stability of my chair, the rhythm of my breath. Small anchors that brought me back from spiraling thoughts into present physical reality.

Titration involves approaching difficult sensations gradually, in manageable doses. Rather than flooding you with overwhelming emotion, somatic approaches carefully meter exposure to distressing material. This prevents retraumatization and builds confidence in your capacity to handle what arises.

Tracking sensations means developing precise awareness of what happens in your body moment to moment. A therapist might ask: Where do you feel that in your body? How big is that sensation? Does it have a temperature? A texture? This detailed attention reveals patterns and helps discharge stuck energy.

Completion of defensive responses allows your body to finish protective actions that got interrupted. If you froze during a threatening situation, somatic work might guide you to slowly push away with your arms, giving your system the experience of successful defense. The body processes this completion at a neural level.

Practical Application for Introverted Lives

Body scans provide a accessible entry point. Lie down in a quiet space and systematically bring attention to each part of your body, from toes to head. Notice any sensations without trying to change them. Tension, warmth, tingling, numbness, just observe. This builds the interoceptive awareness that underlies somatic work.

Grounding techniques help when you feel overwhelmed or dissociated. Five-point grounding involves naming five things you can see, four you can hear, three you can touch, two you can smell, and one you can taste. This anchors you in present sensory reality rather than past memories or future worries.

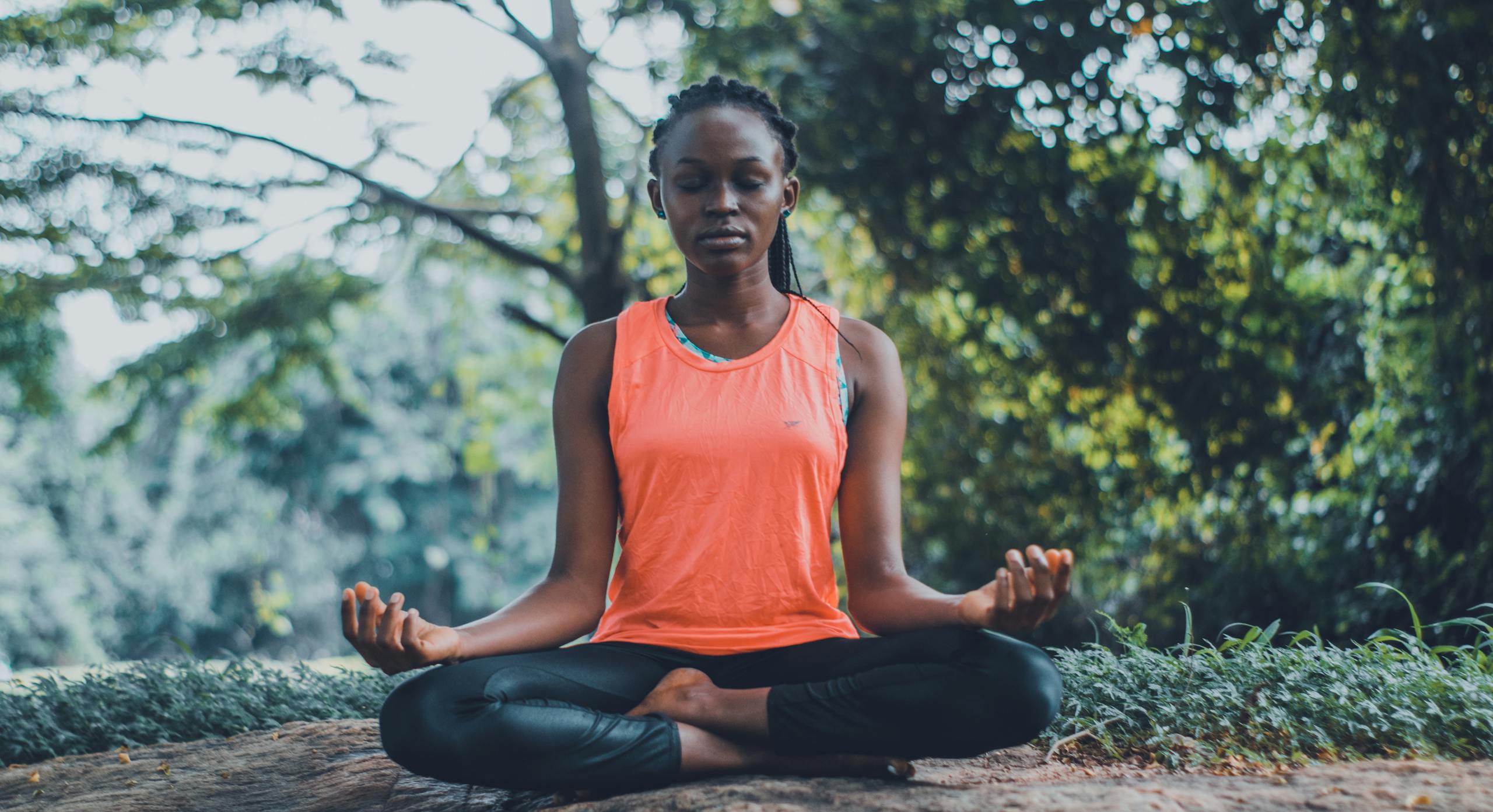

Gentle movement practices like tai chi, qigong, or slow yoga complement somatic therapy beautifully. These disciplines share the emphasis on internal awareness and mindful attention to sensation. They provide structured ways to develop body awareness outside therapy sessions.

Breath awareness serves as a portable regulation tool. Place one hand on your chest, one on your belly. Notice which moves more as you breathe. Gradually shift to deeper belly breathing, letting your diaphragm do more work. This activates your vagus nerve and signals safety to your nervous system.

Building a comprehensive mental health approach means integrating somatic awareness with other strategies. Track your physical state alongside your thoughts and emotions. Notice patterns, do you hold tension in specific areas during certain situations? Does your breathing change when particular people are present?

Combining Somatic Work With Other Therapies

Somatic approaches complement rather than replace other therapeutic methods. Understanding trauma from a polyvagal perspective enhances cognitive behavioral work by addressing the physiological foundation beneath thought patterns.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can benefit from somatic integration. When challenging anxious thoughts, notice what happens in your body as the thought shifts. The cognitive change becomes embodied, creating deeper transformation than intellectual understanding alone provides.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) and somatic therapy work exceptionally well together. IFS identifies different parts of your psyche, the critic, the protector, the wounded child. Somatic awareness helps locate where each part lives in your body. The critic might sit in your clenched jaw, the protector in your tense shoulders, the wounded part in your tight chest.

During complex restructures at my agency, I’d notice how different parts of me held tension differently. The leader part created rigidity in my spine, upright, controlled, alert. The uncertain part manifested as a knot in my solar plexus. Acknowledging both physical signatures helped me respond more skillfully to challenging situations.

Mindfulness-based approaches and somatic therapy share considerable overlap. Both emphasize present-moment awareness and non-judgmental observation. The combination strengthens your capacity to stay present with difficult sensations rather than immediately trying to escape or fix them.

Common Challenges and How to Work Through Them

Initial body awareness can feel overwhelming. After years of living in your head, suddenly tuning into physical sensations might reveal more discomfort than you anticipated. Start small. Five minutes of body scan practice is sufficient. Gradually build tolerance for internal awareness.

Numbness or disconnection from your body is common, especially with long-term trauma. This doesn’t mean somatic therapy won’t work, it means you need gentler, more gradual approaches. Your therapist might start with noticing temperature, texture of clothing, or pressure of your body against the chair before moving to internal sensations.

Hyperawareness creates the opposite problem. Some introverts develop such acute body awareness that every sensation becomes concerning. The key is cultivating curiosity rather than alarm. When you notice tension, ask what it’s communicating rather than immediately trying to eliminate it.

Finding qualified practitioners requires research. Look for therapists specifically trained in Somatic Experiencing, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, or similar body-based modalities. Ask about their training, years of experience with somatic work, and how they integrate it with other approaches.

Cost and accessibility present real barriers. While specialized somatic therapy can be expensive, many techniques can be learned through books, online courses, or group classes. Basic interoceptive awareness practices don’t require a therapist, though professional guidance helps with deeper trauma work.

Integration Into Daily Life

Morning body checks establish a baseline. Before getting out of bed, spend two minutes scanning your body. How does your nervous system feel this morning? Calm? Activated? Shut down? This information helps you adjust your day’s expectations and self-care accordingly.

Micro-practices throughout the day maintain connection. When waiting for coffee to brew, notice your feet on the ground. During work breaks, do quick shoulder rolls while tracking the sensations. Walking from your car to the office, feel your muscles working, your lungs expanding, your feet contacting the earth.

As an agency executive, I had to find ways to stay regulated during intense periods. Between client calls, I’d close my office door for 60 seconds of conscious breathing. During presentations, I’d ground through my feet while speaking. Small practices that kept me connected to my body even in demanding circumstances.

Evening wind-down routines support nervous system regulation. Gentle stretching, progressive muscle relaxation, or restorative yoga poses signal to your body that the day’s activation phase is ending. This helps prevent carrying tension into sleep.

Social situations become more manageable with somatic awareness. Notice when your nervous system starts feeling overwhelmed, tension building, breathing shallowing, dissociation beginning. These are cues to excuse yourself, find quiet space, and use grounding techniques before pushing through to complete exhaustion.

Measuring Progress and Setting Realistic Expectations

Somatic healing follows a different timeline than cognitive therapy. Research on somatic experiencing shows preliminary evidence of positive effects, but individual progress varies considerably. Some people notice shifts within weeks, others need months of consistent practice.

Track changes in physical symptoms rather than just emotional states. Are your chronic headaches less frequent? Is your jaw less clenched? Does your stomach feel calmer? These bodily shifts often precede noticeable changes in mood or thought patterns.

Increased capacity for sensation indicates progress. As your nervous system becomes more regulated, you can tolerate bigger emotional experiences without shutting down or flooding. You might notice you can stay present during difficult conversations, cry when sad without spiraling, or feel anger without explosive reactivity.

Setbacks are part of the process, not failures. Stress, illness, or life changes can temporarily reduce your capacity for regulation. The difference is that with somatic skills, you recognize what’s happening and have tools to work with it rather than feeling helplessly swept away.

During my transition from agency life, my regulation capacity fluctuated dramatically. Some weeks I felt solid, grounded, capable. Others, old patterns of tension and disconnection returned. Gradually, the regulated periods lasted longer and the dysregulated ones became less intense and shorter.

Creating a Supportive Environment

Physical space affects nervous system regulation. Your home environment either supports or undermines somatic healing. Consider lighting, harsh fluorescents trigger stress responses while softer natural light promotes calm. Sound matters too, constant background noise increases activation even when you’re not consciously aware of it.

Temperature regulation helps maintain physical comfort necessary for body awareness. Cold activates your sympathetic nervous system, warmth promotes parasympathetic calm. Having blankets, comfortable seating, and temperature control supports the vulnerable state of tuning into your body.

Minimize unnecessary stimulation during practice time. Turn off devices, reduce visual clutter, create predictable routines. Your nervous system can relax more fully when it doesn’t need to process constant novelty and potential threats.

Communicate boundaries with people in your life. Explain that you’re doing work that requires quiet time for body awareness. Most people understand when you say you need 15 minutes of uninterrupted space for a grounding practice.

Build in recovery time after difficult somatic work. Processing stored trauma or intense emotions through your body takes energy. Don’t schedule demanding activities immediately after therapy sessions or deep practice. Give yourself space to integrate what’s emerged.

Your body has been trying to tell you things for a long time. The tension, the fatigue, the digestive issues, the shallow breathing, these aren’t obstacles to overcome through willpower. They’re communications from your nervous system about what it needs to feel safe.

Somatic therapy provides a language for this conversation. Instead of dismissing physical symptoms or trying to think them away, you learn to listen, respond, and gradually restore regulation. For introverts who already possess deep self-awareness, this becomes a natural extension of your introspective strengths.

The work isn’t always comfortable. Reconnecting with your body after years of disconnection means feeling things you’ve been avoiding. But this discomfort differs fundamentally from the chronic dysregulation of an untended nervous system. One leads toward healing, the other perpetuates suffering.

You deserve to feel at home in your body, to trust its signals, to experience the full range of physical sensations without fear or shutdown. Somatic therapy offers a pathway there, not through forced extroversion or overriding your nature, but through deeper connection with the wisdom your body has been holding all along.

Explore more mental health resources in our complete Introvert Mental Health Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.