Everyone celebrates the quiet power of introversion these days. Books fly off shelves proclaiming our thoughtful nature. Articles praise our listening skills and depth of character. Yet beneath this celebration lies something we rarely discuss openly: introversion carries genuine challenges that can derail your wellbeing if left unaddressed.

During my twenty years running advertising agencies, I became an expert at hiding these struggles. Clients expected confident leadership. My teams needed decisive direction. So I performed extroversion like an actor who never breaks character, even as it slowly consumed my energy reserves. Only after leaving corporate life did I confront what that performance had cost me.

This article examines the shadow side of introversion that wellmeaning advocates often gloss over. Not to discourage you from embracing your nature, but to arm you with awareness. Because understanding these challenges is the first step toward managing them effectively.

The Loneliness Paradox That Catches Us Off Guard

Here is something that confused me for years: I craved solitude yet felt achingly lonely. How could both things be true simultaneously? A 2023 study published in BMC Psychology helped me understand this paradox. Researchers found that introversion correlates with higher levels of loneliness, even though introverts actively seek time alone.

The distinction matters more than most people realize. Solitude represents a choice. Loneliness represents a deficit. You can choose solitude and still feel disconnected from meaningful relationships. Many introverts maintain smaller social circles, which works beautifully when those relationships provide depth and support. Problems emerge when we mistake quantity for quality or when our preference for solitude gradually erodes the connections we do have.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that approximately one in three adults experience loneliness, and the health consequences prove startling. Social isolation increases risk for heart disease, stroke, depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. These effects compound over time, creating cycles that become increasingly difficult to break.

I remember attending industry conferences and feeling surrounded by hundreds of people yet entirely alone. The superficial networking drained me without filling my actual need for connection. Afterward, I would return to my hotel room exhausted, wondering why all that socializing left me feeling emptier than before. The answer, I eventually realized, involved quality over quantity. Brief conference conversations provided stimulation without intimacy, leaving my real social needs unmet.

What makes this particularly challenging for introverts is that addressing loneliness requires the very activities that deplete us. Building deeper relationships demands time, energy, and vulnerability. For someone whose social battery drains quickly, investing that energy strategically becomes essential. Random social activities drain without replenishing. Targeted connection with the right people fills the well.

When Deep Thinking Becomes Destructive Rumination

Our capacity for deep reflection represents one of introversion’s greatest gifts. We examine ideas from multiple angles. We consider implications others miss. We process experiences thoroughly before responding. Yet this same capacity can turn against us when reflection transforms into rumination.

Research published in World Psychiatry describes rumination as repetitive negative thinking that circles without resolution. Unlike productive reflection, which moves toward insight and action, rumination traps us in loops of worry, regret, and self criticism. The same neural pathways that enable our thoughtfulness can create grooves that pull us toward negativity.

Scientists have identified that the frontal cortex and Broca’s area, both highly active in introverts, play central roles in this process. We process more information per second than extroverts on average, which helps explain why introverts often overthink. Our brains simply run more background processes, leaving more opportunities for thoughts to spiral in unproductive directions.

After difficult client meetings, I would replay conversations for days. What did that comment really mean? Should I have responded differently? Did I come across as confident enough? These questions would loop endlessly, stealing sleep and generating anxiety about future interactions. The irony was painful: my tendency toward preparation and reflection, which made me effective in my role, became the same tendency that kept me awake at 3 AM second guessing every word.

A key distinction separates introspection from rumination, as noted in Psychology Today. Productive introspection leads somewhere. It generates insight, resolves questions, and moves you forward. Rumination circles the same territory repeatedly without resolution. It amplifies negative emotions rather than processing them. Recognizing which mode you occupy at any moment represents the first step toward redirecting your mental energy.

Breaking rumination cycles requires deliberate intervention. Mindfulness practices help by anchoring attention to the present moment rather than past regrets or future worries. Physical activity serves as another effective pattern interrupt, shifting your brain out of circular thinking. For particularly stubborn loops, scheduling specific worry time can contain the rumination rather than allowing it to bleed across your entire day.

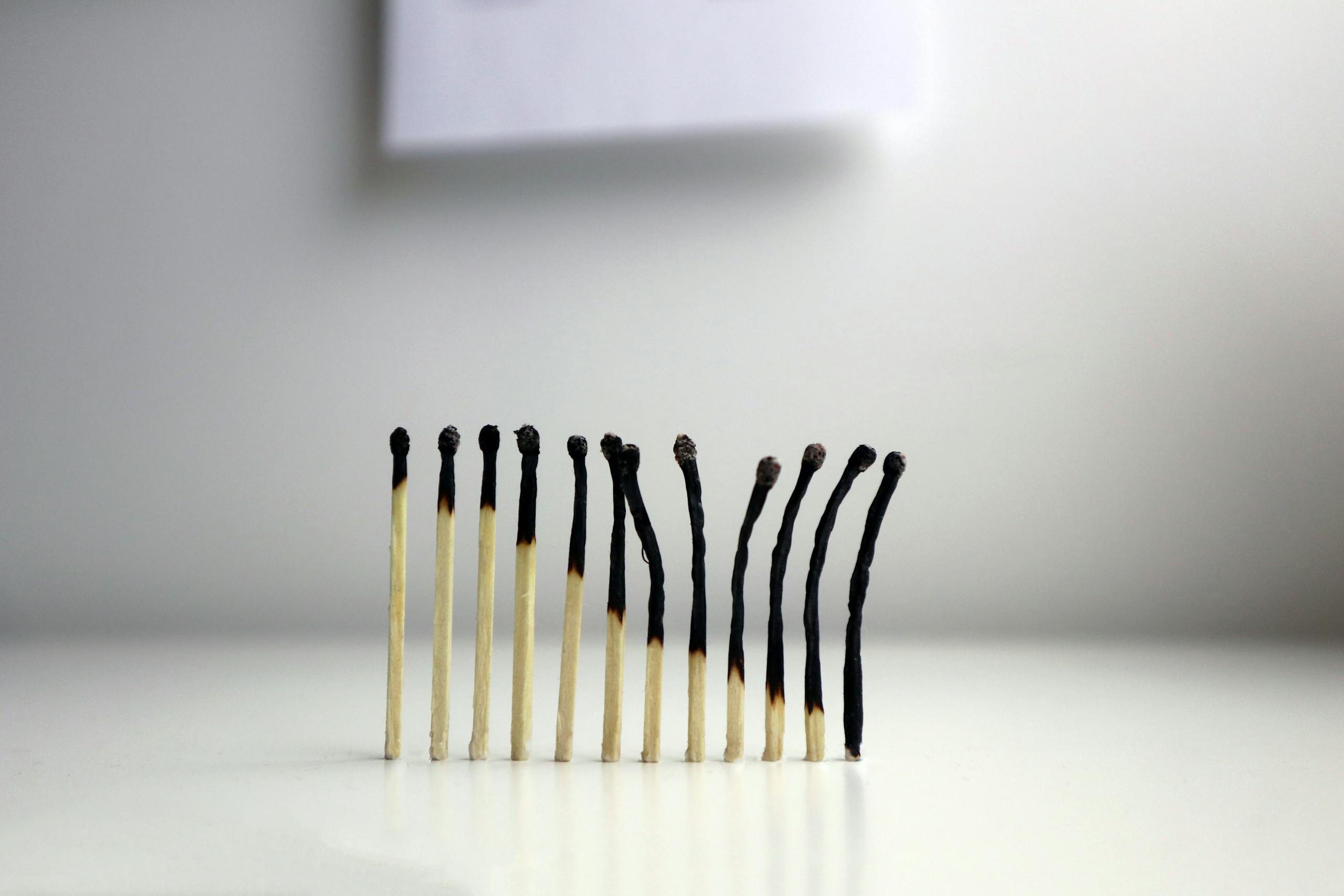

The Hidden Cost of Wearing Social Masks

Every introvert I know has developed a performance persona for professional and social situations. We smile bigger, project louder, and engage more energetically than feels natural. This adaptation serves practical purposes. It helps us succeed in environments that reward extroverted behavior. It prevents misunderstandings about our intentions or capabilities.

What we discuss less frequently is the toll this performance exacts. Psych Central describes social exhaustion as an emotional and physical response to overstimulation that leaves you feeling drained and depleted. For introverts wearing social masks, this exhaustion compounds because we expend energy not just on interaction but on maintaining a persona that differs from our authentic selves.

Throughout my agency years, I maintained what I privately called my CEO character. This version of me made quick decisions publicly (then agonized over them privately). This version appeared energized by back to back meetings (then collapsed in silence at home). This version networked effortlessly at industry events (then avoided similar gatherings in my personal life for weeks afterward).

The cognitive load of this performance accumulated over time. By midweek, I would feel depleted regardless of how much sleep I got. By Friday, simple conversations felt like climbing mountains. Weekends became recovery periods rather than enjoyment periods. I was living for the spaces between obligations rather than finding fulfillment within my actual life.

Many introverts feel pressured to act extroverted in workplaces and social settings that reward outgoing behavior. We learn early that speaking up gets rewarded, that networking opens doors, that visibility matters for advancement. These lessons are not wrong, exactly, but they create pressure to suppress our natural tendencies. Over time, that suppression becomes exhausting.

The research on this phenomenon reveals troubling patterns. People who pretend to be extroverted experience delayed exhaustion that hits hours after social events. They guard their solitude fiercely because recovery time has become precious and scarce. They often maintain amplified personas that require conscious effort to sustain, leaving them feeling inauthentic even during successful interactions.

Mental Health Vulnerabilities We Rarely Acknowledge

Evidence suggests that introverts face elevated risks for certain mental health challenges. A Harvard Health study found that both loneliness and social isolation correlate with poor health outcomes, but their effects differ. Social isolation predicts physical decline and earlier mortality, while loneliness proves more predictive of mental health issues like depression.

This matters for introverts because our lifestyle choices can inadvertently increase both isolation and loneliness. Preferring quiet evenings at home is entirely healthy. Avoiding all social contact because interaction feels exhausting crosses into territory that may harm our wellbeing over time. The line between preference and avoidance can blur gradually enough that we fail to notice when we have crossed it.

I experienced this blur firsthand during a particularly demanding stretch of work. Evenings alone with a book felt like necessary recovery. Then evenings became weekends. Then weekends stretched into weeks where I saw no one outside work obligations. My preference for solitude had morphed into isolation without my conscious awareness. By the time I recognized the pattern, I had drifted far from the relationships I valued.

The connection between introversion and depression deserves particular attention. Research consistently shows that introverts demonstrate higher vulnerability to depressive symptoms than their extroverted counterparts. This does not mean introversion causes depression, but rather that certain aspects of introversion, such as rumination tendencies and smaller support networks, may increase susceptibility.

Understanding these vulnerabilities does not mean accepting them as inevitable. Nature Mental Health emphasizes that healthy social relationships provide protective benefits comparable to other major health interventions. For introverts, this means cultivating connections strategically rather than abandoning social engagement entirely. Quality relationships with a few trusted people may matter more than extensive social networks.

The Self Sabotage Patterns Worth Examining

Our introversion can become a convenient excuse for avoiding challenges that would benefit us. Speaking up in meetings feels uncomfortable, so we stay silent and miss opportunities to contribute. Networking events drain us, so we skip them and watch colleagues advance past us. Confrontations deplete our energy, so we avoid necessary conversations and let problems fester.

These patterns often emerge from legitimate introvert needs. We genuinely do require energy management. We authentically do process information differently than extroverts. We validly do need recovery time after social exertion. The challenge lies in distinguishing between honoring our nature and hiding behind it.

During my corporate career, I watched brilliant introverts sabotage their own advancement by refusing to engage with workplace politics. They dismissed networking as shallow. They resented self promotion as unseemly. They expected their work to speak for itself while watching less talented but more visible colleagues get promoted. Their principled stance was understandable. It was also counterproductive.

I made similar mistakes. I convinced myself that avoiding certain situations preserved my energy for more important work. In reality, those avoided situations often held precisely the opportunities I needed. The discomfort I dodged in the short term created larger problems in the long term. My introversion provided perfect cover for fear disguised as preference.

Examining our patterns honestly requires distinguishing between genuine energy management and avoidance. Declining a third social event in one week because you need recovery time honors your nature. Declining all social events because they might be uncomfortable uses introversion as armor against growth. Both look similar from the outside, but the internal motivations differ significantly.

The experience of imposter syndrome hits introverts with particular force. Our tendency toward self reflection can amplify self doubt. Our awareness of what we do not know can overshadow confidence in what we do know. Combined with workplace cultures that often reward extroverted expression, many introverts internalize messages that something is fundamentally wrong with how they operate.

The Discrimination That Still Persists

Despite increased awareness of introversion, bias against quiet people remains embedded in many professional and social environments. Open office plans disadvantage those who need quiet concentration. Meeting cultures reward those who think out loud rather than those who think before speaking. Performance evaluations often emphasize collaboration and communication in ways that penalize introverted work styles.

This bias represents one of the last acceptable prejudices in professional settings. Calling someone too quiet or saying they need to come out of their shell would draw criticism if directed at other personal characteristics. Yet introverts hear these comments regularly, often framed as helpful feedback rather than the bias they represent.

I encountered this bias constantly in advertising, an industry that fetishizes charisma and presentation. Client pitches rewarded dramatic delivery over sound strategy. Internal meetings favored quick responses over considered ones. Colleagues who held court at happy hours built relationships that translated into career advancement, while those who preferred one on one conversations were labeled standoffish.

These environmental pressures compound the internal challenges introverts already face. Managing our energy becomes harder when workplaces demand constant availability. Authentic expression becomes riskier when cultures reward extroverted performance. Building supportive relationships becomes more difficult when networking norms favor large group interactions over the intimate conversations where we thrive.

Understanding that these barriers exist externally helps separate structural challenges from personal limitations. Some of what feels like individual failure actually reflects environmental mismatch. Recognizing the difference allows for more targeted responses: adapting where necessary, advocating for change where possible, and preserving energy for the battles that matter most.

Moving From Awareness to Action

Acknowledging these shadow aspects of introversion does not mean accepting them as permanent or insurmountable. Awareness creates opportunity. Once you recognize patterns, you can intervene intentionally rather than being controlled unconsciously.

Start by examining your relationship with solitude honestly. Does your time alone feel restorative or isolating? Do you emerge from quiet periods refreshed or more withdrawn? The answers reveal whether your solitude habits serve your wellbeing or have drifted into avoidance.

Monitor your thinking patterns with similar honesty. Reflection that produces insight differs fundamentally from rumination that produces anxiety. When you notice your thoughts circling without resolution, that awareness signals time for intervention. Physical activity, mindfulness techniques, or simply changing your environment can break the cycle.

Consider the cost of your social masks. Some performance proves necessary for professional success. Complete authenticity is neither possible nor desirable in all situations. Yet chronic masking extracts a toll. Finding environments where you can be more fully yourself reduces the overall energy drain and creates space for genuine connection.

Build relationships strategically rather than extensively. A few deep connections provide more support than many superficial ones. Invest your limited social energy in relationships that offer mutual understanding and genuine care. Accept that maintaining a smaller circle is not a failure but a feature of your approach to connection.

Distinguish between preference and avoidance in your choices. Declining social invitations to protect your energy is healthy. Declining all growth opportunities because they involve discomfort limits your potential. The path forward lies in strategic engagement rather than blanket avoidance or exhausting overextension.

Embracing the Full Picture

These challenges do not diminish the genuine strengths of introversion. Our capacity for deep thought, meaningful connection, creative insight, and sustained concentration remain valuable gifts. Acknowledging the shadow aspects does not erase the light.

What honesty provides is completeness. Celebrating introversion while ignoring its challenges leaves us unprepared for difficulties we will inevitably encounter. Understanding both sides equips us to maximize our strengths while managing our vulnerabilities.

My years of pretending to be someone I was not cost me significantly. Burnout, disconnection, and chronic exhaustion were the prices I paid for performing extroversion I did not possess. Only by confronting these patterns honestly could I begin building a life that actually fits how I am wired.

You deserve that same honest reckoning. Not to discourage embracing your introversion, but to embrace it completely, shadow and light together. Because wholeness requires seeing clearly, and seeing clearly enables choices that serve who you actually are.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do introverts struggle with loneliness when they prefer solitude?

Solitude and loneliness represent different experiences. Solitude is a chosen state of being alone that feels restorative. Loneliness is an unwanted feeling of disconnection regardless of how many people surround you. Introverts need solitude for energy recovery but still require meaningful relationships for emotional fulfillment. Problems arise when preference for solitude inadvertently reduces opportunities for the deep connections that prevent loneliness.

How can introverts tell if their reflection has become unhealthy rumination?

Healthy reflection moves toward resolution and insight. Rumination circles the same thoughts repeatedly without progress. If your thinking produces understanding, changed perspective, or action plans, it serves you well. If the same worries or regrets replay endlessly while your mood deteriorates, you have crossed into rumination. Time awareness helps: productive reflection typically resolves within hours, while rumination can persist for days or weeks on the same topic.

What are the warning signs of introvert burnout?

Physical exhaustion that sleep does not resolve, irritability that feels disproportionate to situations, difficulty concentrating on simple tasks, and emotional numbness or flatness all signal potential burnout. Many introverts also experience withdrawal from activities they normally enjoy, increased need for isolation beyond usual preferences, and physical symptoms like headaches or digestive issues. These signs often develop gradually, making them easy to dismiss until burnout becomes severe.

Can introversion actually cause depression?

Introversion itself does not cause depression, but certain aspects of introversion may increase vulnerability. Tendencies toward rumination, smaller social support networks, and sensitivity to overstimulation can create conditions where depression becomes more likely. Environmental factors like workplace bias against quiet people add additional pressure. Understanding these vulnerabilities enables proactive management rather than passive acceptance of increased risk.

How can introverts build meaningful relationships without exhaustion?

Focus on depth over breadth. A few genuine connections provide more support than many superficial ones and require less energy to maintain. Choose relationship activities that align with your strengths, such as one on one conversations, shared activities that do not require constant talking, or written communication. Schedule social time strategically, ensuring recovery periods between engagements. Accept that your approach to friendship differs from extroverted norms without being inferior to them.

Explore more resources on introvert life in our complete General Introvert Life Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.