My assistant walked into my office one Tuesday afternoon, concern written across her face. “Everyone’s wondering if you’re okay,” she said quietly. “You’ve been in here with the door closed for three days.” What she didn’t know was that those three days behind a closed door were keeping me functional. After leading a high-stakes client pitch that required me to be “on” for twelve consecutive hours, I needed complete silence to recover. That withdrawal wasn’t a warning sign. It was survival.

But six months later, I found myself behind that same closed door for entirely different reasons. The silence wasn’t restoring me anymore. It felt like drowning in fog. I couldn’t pinpoint when the healthy need for solitude had morphed into something darker, when recharging had become hiding from a life that felt impossibly heavy.

Distinguishing between an introvert’s legitimate need for withdrawal and clinical depression remains one of the most confusing challenges introverts face. Both involve pulling away from social engagement. Both can look identical from the outside. Yet one represents healthy self-care while the other signals a serious mental health condition requiring professional support. Understanding the difference can quite literally change your life.

The Introvert’s Need for Solitude: A Biological Reality

Before examining depression, we need to establish what healthy introvert withdrawal actually looks like. As someone wired for depth and internal reflection, I process emotion and information through layers of observation and subtle interpretation. My mind notices details others overlook, from small shifts in tone to the emotional atmosphere filling a room. These impressions accumulate internally, creating a rich inner landscape that demands processing time.

Research from PLOS One distinguishes between self-determined motivation for solitude, which involves seeking time alone for genuine enjoyment and meaningful benefits, and preference for solitude regardless of reasons. Contrary to popular belief that introverts spend time alone simply because they enjoy it, the study found that dispositional autonomy rather than introversion itself predicts healthy motivation for solitary time. This matters because it suggests that quality of alone time trumps quantity.

During my years running creative teams in advertising, I learned to recognize when my social battery had depleted versus when something deeper was happening. After intense brainstorming sessions or client presentations, I craved silence the way a marathon runner craves water. That craving felt restorative, purposeful, even pleasurable. I anticipated the quiet with something approaching excitement.

Psychology Today describes this phenomenon clearly: introverts seek out and enjoy opportunities for reflection and solitude because they think better by themselves. The key word there is “enjoy.” When withdrawal feels like returning home after a long trip, when solitude brings relief and clarity rather than numbness, you’re witnessing healthy introvert functioning.

What Healthy Withdrawal Feels Like

Consider your last social event. Maybe you attended a dinner party that lasted four hours. You engaged meaningfully with conversations, contributed your perspectives, and genuinely connected with several people. But by the end, you felt that familiar fog rolling in, your mind slowing down, your capacity for additional interaction depleted.

Healthy introvert withdrawal following such an event carries specific characteristics. You feel tired but not hollow. Your thoughts remain accessible even if you lack energy to voice them. You anticipate recovery, understanding that solitude will restore you. Most importantly, you still care about things, even if caring about them right now feels like too much effort.

Working with diverse personality types throughout my corporate career taught me to recognize these patterns in myself and others. The introverts on my teams would disappear into their offices after big meetings, but they’d emerge hours later with brilliant ideas refined during that quiet time. Their withdrawal served a function: it enabled deeper work that wouldn’t have been possible amid constant interaction.

The Therapy Group of DC explains that social interactions require significantly more mental energy from introverts because they process information deeply and may feel overwhelmed by prolonged social exposure. This increased cognitive load leads to quicker exhaustion and a stronger need for solitude to recharge. The mechanism is physiological, not pathological.

The Crucial Distinction: Pleasure and Purpose

Here’s where the line between healthy withdrawal and depression becomes critical. Cleveland Clinic defines anhedonia as the inability to experience joy or pleasure, describing it as feeling numb or less interested in things once enjoyed. This symptom appears in roughly 70% of people with major depressive disorder and serves as one of depression’s most telling indicators.

When I retreated to my office after that twelve-hour pitch, I genuinely enjoyed the silence. I savored my coffee. I found pleasure in organizing my thoughts without interruption. The solitude felt like a gift I was giving myself. Six months later, when depression had taken hold, that same office felt like a prison. Coffee tasted like nothing. I wasn’t organizing thoughts so much as avoiding the exhausting prospect of having any.

The difference wasn’t about wanting to be alone. Both states involved wanting to be alone. The difference was about what happened during that aloneness. Healthy introvert withdrawal involves engaged solitude where you pursue activities that interest you, process experiences, and emerge restored. Depressive withdrawal involves empty isolation where time passes without purpose and nothing, including the solitude itself, brings satisfaction.

My experience managing creative professionals showed me how easily one can slide into the other. A copywriter I worked with would regularly take “think days” where she worked from home in complete silence. Those days produced her best work. But when her think days stretched into weeks, when the quality of her output dropped despite the extended solitude, I recognized something had shifted. She wasn’t recharging anymore. She was hiding.

Red Flags That Distinguish Depression from Introvert Withdrawal

According to the National Institutes of Health’s StatPearls resource, major depressive disorder diagnosis requires five or more symptoms persisting for at least two weeks, with at least one symptom being either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure. The symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Pay attention if your withdrawal includes these warning signs:

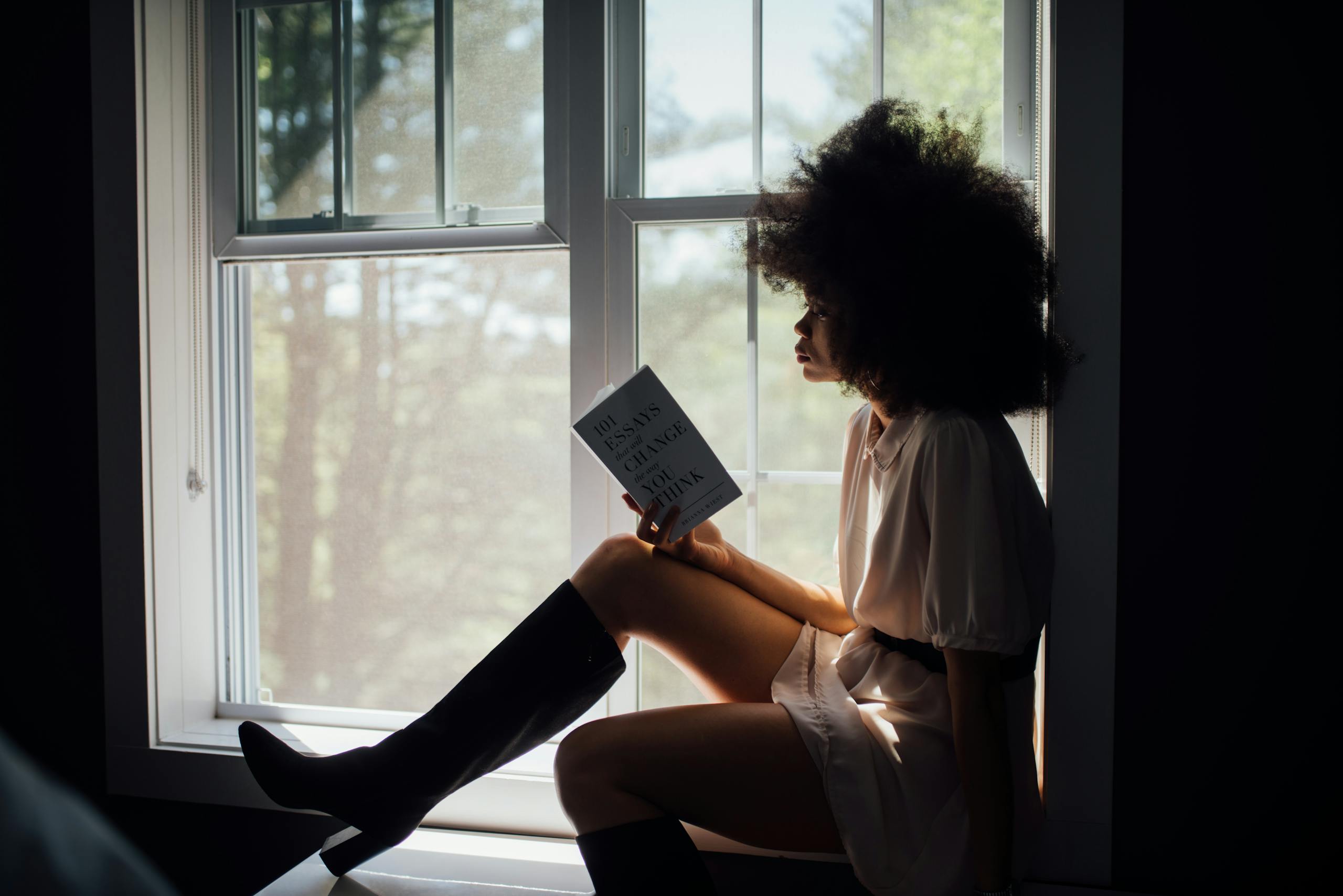

Loss of pleasure in previously enjoyed activities. Healthy introvert withdrawal involves retreating to do things you enjoy, whether reading, crafting, gaming, or simply thinking. Depressive withdrawal involves doing nothing because nothing sounds good. You might find yourself staring at a book you can’t focus on or scrolling through streaming services unable to choose anything because interest itself has evaporated.

Changes in sleep patterns. After social exertion, introverts might sleep longer as part of recovery. But consistent insomnia or hypersomnia disconnected from social exhaustion signals something different. When I was depressed, I slept ten hours a night and still felt exhausted. The sleep wasn’t restorative because the exhaustion wasn’t physical.

Appetite changes. Reaching for comfort food after a draining day differs vastly from losing all interest in eating or suddenly eating compulsively without enjoyment. Both patterns can indicate depression, especially when they persist beyond immediate social recovery needs.

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt. Healthy introverts recognize their need for solitude as legitimate self-care. They don’t feel guilty about it. Depression, however, often brings crushing guilt about “not being social enough” combined with feelings of personal failure or worthlessness that extend far beyond social preferences.

The Duration and Pattern Question

Healthy introvert withdrawal follows predictable patterns tied to social exertion. You attend a networking event, you need a quiet evening. You host a dinner party, you need the next morning alone. The withdrawal matches the expenditure. You can often estimate recovery time based on how demanding the social situation was.

Depression doesn’t follow this logic. The withdrawal persists regardless of social demands. You might have had a completely uneventful week with minimal social interaction yet still feel unable to face anyone. The need to disappear becomes constant rather than reactive. It stops responding to rest.

In my corporate experience, I noticed this pattern with my own mental health and with colleagues. Energy management for introverts works somewhat like a bank account. Social interaction withdraws energy, solitude deposits it. You can roughly predict your balance based on recent transactions. When the math stops working, when withdrawals happen without corresponding deposits restoring the balance, something else is operating.

Research published in Translational Psychiatry notes that anhedonia in depression is associated with more severe depressive episodes, increased suicidality risk, and poorer response to standard treatments. This makes early recognition crucial. The longer depression persists without intervention, the more difficult recovery becomes.

Asking Yourself the Hard Questions

When you find yourself withdrawing, try asking these questions honestly:

Am I looking forward to my alone time, or am I dreading everything equally? Healthy withdrawal involves anticipation, even eagerness, for solitude. Depressive withdrawal involves a flat emotional landscape where nothing, including being alone, feels appealing.

When I’m alone, do I engage with activities or just pass time? Journaling, reading, creating, thinking productively, all of these represent engaged solitude. Scrolling mindlessly, sleeping excessively, or staring at walls while hours disappear suggests something else.

Do I feel restored after my alone time, or does it feel like nothing changes? Recovery should be perceptible. After adequate solitude, healthy introverts feel their capacity returning. They can imagine socializing again, even if not immediately. If extended isolation leaves you feeling exactly as depleted as when it started, that’s concerning.

Has my need for solitude increased dramatically without corresponding increases in social demand? Needing more withdrawal than usual despite similar social schedules warrants attention. Your baseline isn’t broken, something is actively draining your energy.

Am I avoiding specific things or avoiding everything? Healthy introverts might skip a party to protect their energy for an important meeting. Depressive withdrawal involves avoiding the party, the meeting, the phone calls, the emails, and increasingly, basic self-care.

My Own Reckoning

Recognizing depression in myself took longer than it should have precisely because I’m an introvert. I could rationalize endless withdrawal as normal introvert behavior. “I’m just tired.” “I need more recovery time than most people.” “Creative work requires extended focus.” Every excuse contained a grain of truth that obscured the larger pattern.

What finally broke through my denial was noticing that solitude itself had stopped working. In healthy times, meditation centered me. Reading transported me. Quiet mornings with coffee felt sacred. Suddenly, none of these beloved activities penetrated the numbness. I was going through motions that produced nothing. That’s when I understood this wasn’t introversion. This was something else entirely.

Getting help required accepting that my introvert identity didn’t make me immune to depression. If anything, it made detection harder because withdrawal was already part of my behavioral repertoire. Friends and family couldn’t easily distinguish my “normal” solitude from “concerning” isolation because both looked similar from outside.

When to Seek Professional Help

The MSD Manual for healthcare professionals emphasizes that depressive disorders markedly impair the ability to function at work and interact socially, with significant suicide risk. Severity is determined by the degree of pain and disability, whether physical, social, or occupational, along with duration of symptoms.

Consider seeking professional evaluation if withdrawal persists beyond two weeks regardless of social demands, if you’ve lost interest in activities that previously brought genuine pleasure, if sleep or appetite changes significantly outside of normal recovery patterns, if you experience persistent hopelessness or worthlessness feelings, if concentrating or making decisions becomes difficult beyond typical introvert processing time, or if you have any thoughts of self-harm or suicide.

The stakes are too high for guessing. Depression is highly treatable, but only when recognized and addressed. Using introvert identity to avoid seeking help serves nobody, least of all yourself.

Supporting Healthy Withdrawal While Staying Vigilant

Understanding the distinction between healthy introvert withdrawal and depression doesn’t mean becoming hypervigilant about every quiet afternoon. Introverts need solitude. That need is legitimate, valuable, and should be honored rather than pathologized. What matters isn’t preventing withdrawal but ensuring it serves its intended purpose.

Build recovery time into your schedule proactively rather than reactively. Knowing you have designated quiet time coming can help you engage more fully during necessary social interactions. Track the correlation between social exertion and recovery needs so you understand your personal patterns. This baseline becomes invaluable if those patterns ever shift.

Notice the quality of your solitude, not just the quantity. Are you using alone time to pursue interests, process experiences, and engage with yourself? Or has alone time become empty time you’re simply enduring? The distinction matters enormously.

Consider keeping a mood journal, even briefly. Digital tools can help track patterns you might otherwise miss. Note not just when you withdraw but how withdrawal affects you. Does restoration occur? Does pleasure remain accessible? Changes in these patterns warrant attention.

Stay connected enough to have reality checks available. This doesn’t mean forcing constant socialization. It means maintaining at least one or two relationships where someone who knows you can honestly reflect whether your withdrawal seems proportionate and healthy. Sometimes outside perspective catches what self-analysis misses.

The Permission You Already Have

You’re allowed to need solitude. You’re allowed to decline social invitations without explanation. You’re allowed to structure your life around energy preservation rather than constant availability. Being an introvert isn’t a disorder requiring treatment or a limitation requiring management. It’s a temperament that carries genuine strengths when honored appropriately.

You’re also allowed to struggle. You’re allowed to experience depression even if you’ve always considered yourself mentally healthy. You’re allowed to need help even if admitting it feels like betraying your self-sufficient introvert identity. Mental health conditions don’t discriminate based on personality type. Seeking support isn’t weakness. It’s the same self-awareness that helps you recognize your introvert needs in the first place.

That Tuesday when my assistant found me behind a closed door wasn’t a crisis. But six months later, when I finally admitted to myself that the closed door had become a cage, asking for help was the bravest thing I did that year. The solitude I recovered after treatment felt different. It felt like coming home again rather than running away. That’s the difference worth protecting.

Trust yourself to know when withdrawal serves you and when it signals something requiring attention. You’ve spent a lifetime learning your own patterns. Honor that knowledge while remaining open to the possibility that patterns can shift. Sometimes disappearing is exactly what you need. Sometimes it’s a sign you need something else entirely. Only you can feel the difference from inside your own experience. Pay attention to what that experience is telling you.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should introvert recovery take after social events?

Recovery time varies by individual and the intensity of social engagement. Generally, proportionality serves as a guide: a brief social interaction might require a quiet evening, while an all-day conference might need a full recovery day. If your recovery time has dramatically increased without corresponding increases in social demand, or if recovery never fully occurs regardless of time spent alone, this warrants attention.

Can introverts experience depression differently than extroverts?

While depression symptoms remain consistent across personality types, introverts may find detection more challenging because withdrawal already features in their normal behavioral patterns. Extroverts who suddenly isolate raise immediate concern among friends and family. Introverts who isolate may appear to be behaving normally, making self-assessment and honest communication with trusted others especially important.

What’s the single most important distinction between healthy withdrawal and depression?

Pleasure and restoration. Healthy introvert withdrawal involves enjoying solitude and emerging restored. Depressive withdrawal involves empty isolation where neither the solitude nor anything else brings satisfaction, and time spent alone fails to replenish depleted energy regardless of duration.

Should introverts force themselves to socialize if they suspect depression?

Forced socialization isn’t the answer, but complete isolation typically worsens depression. Professional guidance helps determine appropriate balance. Sometimes gentle connection in comfortable settings with trusted people provides support without overwhelming an already depleted system. A therapist can help calibrate what’s helpful versus harmful for your specific situation.

Can tools and products help introverts monitor their mental health?

Sleep quality tools and mood tracking apps can provide objective data about patterns you might otherwise miss. Journaling systems help document the quality of your solitude over time. While these tools don’t replace professional assessment, they can alert you to shifts in patterns that warrant further attention and provide valuable information to share with healthcare providers.

Explore more Introvert Tools & Products resources in our complete Introvert Tools & Products Hub.

About the Author

Keith Lacy is an introvert who’s learned to embrace his true self later in life. With a background in marketing and a successful career in media and advertising, Keith has worked with some of the world’s biggest brands. As a senior leader in the industry, he has built a wealth of knowledge in marketing strategy. Now, he’s on a mission to educate both introverts and extroverts about the power of introversion and how understanding this personality trait can unlock new levels of productivity, self-awareness, and success.